A guide to good practice on port and marine facilities

Updated 15 April 2025

Introduction

This guide is intended to supplement the Ports and Marine Facilities Safety Code and it contains useful information with more detailed guidance on several issues relevant to the management of ports and other marine facilities.

The Code and this guide are applicable both to statutory Harbour Authorities and to other marine facilities which may not necessarily have statutory powers and duties.

These are collectively referred to in the Code as ‘organisations’, and may include, but not be limited to, the following examples:

- Competent Harbour Authorities (authorities with statutory pilotage responsible for

- managing a pilotage service)

- Municipal Port or Harbour Authorities

- Trust Port or Harbour Authorities

- Private Port or Harbour Authorities

- Marine berths, terminals or jetties

Whilst it is applicable to all ports, this guide should be applied reasonably and proportionately to each port.

It is designed to provide general guidance and examples of how an organisation could meet its commitments in terms of compliance with the Code.

This Guide should not be viewed as the only means of complying with the Code and for some organisations, it may not be the best means of achieving compliance.

Exposure from failing to comply with best practice

The following extract is from a successful prosecution of a Harbour Authority which was found to fail in its duty to adequately implement four foundational elements of PMSC compliance. This case demonstrates the importance that courts may place on authorities or organisations adopting ‘industry best practice’ and the exposure that they may face if they fail to take adequate steps towards compliance.

The Harbour Authority was subsequently fined for contraventions under section 3(1) of the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974:

To the charge that it was the Port Authority’s duty under the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974, Section 3, to conduct their undertaking in such a way as to ensure, so far as was reasonably practicable, that persons not in their employment who may be affected by the conduct of the Harbour Authority’s undertaking were not exposed thereby to risks to their health or safety.

Part of the indictment read that:

You failed to provide a safe system of work in that you did fail to provide a Safety Management System to reduce to a level as low as reasonably practicable the risks associated with marine operations in the Harbour Area, in terms of the Port Marine Safety Code, and failed to appoint a suitable individual or individuals to share the function of ‘Designated Person’ to provide you as the Duty Holder with independent assurance that your Safety Management System was working effectively and to audit your compliance with the Port Marine Safety Code.

Like the Code, the Guide does not have any legal force, though it does refer to existing legal powers and duties. Furthermore, while it describes typical legal powers and duties, it is not practicable for this Guide to cover the specific legal position for each Harbour Authority or organisation, and it should not be relied on for that purpose.

The Guide has been developed with representatives from industry, the Department for Transport (DfT) and the MCA. The Guide is designed to be a living document; one that will be maintained by the ports industry and can be reviewed and updated on an annual basis.

Proportional compliance

With the wide range of ports and marine facilities specified within its text, the Port and Marine Facilities Safety Code needs to remain flexible enough to be adopted by all. Therefore, when assessing compliance against the Code a proportionate approach helps provide a practical solution for all. Whilst it is expected that all 10 sections of the Code need to be considered by all the extent of compliance that is required under each section will vary. Some sections/part sections might be able to be scoped out completed, e.g. the pilotage sub section would not be relevant to facilities without CHA status.

Scoping exercise

When assessing the relevant level of proportionate compliance, a scoping exercise should be conducted, taking the form of a gap analysis or similar. This should form the basis for assessing compliance with the Code for each organisation and should record how each part of the Code is relevant to the operations, procedures, or processes of the organisation. Where any subsection or significant amounts of a section are scoped out, then a brief explanation of how this was established should be recorded.

Scoping exercise guidance by Code sections

The scoping exercise needs to be conducted by suitably trained and experienced personnel with knowledge of the organisation and its operations.

1. Duty Holder

All organisations should have a Duty Holder, who is responsible for ensuring accurate assessment against the Code. As all organisations have a responsibility as a legal entity, this route of escalation of responsibility and decision making through the organisation should allow for a suitable Duty Holder to be identified.

2. Designated Person

All facilities should have a suitably qualified and experienced Designated Person, able to provide the Duty Holder with independent assurance that the requirements of the Code are being met. The Designated Person section provides guidance on options that allow for differing sizes of facilities, such as reciprocal arrangements.

