Value for Money metrics report – Annex to 2019 Global accounts

Updated 24 January 2020

Applies to England

Contents

- Executive summary

- Introduction

- Providers’ reporting in the 2019 accounts - key themes

- Regulatory approach

- Value for Money performance - sector analysis/Key themes from analysis

- Sub-Sector analysis - Providers of supported housing and housing for older people/London-based providers/Large scale voluntary transfers less than 12 years old/Size of providers

- Annex A: Summary of Value for Money metrics and methodology

1. Executive summary

1.1 The Value for Money Standard (the Standard) seeks to ensure that boards of registered providers are optimising use of their assets and their resources and that they can demonstrate to stakeholders their approach to achieving and improving value for money in the delivery of their objectives. A key aim of the Standard is to support improved effectiveness and efficiency across the sector through enhanced transparency and accountability.

1.2 The regulator has defined a suite of standard metrics in the VfM metrics technical note and publishes this information annually so that boards and providers’ stakeholders can assess performance on these metrics and see how individual providers compare to other organisations.

1.3 The analysis for 2019 has shown the following at a sector level:

- Performance has been broadly stable over the last three years.

- Operating efficiency indicators fell slightly. The overall operating margin and the Return on capital employed (ROCE) fell by 5.6% and 0.6% respectively. Meanwhile the Headline social housing cost (HSHC), has increased by 12.4% to £3,690 per unit (median) since 2017. The falling margins largely reflect increasing reinvestment in existing stock across the country, and lower receipts from first tranche sales in London and the South East, combined with the ongoing rent reductions.

- There has been an increase in reinvestment in existing stock between 2017 and 2019, with providers across the cost distribution increasing their capital expenditure. • The average rate of new housing supply is consistent at around 1.5% of existing stock, with some notable variation by size, region and transfer status. • The analysis shows variations in performance reported by different types of registered providers. Particularly among smaller providers, these differences are increased by the characteristics of specialist care and support providers.

1.4 As in 2018, the quality of reporting, both on the metrics and the extent to which it met the Standard’s other requirements was mixed. The best reports presented a clear set of strategic objectives and suitable aligned, measurable targets. They reported historic performance against these targets and were honest about the reasons where targets were not achieved. Future targets and plans for achieving them were set out clearly, enabling understanding of what the provider was intending to achieve and how it would know if it had done it. Some included information enabling the reader to understand how investment and maintenance decisions were taken.

1.5 Weaker reporting included features such as:

- vague or generic objectives which did not clearly relate to the provider’s business plan or activities

- no targets, or targets that did not relate to the objectives

- no historic or intended future performance information, preventing understanding of whether progress was being made

- limited or non-specific information on investment plans and decision-making

- a lack of objectives and targets relating to key aspects of a social housing provider

- ignoring or failing to explain areas where performance did not meet target, and how performance would be improved

- no or unsuitable benchmarking, and adjustment of measures to create inconsistency.

1.6 In addition, we also identified cases where providers had adjusted information from year to year, for example by reclassifying homes between categories or adjusting cost allocations. If these are not supported by adequate explanation, they create a suspicion of manipulation to create “better” results. By masking year-on-year trends such adjustments can make it more difficult for both internal and external stakeholders to achieve a realistic view of a provider’s performance and thereby undermine efforts to improve it.

1.7 The regulator adopts a co-regulatory approach. In the value for money context this means that it seeks assurance from providers as to how they are meeting the requirements of the Standard in terms of decision making and strategic approach. Reporting can provide valuable additional assurance of how effective this is in practice, as well as making the sector more transparent and accountable to its tenants and other stakeholders.

2. Introduction

2.1 Registered providers are currently facing multiple competing pressures on their resources – ensuring that tenants are safe, and homes are of a suitable quality, increasing the supply of affordable homes, meeting more demanding environmental standards. In this context, value for money is not a nice-to-have or an add-on. It is fundamental to ensuring that scarce resources are used efficiently and effectively, decisions are made on a sound basis, and stakeholders understand how those decisions are made.

2.2 The regulator’s revised Value for Money Standard and supporting Code of Practice were introduced in 2018. The purpose of the Standard is to encourage providers to optimise the use of their assets and resources and improve the efficiency, economy and effectiveness with which they work towards their strategic objectives. The Standard does this by increasing the transparency and accountability of providers.

2.3 Providers who are meeting the Standard will set clear strategic objectives which relate to their business plan; have a clear approach to achieving value for money in working towards those objectives; and set and monitor progress against measurable targets for the objectives. Providers are independent organisations and the regulator does not seek to influence what their strategic objectives should be. However, the regulator does expect that providers should be able to define precisely what they are seeking to achieve and to objectively demonstrate whether they are achieving these objectives.

2.4 Providers are required to report publicly on historic performance against their targets and plans for the future – including areas where performance has not been up to expectations. In addition, the Standard requires providers to report performance on a defined suite of metrics defined by the regulator against a suitable peer group, to enable providers and stakeholders to compare providers on a consistent basis. These metrics, and their calculation, are summarised in Annex A.

2.5 The reporting expectations in the Standard are an opportunity for providers to demonstrate how they are delivering value for money in their activities. This is important for the provider, the wider sector and external stakeholders, including tenants, as it shows the provider’s commitment to making optimal use of its assets and resources – including those subsidised by the taxpayer. The regulator does not have a set format or right answer for this reporting and would encourage providers to use whichever format would best aid transparency in future. As long as the report captures all relevant requirements – including explaining how performance has fallen short - providers should not feel obliged to follow any one reporting model.

2.6 Similarly, the regulator does not have required benchmarks or targets for the standard metrics. Some of them work against each other, and no provider is likely to be in the “best” quartile on all measures. The expectation is that providers will engage with the metrics and present information which increases transparency and understanding.

2.7 In the first year that the Standard was in force, the regulator was mainly concerned with the calculation and reporting of the defined metrics. Since then, we have engaged with providers on the full range of requirements in the Standard and have reflected our findings in regulatory judgements. We have also reviewed reporting in this year’s accounts.

2.8 The remainder of this publication presents analysis of the standard metrics data suite and commentary on how providers addressed the other reporting requirements of the Standard. Value for money happens inside organisations, in their strategic approach and decision making – and in the questions that boards and executives ask of themselves.

2.9 Section 3 considers how providers have addressed the wider reporting requirements of the Standard, beyond the standard metrics, including definition of strategic objectives, and the setting and measurement of associated targets. Section 4 sets out our regulatory approach. Section 5 presents the aggregate metrics results for the whole sector, including the quartile distributions for each metric. Section 6 looks at the metric performance for sub-sector groups, following the explanatory factors identified in previous analysis of cost variation in the sector.

2.10 This analysis provides valuable information for providers and stakeholders to understand how an individual organisation’s performance compares with the sector as a whole and potentially with similar organisations.

3. Providers’ reporting in the 2019 accounts – key themes

3.1 This was the second year in which registered providers have been required to meet the reporting requirements of the 2018 Value for Money Standard. In the first year, given the limited time between the new Standard coming into force and deadlines for completion of accounts, the regulator took a proportionate view of providers’ responses and focussed mainly on the completion of the regulator’s defined metrics.

3.2 In 2019, providers have had well over a year to adapt to the requirements of the new Standard, and the regulator’s expectation is that providers should be able to meet all the Standard’s reporting requirements including the clear articulation of strategic objectives and measurement of performance against the provider’s own targets.

3.3 Overall the regulator’s assessment of reporting in the 2019 accounts demonstrates that registered providers have begun to embrace the reporting requirements of the Standard. Although this year’s reports were in general of higher quality compared to the reports looked at previously, only a small number of registered providers met all the reporting requirements. This section identifies key themes and issues emerging from our review of providers’ accounts to support effective value for money reporting in future.

3.4 The regulator has not prescribed how providers should reflect the reporting requirements of the Standard and does not want to discourage providers from developing innovative formats that would better aid transparency of their performance in future accounts. As long as the report captures all relevant requirements, providers should not feel obliged to follow any one reporting model.

3.5 In a move away from VfM self-assessments, the regulator requires boards to publish a brief report that would enable a range of stakeholders to assess their organisation’s performance against the delivery of their objectives. This includes how they have performed against their own targets and against the regulator’s metrics and being honest where performance needs to improve.

3.6 Reports that provided the most valuable assurance in relation to their organisation’s performance, published their strategic objectives and aligned them with a suite of relevant measures and targets. They also demonstrated how their organisation performed against each measure when compared to the previous year, the actual year target and provided forecast targets over the shorter term – this is the importance of the golden thread concept, which allows stakeholders to follow an organisation’s performance from one year to the next.

3.7 Our review this year had a focus on providers’ organisational strategies and their own targets. Some providers included considered objective measures and targets, reported performance against them and were honest where targets were not achieved. Reports that were less clear tended to have generic objectives meaning it is difficult to assess which targets related to their objectives or how the registered provider would know if they met their objectives. For example, some providers reported their performance using the Sector Scorecard measures, but without indicating to which, if any, of their strategic objectives each of these measures related, or what their target level of performance was. This lack of transparency made it difficult for stakeholders to assess a provider’s performance against its objectives.

3.8 A key element of the Standard requires registered providers to set out their strategy for providing homes that meet a range of needs. Some reports did this by including an overview of a registered provider’s investment strategy that enabled stakeholders to understand the rationale for investment decisions. For example, some reports assessed demand in the area of operation to explain expenditure on new supply or used stock condition data to justify the type of remedial investment required to existing housing stock. These were accompanied by quantified measures and targets, for example on maintenance or major repair costs per unit or new supply of social and non-social housing units. Other comprehensive reports aligned their strategic approach to asset management with related targets covering for example, fire and gas safety and Decent Homes compliance

3.9 On the other hand, some reports provided limited information on investment plans, omitting for example the type of new units forecast, the timeframe over which units would be delivered or whether specific development plans supported demand in the local area. Despite a general increased focus on reinvestment to existing stock, we noted that some registered providers omitted measures and targets relating to their current stock.

3.10 A significant minority of reports failed to address one of the Standard’s specific expectations; a clear appraisal of how well an organisation had performed against its own targets. Where outputs were published, they often did not explain whether this performance had met prior expectations or had fallen short of target. This provides limited assurance to stakeholders that objectives are being met or more importantly that the organisation’s performance is being challenged by the board themselves.

3.11 Benchmarking is a vital tool that can help drive improvement in the delivery of value for money. It can identify where changes are potentially needed, and it can also help to improve the efficiency of the organisation. In a drive to support comparative analysis, we have published the VfM metrics at both a sector and at a sub-sector level in order that providers have a mechanism with which to compare their organisation’s performance against peers with similar characteristics.

3.12 The Value for Money metrics Technical Regression Note, demonstrates that there are material differences in reported performance between different groups of providers showing the value of benchmarking with organisations that have similar business models or operating area. Those providers who do not undertake peer comparisons with organisations in a similar position, make it more difficult for boards and other stakeholders to make meaningful judgements about the performance of their organisation.

3.13 Our review of providers’ accounts showed that a limited number of providers are adjusting measures that are widely used amongst benchmarking clubs to compare their own performance against. In order to promote consistency, we would encourage providers who adjust common measures to explain the rationale for doing so. Registered providers are reminded that the value for money measures set out by the regulator must not be adjusted and should be reported on the precise basis set out in the technical note.

3.14 In 2018, we wrote to 34 providers who did not apply the regulator’s measures to calculate the metrics. In addition, we also contacted providers where data quality issues were identified when compiling the value for money data analysis. Despite improved reporting in this area, there is evidence that some providers continue to publish their Headline Social Housing Cost on an inconsistent basis. Most notably, this is often due to the movement of costs that relate to social housing activities and recognising those costs as non-social housing. We will continue to follow up data integrity issues with providers over the forthcoming year which can be reflected as part of a provider’s regulatory judgement.

3.15 Registered providers are reminded that the VfM Code of Practice amplifies the requirements of the Standard. Our analysis of value for money reporting suggests that few registered providers have made use of the range of reporting approaches that are outlined in the Code. From time to time it may be helpful to disclose the performance of activities; for example, reporting at a disaggregated level of the business, or where there may be measurable plans that are relevant to a merger or possibly where registered providers are investing in non-social housing activities. Reporting at a more granular level can enhance stakeholders’ understanding of the impact, social or otherwise, that an organisation has in their area of operation. Our review of several accounts indicates that there is anecdotal evidence to suggest that some of this detail may be reported elsewhere.