3. Legislation

The relevant applicable legislation should be identified. Where an organisation is not a Statutory Harbour Authority (SHA) then some ports and harbours legislation may not be applicable, however other legislation such as Health and Safety will still apply and should be identified. Bylaws from an authority the organisation resides within may also need to be identified. Whilst it is reasonable for many facilities not to have their own Harbour Order, the requirement to keep powers and duties under review applies to all facilities. Therefore, the assessment of the suitability of their current powers, along with any need to seek further powers if required, should be recorded.

4. Duties and powers

Many specific duties and powers come out of specific legislation such as a Harbour Act, therefore where legislation does not apply to the facility, it would be reasonable to scope these out of their compliance. However, consideration should also be given to common law duties such as duty of care to users to ensure these are identified and understood.

5. Risk Assessments

Risk Assessments are a key requirement under safety legislation and codes and are therefore a requirement for all facilities. However, whereas an SHA would need to look at Risk Assessments for overall navigation safety within their defined limits, a small facility may only need to risk assess the area and tasks they control.

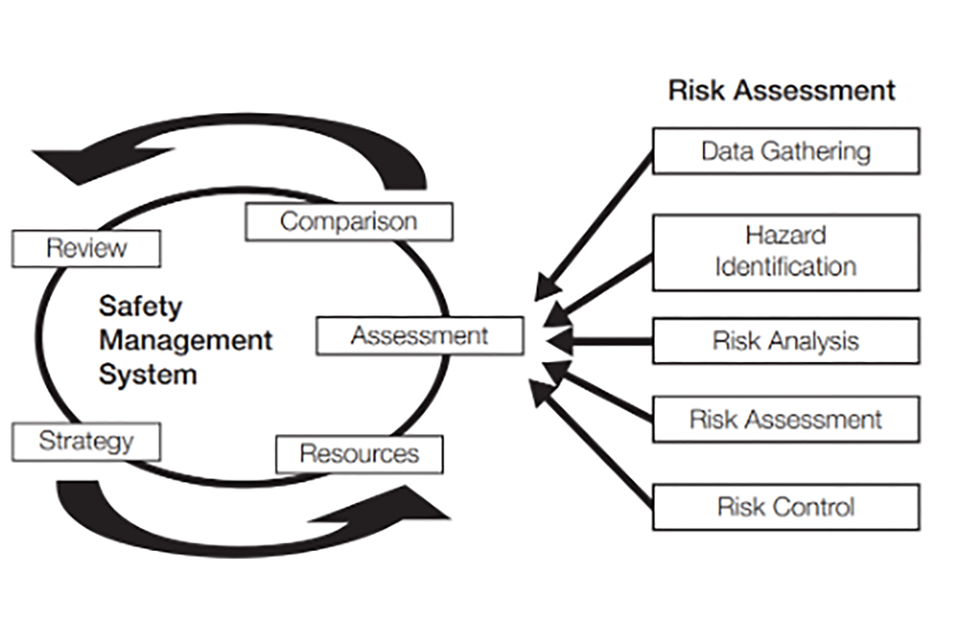

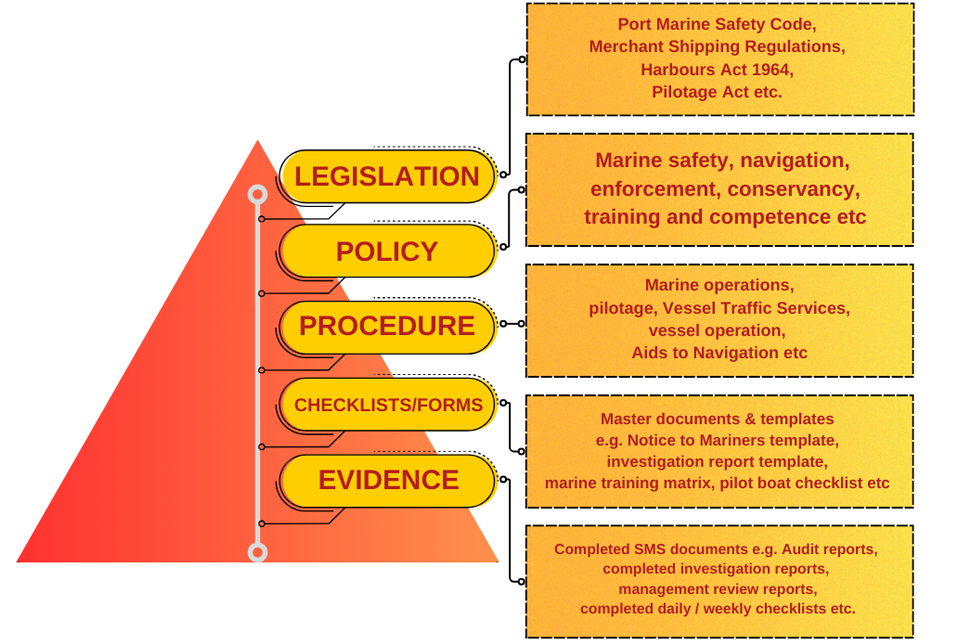

6. Marine Safety Management Systems

A Marine Safety Management System (MSMS), to varying extents would be expected. In its most basic form, it should include any company Health, Safety or Environmental policies as well as any operational instructions and procedures that are in place. The Risk Assessments should then guide additional requirements beyond this. Where additional procedural or competency-based controls/mitigations are identified, then these elements should also be incorporated into the MSMS. Where a facility adjoins, overlaps, or resides within another facility, then they should be aware of any elements of the other facilities MSMS that apply to them, such as permit to work requirements.

7. Review and audit

Internal review and audit of systems should be in evidence, with the policy and frequency covered by a statement within the MSMS. These measures should be appropriate for the complexity and changeability of the MSMS. External audits fall under the responsibility of the Designated Person.

8. Competence