3.16 Boards have a duty to balance economic and political risks when setting their strategic objectives to ensure the long-term viability of their organisations. Changes in the operating environment and to the economy can impact registered providers’ performance, which means that from time to time they are unable to meet their desired outcomes. Some providers did explain why targets could not be met. For example, registered providers undertaking planned development programmes in London and the South East were unable to meet their development targets due to a slowdown in market sales and this has been made transparent in the accounts we reviewed.

3.17 Some registered providers limited their reportig on their actual performance only and did not provide performance targets meaning it is difficult to determine whether the organisation had met their targets. It may be uncomfortable for boards to report on activities or services that are not performing as well as they had intended. However, transparency on this matter is a requirement of the standard and open reporting provides the regulator with assurance that the board has recognised and is tackling areas of underperformance.

4. Regulatory approach

4.1 The RSH has always made clear that it is for boards to decide how they run their businesses and assure themselves that they are complying with the regulatory standards. It is important that boards should understand the range of factors that influence performance of their own organisation.

4.2 The demands on registered providers are increasing as the expectations from government and tenants rise. The regulator will continue to seek assurance that providers make the best use of their resources and their assets and have clear plans in place to make ongoing improvements to the value for money in their organisations.

4.3 The RSH will use the value for money metrics to identify cases which may indicate a lack of assurance on value for money performance. In such cases we may need to engage with registered providers to seek further assurance that the organisation is meeting the requirements of the Standard.

4.4 Registered providers must ensure that the reporting undertaken in future accounts meets all the reporting requirements of the Standard. Where we identify year-on-year performance reporting weaknesses, we will reflect this in our regulatory judgements.

5. Value for Money performance – Sector analysis [^5]

Table 1: Summary of sector trends (2017-2019) (Providers owning / managing more than 1,000 homes)

| VfM metric | Reinvestment | New supply social [^6] (%) | New supply (non-social) % | Gearing % | EBITDA MRI interest cover % | Headline social housing CPU £000 | Operating margin (social) % | Operating margin (overall) % | ROCE % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper quartile | 2019 | 8.7% | 2.5% | 0.13% | 53.9% | 238% | £4.69 | 34.6% | 30.8% | 4.7% |

| 2018 | 8.7% | 2.3% | 0.07% | 53.1% | 263% | £4.50 | 37.1% | 34.1% | 5.4% | |

| 2017 | 8.6% | 2.2% | 0.03% | 54.8% | 278% | £4.36 | 39.3% | 36.0% | 5.6% | |

| Median | 2019 | 6.2% | 1.5% | 0.00% | 43.4% | 184% | £3.69 | 29.2% | 25.8% | 3.8% |

| 2018 | 6.0% | 1.2% | 0.00% | 42.9% | 206% | £3.40 | 32.1% | 28.9% | 4.1% | |

| 2017 | 5.6% | 1.2% | 0.00% | 43.4% | 212% | £3.29 | 34.7% | 31.4% | 4.3% | |

| Lower quartile | 2019 | 4.2% | 0.6% | 0.00% | 32.6% | 139% | £3.18 | 23.1% | 20.0% | 3.0% |

| 2018 | 3.9% | 0.5% | 0.00% | 33.1% | 154% | £3.01 | 25.5% | 22.7% | 3.3% | |

| 2017 | 3.7% | 0.4% | 0.00% | 33.5% | 174% | £2.96 | 28.7% | 25.0% | 3.5% | |

| Weighted average | 2019 | 6.4% | 1.7% | 0.31% | 46.7% | 153% | £4.12 | 30.5% | 25.0% | 3.6% |

| 2018 | 6.2% | 1.5% | 0.23% | 45.8% | 174% | £3.92 | 32.8% | 27.6% | 4.0% | |

| 2017 | 7.3% [^7] | 1.5% | 0.22% | 45.8% | 169% | £3.78 | 34.3% | 29.7% | 4.3% |

Key themes from analysis

5.1 Table 1 shows the distribution of performance across the sector over the past three years. It is possible to identify several broad trends across the metrics suite as a whole.

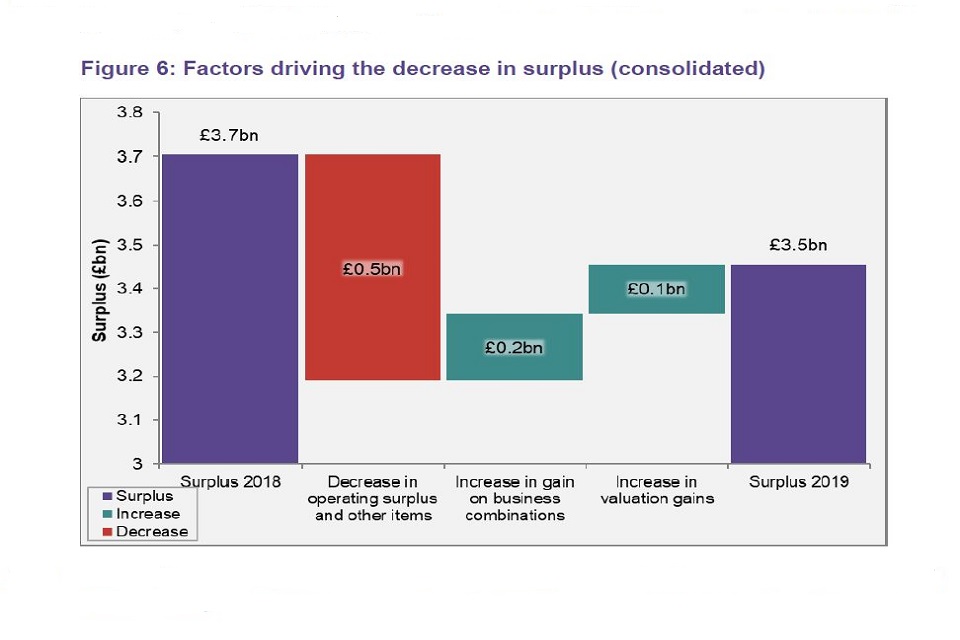

5.2 As the following analysis of individual metrics shows in more detail, headline social housing costs per unit have risen over the last three years; in part explained by increased expenditure on maintenance and major repairs. These rising costs, along with the ongoing rent cuts and more recently falling margins on sales, have contributed to falling operating margins, falling interest cover and return on capital employed.

5.3 Over the three years there has also been a slight increase in new social supply as a proportion of the existing stock. This, combined with rising investment in the existing stock, has led to an increase in the overall reinvestment rate.

5.4 It is striking that these trends are visible throughout most of the sector. The same pattern of rising costs, falling margins, and increased reinvestment is seen in the sector median and in both the upper and lower quartile of performance on each metric. Individual providers have implemented a wide range of VfM strategies and have sought to make differing levels of cost efficiencies since the introduction of the rent cuts in 2016. However, at a sector level the impact of these business level decisions has been outweighed by the impact of widespread changes in the sector’s operating environment, particularly the near universal application of the rent cuts.

5.5 This means that there is limited evidence of any material change in the distribution of performance across the sector. In proportionate terms, there has been little change in the distribution of performance as measured by the interquartile range on most of the measures. The gap between the providers with the highest and lowest costs has neither significantly narrowed nor widened over the last three years and the gap between those with the largest and smallest margins has slightly widened.

5.6 The one exception to this picture is on reinvestment where the interquartile range has narrowed over the past three years with reinvestment amongst the lower quartile rising more quickly than in the upper quartile. However, across the metrics suite there is limited evidence that the range of performance is either narrowing or widening. The range of reported performance on the metrics across the sector remains extremely wide.

Reinvestment and new supply

5.7 Table 1 also shows that in the three years to 2019, sector performance has remained relatively consistent. The sector has continued to deliver a significant number of new affordable homes for rent and market sale. The delivery of new social homes as a percentage of total stock owned has increased from 1.2% to 1.5% since 2017. Median reinvestment [^8] (which includes both investment in the existing stock and new supply), has increased from 5.6% to 6.2% over the same period.

5.8 There continues to be variance in new supply delivery, with the lower quartile delivering homes equivalent to only 0.6% of their existing stock in 2019 compared to 2.5% for the upper quartile. Providers in the lower quartile tend to generate lower operating margins, often from supported housing, and are therefore less able to invest in new supply.

5.9 There is a minority of registered providers who deliver a modest level of new supply (social). These tend to be registered providers with significant supported housing or housing for older people stock and who typically have higher costs and lower operating margins from which they can invest in new units. Equally, large-scale voluntary transfer organisations, in particular organisations that are still in their first five years after transfer, tend to focus exclusively on investment in their existing stock to ensure they meet their transfer commitments.

5.10 The development of new supply (social) as a proportion of existing stock varies considerably across England. The highest levels of development are delivered by providers based in the East of England [^9] and East Midlands. The average median new supply (social) is 2.5% and 2.3% respectively.

5.11 Registered providers in the North East and North West of England deliver the lowest levels of new supply (social). The median level of development for each region is 0.6% and 0.7% respectively, compared to the sector median of 1.5%. A possible explanation for this is that house prices in these regions tend to be more affordable [^10] and therefore demand is likely to be lower compared to the rest of England.

5.12 There is a noticeable gap between the median level of new supply (social) as a proportion of existing stock for registered providers based in London, which is 1.4%, and the weighted average level of new supply stock of 1.9%. This indicates that larger registered providers based in London are developing at a faster rate compared to their smaller counterparts who are also based in London. This may also mean that higher land and labour costs are precluding smaller London-based providers from delivering new units.#

Table 2: Social housing supply by region of operation

| Region of operation | New supply (social) units | Total social units owned | Total supply (social %) - median | New supply (social %) - weighted average |

| East Midlands | 1,766 | 73,346 | 2.3% | 2.4% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| East of England | 4,370 | 178,810 | 2.5% | 2.4% |

| London | 6,116 | 323,751 | 1.4% | 1.9% |

| Mixed | 12,228 | 752,274 | 1.5% | 1.6% |

| North East | 1,274 | 153,651 | 0.6% | 0.8% |

| North West | 3,765 | 468,126 | 0.7% | 0.8% |

| South East | 6,043 | 278,351 | 2.2% | 2.2% |

| South West | 3,734 | 172,519 | 1.9% | 2.2% |

| West Midlands | 4,978 | 229,374 | 1.9% | 2.2% |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 2,187 | 158,845 | 1.4% | 1.4% |

| England | 46,461 | 2,789,047 | 1.5% | 1.7% |

5.13 New supply (non-social) only includes development on the provider’s balance sheet and excludes units developed by joint ventures. Since most non-social development is undertaken in joint ventures there is minimal difference between quartiles. Given the comparatively limited level of non-social supply reported in registered vehicles, we have not broken this down by region.

5.14 Over the past three years the level of reinvestment in the sector has grown. Overall, investment in development remains the largest contributor to the reinvestment rate. However, as noted above, the level of reinvestment by the lower quartile of providers has grown most rapidly and this metric shows a narrowing of performance between quartiles, even though there is still a wide gap between the levels of new supply delivered across the sector. Over the past year increased investment in works to the existing stock has been the main driver in year-on-year change in the reinvestment metric.

Table 3: Sector level reinvestment broken down by investment type

| Sector | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reinvestment | Reinvestment (weighted average) | Works to existing [^11] (weighted average) | Development and other [^12] (weighted average | |