As a minimum there should be evidence of the competence and suitability for the roles of the Duty Holder and Designated Person. Other roles coming under this section will vary and should include those that have duties relating to the safety of marine operations. A Harbour Master (for an SHA) or role covering equivalent responsibilities should be identified.

9. Plan

To help demonstrate their commitment to marine safety, all organisations should publish a safety plan to illustrate how its policies and procedures will be developed and implemented to satisfy the requirement of the Port Marine Safety Code and improve safety every three years. The Duty Holder should also publish an assessment of the organisation’s performance against the plan. The degree of both the content and detail of the plan is very much dependent on both the size of the facility and level of marine activity.

10. Conservancy duty

Regardless of the size of the facility, all authorities have a duty to conserve their facilities to ensure that they are fit for use by all who use them and a duty of care to ensure that all vessels can utilise them safely. To achieve this, users of their facilities should be provided with adequate and up to date information regarding the conditions likely to be experienced. The degree of information and how it is shared will be dependent on the size of the facility and the level and frequency of its use.

Stating compliance

It is still the Duty Holders responsibility to state compliance for their facility once every 3 years during the compliance exercise, which will be announced by the MCA through a Marine Information Notice (MIN). The only exception to this is referenced in section 6.18 of the Code, where an SHA may include named facilities within their limits if there is a significant overlap in the safety management. However, this is only when an agreement is in place between the SHA and the facility.

Section 1: Duty Holder

1.1 Introduction

This section provides guidance on the following:

- demonstrating compliance with the Code

- publishing commitment to the Code

- specific policies on management of navigation, navigational safety, and environmental protection

- ensuring adequate resources are made available

- job descriptions

- operating manuals.

1.2 Summary

Section 1 of the Code states that the Duty Holder is accountable for their organisation’s (e.g., individual port, statutory harbour, terminal, marina, pier or marine facility) compliance with the Code and its performance in ensuring safe marine operations.

It details how that responsibility is discharged and is based on the following general principles:

- The Duty Holder is accountable for safe and efficient marine operations. The Duty Holder should make a clear published commitment to comply with the standards laid down in this Code.