| 2018 | 6.03% | 6.18% | 1.16% | 5.02% |

| 2019 | 6.24% | 6.45% | 1.34% | 5.11% |

| % change | 3.5% | 4.5% | 16.1% | 1.8% |

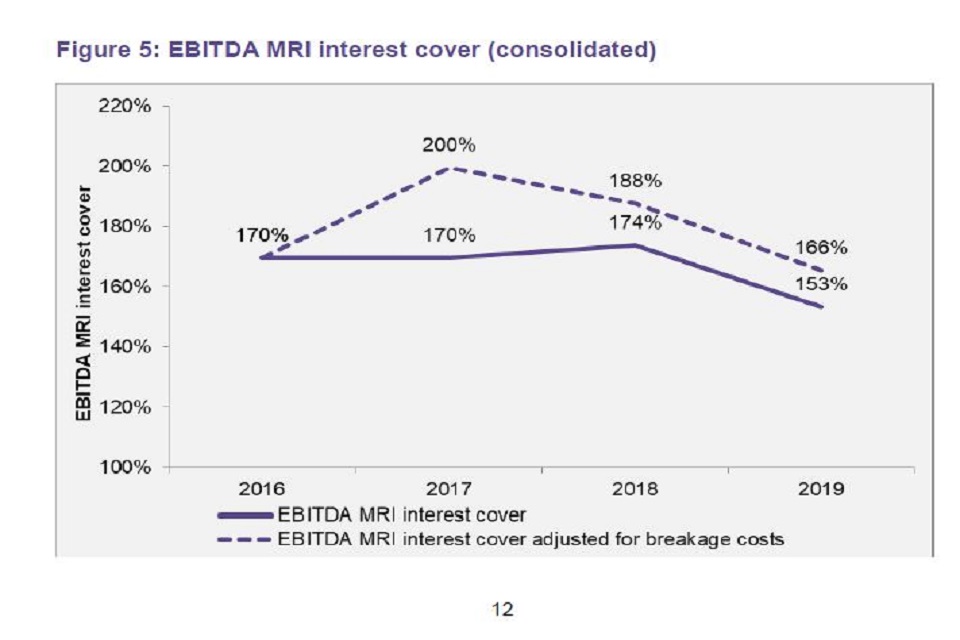

5.15 Table 3 shows that the weighted average sector figures for works to existing units increased by 16.1% between 2018 and 2019. This compared to the development and acquisition of new supply which increased by 1.8%. The increase to works to existing housing stock accounted for 67% of the total increase seen in the reinvestment metric (weighted average) over the same period.

Debt based metrics

5.16 Over the past three years, the weighted average EBITDA MRI interest cover fell by 16%, as shown in Table 1, due to increasing debt levels and the reduction in operating margin. Despite the fall in the EBITDA MRI interest cover, overall the financial capacity in the sector remains strong. There was consistent movement across the distribution: median interest cover remains strong at 184% though lower than the 212% reported in 2017. Registered providers in the lower quartile reported interest cover of 139% while providers in the upper quartile remain strong with an interest cover of 238% in 2019.

5.17 As shown in Table 1, due to increasing debt levels and the reduction in operating margin. Despite the fall in the EBITDA MRI interest cover, overall the financial capacity in the sector remains strong. There was consistent movement across the distribution: median interest cover remains strong at 184% though lower than the 212% reported in 2017. Registered providers in the lower quartile reported interest cover of 139% while providers in the upper quartile remain strong with an interest cover of 238% in 2019.

5.18 The gearing metric assesses how much debt a provider holds as a percentage of their assets and highlights the degree of dependence on debt finance; it can be restricted by registered provider’s lender’s covenants. As shown in Table 1, the distribution of gearing has held constant over the past two years with the median at around 43%. Typical providers in the lower quartile include small specialised organisations, while the most active developers and recent stock transfers are concentrated in the upper quartile.

Headline social housing cost per unit

Table 4: Sector level headline social housing cost per unit by cost type

| Weighted average | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 18-19 % change | 17-19 % change | |

| Management | £1,045 | £1,016 | £967 | 2.9% | 8.2% |

| Service charges | £626 | £599 | £560 | 4.6% | 11.8% |

| Maintenance and major repairs | £1,965 | £1,828 | £1,787 | 7.5% | 10.0% |

| Other | £481 | £477 | £466 | 0.8% | 3.3% |

| HSHC | £4,118 | £3,919 | £3,779 | 5.1% | 9.0% |

5.19 Table 1, the distribution of gearing has held constant over the past two years with the median at around 43%. Typical providers in the lower quartile include small specialised organisations, while the most active developers and recent stock transfers are concentrated in the upper quartile.

5.20 Table 4 shows that the sector’s cost per unit has increased by 9.0% over the past three years. This is significantly ahead of general CPI inflation in the economy as a whole, with the difference influenced by factors specific to the sector. The increase has been driven by rising maintenance and major repairs expenditure which has grown by 10.0% since 2017, with 7.5% of that increase occurring between 2018 and 2019.

5.21 Our analysis shows that the HSHC (weighted average) has increased by £199 per unit since 2018 of which 69% (£137) relates to maintenance or major repairs expenditure.

5.22 Management costs per unit also increased by 8.2% over the period 2017-2019 This is likely to be influenced by upward pressure on wages. Unemployment rates remained at 3.8% between August and October 2019, [^13] close to a 45-year low. This has helped support an increase in real wages. The UK average total weekly earnings increased by 3.6% compared to 2018 (not adjusted for price inflation), and by 1.8% in real terms (after adjusting for inflation). For those organisations with a significant number of staff at or near the minimum wage, real costs of labour are likely to have risen by a higher proportion following the introduction of the new Living Wage rate (which is 4.9% higher compared to 2018).

5.23 Movements in headline unit costs were concentrated in the middle of the distribution. The median increased by £400 per unit from £3,290 in 2017 to £3,690 per unit in 2019, while the lower quartile increased from £2,960 in 2017 to £3,180 in 2019, and the upper quartile increased from £4,360 to £4,690 over the same period.

5.24 The scatter graph at Figure 1 shows that there remains a considerable level of variation in the headline social housing costs across the sector. The mean [^14] headline social housing cost per unit is £4,120. This compares to the median average cost per unit which is £3,690 and is denoted by the red line. The difference between the median and the mean is driven by registered providers with high levels of supported housing (2019 median: £8,460), housing for older people (2019 median: £6,150) and London-based registered providers (2019 median: £6,070).

5.25 Some of the variability in cost across the sector can be explained by measurable provider characteristics, such as location and specialism. These are explored further in section 2 on sub-sector analysis. However, the regulator’s regression analysis has repeatedly shown that not all this variation can be explained by measurable factors. Part of the unexplained variation is likely to be due to the availability of data (for example on stock condition) but part will be due to differences in operating efficiency between different organisations.

Figure 1: HSHC per unit by total social stock owned and/or managed [^15]

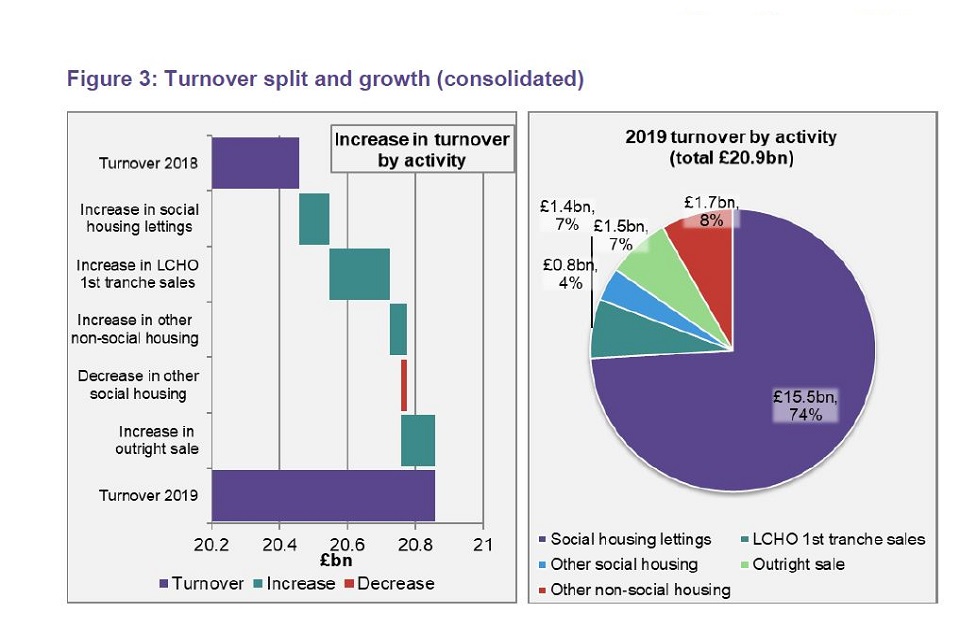

Figure 3: Turnover split and growth (consolidated)

Efficiency-based metrics

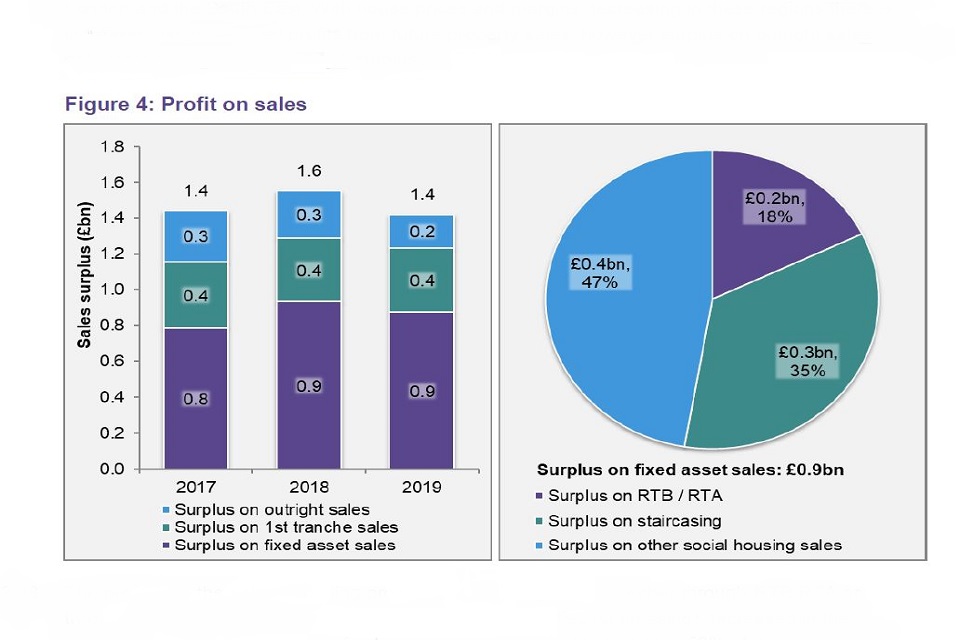

5.26 The operating margin (overall), and the operating margin (social housing lettings), have reduced across the distribution due to higher maintenance and major repairs expenditure, social rent reductions and reducing sales profits. The operating margin (social housing lettings), is higher than the operating margin (overall), across all quartiles, as the margins on many non-social housing activities are lower than those for the core lettings business. This reinforces the need for clear decision-making in providers, when allocating resources between different types of housing.

5.27 The return on capital employed assesses the degree of efficient investment of capital resources and compares the operating surplus to total asset values. The reduction in operating margin caused a reduction in ROCE across the distribution, with the largest movement in the upper quartile. At a sector level, the median ROCE fell from 4.1% in 2018 to 3.8% in 2019. The upper quartile also fell from 5.4% in 2018 to 4.7% in 2019. This reflects the fact that there are many London-based organisations in this quartile which have seen both falling profits from shared ownership sales and a rise in their total asset value. London based providers saw a 6.2% increase in asset values which is above the sector wide increase in asset valuations of 4.7.

6. Sub-sector analysis

Table 5: Summary of sub-sector metrics (Registered providers (RPs) owning/managing more than 1,000 homes) [^16]

| Quartile data | No of RPs | % of sector (social units owned) | Reinvestment % | New supply (social) % | New supply (non-social) % | Greaing % | EBITDA MRI interest cover % | Headline social housing cost per unit £000 | Operating margin (social) % | Operating margin (overall) % | ROCE % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All returns | Upper quartile | 8.7% | 2.5% | 0.13% | 53.9% | 238% | £4.69 | 34.6% | 30.8% | 4.7% | ||

| Median | 217 | 100.0% | 6.2% | 1.5% | 0.00% | 43.4% | 184% | £3.69 | 29.2% | 25.8% | 3.8% | |

| Lower quartile | 6.2% | 1.5% | 0.00% | 43.4% | 184% | £3.69 | 29.2% | 25.8% | 3.8% | |||

| Provider sub-set | Median | |||||||||||

| Size (social units owned | >30,000 | 25 | 44.5% | 6.3% | 1.8% | 0.26% | 45.4% | 159% | £3.88 | 32.8% | 25.8% | 3.7% |

| 20,000-29,000 | 14 | 13.3% | 5.5% | 1.5% | 0.16% | 46.8% | 171%, | £3.38 | 29.9% | 27.4% | 3.6% | |

| 10,000-19,999 | 37 | 19.6% | 6.8% | 1.5% | 0.01% | 47.1% | 158% | £3.52 | 28.7% | 25.2% | 4.0% | |

| 5,000-9,999 | 55 | 14.4% | 6.9% | 1.4% | 0.00% | 46.3% | 203% | £3.55 | 29.7% | 28.5% | 4.1% | |

| 2,500-4,999 | 38 | 5.4% | 6.7% | 1.9% | 0.00% | 43.4% | 194% | £3.82 | 29.8% | 25.7% | 3.6% | |

| < 2,500 | 48 | 2.7% | 4.3% | 0.6% | 0.00% | 34.1% | 194% | £4.88 | 23.3% | 20.3% | 3.1% | |

| cost factor | LSVT <12yrs [^17] | 17 | 7.3% | 14.1% | 0.6% | 0.00% | 28.3% | 151% \ £4.11 | 26.5% | 25.3% | 4.7% | |

| London [^18] | 28 | 11.2% | 4.8% | 1.4% | 0.00% | 38.1% | 159% | £6.07 | 26.3% | 22.7% | 2.8% | |

| SH provider [^19] | 17 | 1.5% | 4.2% | 0.8% | 0.00% | 13.3% | 228% | £8.46 | 12.9% | 8.0% | 3.4% | |

| HOP provider [^20] | 7 | 3.1% | 4.9% | 0.0% | 0.00% | 33.9% | 172% | £6.15 | 20.6% | 19.2% | 3.4% |

6.1 Table 5 demonstrates that the reported performance on the VfM metrics differs significantly according to the characteristics of the organisations. There are still widespread variations within each of the groups identified, but there are also consistent patterns according to the nature of each provider’s business, their geographical location and size. Supported housing providers, organisations based in London and early years transfer organisations all have distinctive common characteristics. The influence of size on reported performance is more complex, but some size bands show material divergence from sector averages.

6.2 Figures, 2, 3 and 4 below illustrate the range of performance for these different groups for three of the metrics: reinvestment, housing supply (social) and headline social housing cost per unit.

Figure 2: Reinvestment by cost factor and size [^21]

Figure 4: Profit on sales

Figure 3: New supply (social) medians by cost factor and size

Figure 5: EBITDA MRI interest cover (consolidated)

Figure 4: Headline social housing cost per unit medians by cost factor and size

Figure 6: Factors driving the decrease in surplus (consolidated)

6.3 The differences in reported performance between different sub-sectors demonstrates the importance of ensuring that benchmarking is undertaken using a comparable peer group. The rest of this section draws out some the key differences in performance between different groups of providers.

Providers of supported housing and housing for older people

6.4 Registered providers whose primary activity is the provision of supported housing and housing for older people account for 11% of all registered providers, with more than 1,000 units. As a group, supported housing providers have significantly higher costs and lower overall operating margins compared to the rest of the sector meaning that they have more limited financial capacity with which to service debt for development. In consequence, their level of gearing is much lower than the sector median, whilst social housing supply and overall reinvestment rates are lower.

6.5 Similar patterns hold for those providers with significant levels of housing for older people, albeit to a less exaggerated extent than for supported housing specialists. Although their costs remain higher than the sector median, housing for older people providers tend to have lower costs and stronger margins than the supported housing providers. This translates into greater ability to access debt, and consequently higher levels of reinvestment and new supply than their supported housing counterparts.

6.6 These patterns have, if anything, strengthened over the past year. Median unit cost for supported housing providers has fallen year on year, although this is in part explained by reclassification of some providers leading to change in the composition of the two groups. A key driver that explains the 9.7% increase in the housing for older people median unit cost and the 5.3% decrease in the supported housing median between 2018 and 2019 is the reclassification of a specialist provider from housing for older people to supported housing. The delivery of new supply by supported housing providers has fallen from 0.9% to 0.8% and by 0.2% for housing for older people providers since 2018.

London-based providers

6.7 While registered providers based in the capital generate higher rates of rental income compared to the rest of England, they are more likely to incur higher overhead costs. This means they tend to have higher unit costs and lower operating margins. The weighted average unit cost is 51% higher compared to the weighted average of £4,120 per unit for England and 69% higher compared to the south east – the second most expensive region in England.

6.8 The weighted average cost per unit for London-based registered providers is £6,200, an increase of 9.1% from 2018 when the weighted average was £5,680. The profile of this group has changed over the past three years which has had an impact on the average cost base. This includes the addition of a specialist lease-based registered provider with a very high cost base, which has crossed the 1,000 unit threshold and submitted a Financial Viability Assessment for the first time, and the impact of two mergers. However, even when we controlled for these changes, the annual increase between 2018 and 2019 was 7.8%.

6.9 The vast majority of this increase has been driven by increased maintenance and major repairs expenditure from £2,280 per unit in 2018 to £2,780 in 2019. In absolute terms, London-based registered providers invest more in both existing stock and new development, compared to registered providers in the rest of the country. However, their median reinvestment level as a percentage of the value of the existing stock is lower due to significantly higher property values in the capital.

6.10 Registered providers that are based in London have the largest gap between the region’s median level of new supply (social), and the region’s weighted average level of new supply (social). The median level of new supply (social) for London-based providers increased from 1.0% in 2018 to 1.4% in 2019, while the weighted average delivery of new supply (social), also increased from 1.6% to 1.9% over the same period. This indicates that the largest registered providers based in London are developing at a faster rate compared to smaller providers in the same region.

Large scale voluntary transfers less than 12 years old

6.11 LSVT organisations in their first 12 years after transfer typically have higher reinvestment metrics compared to the rest of the sector due to significant works to existing properties agreed as part of their transfer agreements. These providers also have average property values that are significantly lower when compared to the rest of the sector at the time of transfer.

6.12 Consequently, LSVT organisations that are less than 12 years old tend to have higher unit costs compared to other types of organisations. Our analysis shows that 55% of an LSVT’s unit cost is attributable to maintenance and major repair expenditure compared to the sector average of 48%. The median cost of running an LSVT unit is £4,110 compared to the sector median of £3,690.

6.13 The reinvestment in new and existing stock by LSVT organisations has increased from 9.8% in 2018 to 14.1% in 2019. This is partly due to a change in the composition of the group. Since 2018, eight registered providers have moved out of this group as they are older than 12 years. However, there have also been increases in the level of investment by those providers that remain within this category. The large increase is also due to higher reinvestment in existing stock by nine of the remaining 16 registered providers in the group.

6.14 The new supply (social) units delivered by LSVT organisations fell by 0.2% in 2018 to 0.6% in 2019. However, this can also be explained by the reduced number of registered providers in this group over the same period. Some of the most mature providers that have moved out of this category had higher levels of supply than the more recent transfers that remain within the group.

6.15 The regulator’s previous analysis has shown that there are no statistically significant differences between older LSVTs (>12years since transfer) and traditional providers. We have therefore not identified this group separately.

Size of providers

6.16 There is no clear, unambiguous relationship between size of provider and reported performance on the metrics, once you control for other factors. Some of the size bands that we have identified in Table 5 do have distinctive characteristics, particularly the very largest providers (those with more than 30,000 properties) and the very smallest (those with fewer than 2,500 units). However, much of the difference can be explained by other factors rather than size per se, in particular, the amount of stock owned in London, and the prevalence of supported housing.

6.17 The largest registered providers (with more than 30,000 properties) have a median cost of £3,880 per unit compared to the sector median of £3,640 per unit. These registered providers own 24.4% of their stock in London, where the median cost per unit is 64% higher when compared to the sector median. This compares to registered providers with between 1,000 to 30,000 units, who have a median cost per unit of £3,680 – however only 10.2% of their stock is London-based.

6.18 At the other end of the size distribution, the smallest providers also have higher cost per unit than the sector median. However, over one quarter of registered providers with less than 2,500 units are categorised as supported housing or housing for older people. Given the association between cost and supported housing stock it is therefore unsurprising that the median cost per unit for a registered provider in this group is £4,880. which is 32% above the sector median.

6.19 The average new supply (social) as a percentage of total stock for the largest registered providers is 1.8%, which is 18% higher when compared to the sector median. The fact that the largest providers are disproportionately likely to operate in London, where demand for new housing is greatest may be a contributory factor. These registered providers have also developed significantly more new supply non-social properties compared to the rest of the sector. This is likely to be, in part, due to the greater capacity of the largest providers to diversify into more commercial activity. It may also be due to the concentration of activity in London and the South East where, until the recent market slowdown, the prospects for generating surpluses through market sales were greatest.

6.20 The largest registered providers reinvested 6.3% of their assets’ value into new and existing housing stock, which is 9.6% higher compared to 2018. This is consistent with the concentration of their stock in London, given that providers in the capital have seen large year-on-year increases, particularly in repairs and maintenance.

6.21 Conversely, registered providers with fewer than 2,500 units are less likely to develop at the same rate as their counterparts. As a result, they also have lower levels of overall reinvestment. However, as noted above these registered providers are predominantly characterised by higher levels of care and support compared to most other groups. Over a quarter of registered providers in this group are supported housing or housing for older people organisations, some of whom provide very high levels of specialist care. Reinvestment in existing housing stock per property within this group is £749 which is 5% above the sector average.

6.22 Strikingly, the cohort with the highest level of new supply (social) with a median of 1.9% of existing stock is the registered providers who range between 2,500 to 4,999 units. This cohort of registered providers is quite diverse and apart from their size band, development does not appear to be driven by any other key variables such as geographical location or proportion of supported housing stock. Of the 36 registered providers that are included in this group in 2018 and 2019, over a third of them increased their delivery of new supply units by 50%.

6.23 Our analysis of registered providers’ business plans suggest that this reflects the profiling of registered providers’ capital programmes. Amongst these smaller organisations there is a greater likelihood that development will be ‘lumpy’, as a single scheme can lead to very high percentage variations in supply from one year to the next. The largest providers are more likely to be able to smooth their development profile due to a wider span of activity and the ability to phase long-term programmes.

7. Annex A: Summary of Value for Money metrics and methodology

7.1 This publication, along with the VfM metrics dataset, provides registered providers with a useful comparative baseline for annual reporting and monitoring of trends. The dataset includes the metrics for all registered providers with more than 1,000 properties at both a group and an entity level. For consistency, the metrics for individual registered providers have been calculated on the basis set out in the regulator’s metrics technical note, using the FVA electronic accounts data submitted by registered providers.

7.2 Most of the metrics are set at a group level and take account of registered providers’ core activity, which for most registered providers is the provision of social housing lettings. It also takes account of non-social housing activities in unregistered subsidiaries and joint ventures [^23] which provides a comprehensive assessment of registered providers’ performance. The exception to this is the delivery of new non-social housing through joint ventures, which is excluded for consistency reasons.

7.3 We encourage registered providers to use the regulator’s published metrics to benchmark and challenge performance against relative peer groups, both at a sector and sub sector level. The latest VfM metrics dataset is available on the website with this report.

7.4 The analysis for 2019 is based on 217 registered providers compared to 230 in 2018 and 229 in 2017. The number of registered providers has reduced due to an increased number of mergers and group restructures that have taken place over the last three years. This also means that the number of very large registered providers (greater than 30,000 units), has increased and they now represent just over 45% of the total stock owned and or managed in the sector.

7.5 Quoted quartile ranges apply to performance on individual metrics, so a provider may be in the upper quartile for one metric and the lower quartile for another.

Table 6: Value for Money metrics

| Metric | Subdivision - consolidated, social housing or both | Metric description |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Reinvestment % (in existing homes and new homes) | Consolidated | Scale of investment into existing housing and acquisition or development of new housing in relation to the size of the asset base |

| 2. New supply delivered % | Consolidated and social housing | Units acquired or developed in year as a proportion of existing stock [^25] |

| 3. Gearing % | Consolidated | Proportion of borrowing in relation to size of the asset base |

| 4. EBITDA MRI Interest cover % | Consolidated | Key indicator for liquidity and investment capacity |

| 5. Headline social housing cost per unit | Social housing only | Social housing costs per unit |

| 6. Operating margin % | Consolidated and social housing | Operating surplus (deficit) divided by turnover (demonstrates the profitability of operating assets) |

| 7. ROCE | Consolidated | Surplus/(deficit) plus disposal of fixed assets plus profit /(loss) of joint ventures compared to total assets |

© RSH copyright 2020

This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned.

Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent via enquiries@rsh.gov.uk or call 0300 124 5225 or write to:

Regulator of Social Housing

Level 2

7-8 Wellington Place

Leeds LS1 4AP