- Executive and operational responsibilities for marine safety must be clearly assigned, and those entrusted with these responsibilities must be appropriately trained, qualified, experienced, and answerable for their performance.

- A ‘Designated Person’ must be appointed to provide independent assurance regarding the effective operation of its MSMS. The Designated Person must have direct access to the Duty Holder.

1.3 Demonstrating compliance with the Code

Compliance with the standards set by the Code is achieved in stages.

- Review and understand existing powers based on local and national legislation.

- Confirm compliance with the duties and powers under existing legislation.

- Assess all risks and consider means of eliminating/reducing them to ALARP (As Low As Reasonably Practicable).

- Operate and maintain a Marine Safety Management System (MSMS) based on Risk Assessment to ensure proper control over marine operations.

- Use appropriate standards of qualification and training for all those involved in safety management and execution of relevant services.

- Establish robust procedures for auditing performance against the policies and procedures to comply with the Code.

- Monitor the standard achieved using appropriate measures and publish the results.

The Code requires all organisations to demonstrate compliance with the Code by developing appropriate policies and procedures relevant to the scope and nature of the marine operations that take place within the organisations authority.

An organisation must:

- Record and publish its marine policies and make available supporting documentation if required.

- Set standards of performance that it aims to meet.

- Regularly review and periodically audit actual performance.

- Publicly report on PMSC performance on an annual basis.

1.4 Publishing commitment to the Code

Implementing the Code is a matter of policy to be adopted by each organisation. This would include a commitment to the publication of a policy statement or periodic reports.

Organisations must develop, and once adopted, publish the policies which allow them to achieve the required standard. These include reports of their formal periodic reviews, setting performance against their plans and against the standard in the Code. As a minimum, plans and reports should be published every three years.

These policies and procedures must include a statement committing the organisation to undertake and regulate all marine operations in a way that safeguards the harbour, its users, the public and the environment.

The Code does not prescribe a form by which organisations are to report publicly regarding the safety of marine operations, but utilising websites for publishing reports and policies is often the most appropriate approach.

It is important that each organisation owns their own management plan, and it is for the Duty Holder to decide the priority, emphasis, and wording of the plan, just as much as the policies and procedures.

Some organisations will prepare statements specifically for the purpose, others may include a separate chapter in their annual report.

A management or business plan is likely to address more than marine operations and it is appropriate that these are set within this context. The coherence of a single document, or suite of linked documents, can be an advantage to ensuring that nothing is missed.

The reports required by the Code should include the following components:

- a statement of the aims, roles, and duties of the organisation as Duty Holder

- the overarching policies and procedures of the organisation to achieve those aims, including the commitment to implement the Code

- the objectives which support the overarching plans and policies

- a means of measuring their achievement against those objectives

- a review of how far the organisation has achieved its aims and objectives, and of changes it proposes to its policies and procedures.

To have any practical effect, published aims and objectives need to be under-pinned by statements of policies and procedures, e.g., a training policy must be applied by adopting appropriate training and competence standards.

Aims and objectives are linked to the identified risks which are assessed and managed through its Safety Management System. The risks relate directly to the nature of the trade and operations within the port or facility.

Any changes in the nature of the business will also affect the risk. It is important for an organisation to consider the cost of managing different risks created in this way.

Some risks will remain even with limited commercial shipping activity, e.g., if the public retain access to the water. These may become significant if the revenue to manage them is reduced. In such circumstances it may be necessary to mitigate risk by regulatory action.

These aims may be linked to other functions, for example those of a company, a local authority, or other statutory body entrusted with harbour functions.

A statement of aims, encompassing marine operations may already have been made in a document relating to those functions e.g., a company annual report, a management plan, or some other policy statement.

Such statements should be the subject of regular review to ensure that they continue to fully reflect the commitments made pursuant to the Code.

The following sample statements illustrate the type of aims that an organisation might adopt to illustrate its commitment to its duties:

- Undertake and regulate marine operations to safeguard the harbour/ organisation, its users, the public and the environment.

- Run a safe, efficient, cost-effective, sustainable harbour/facility operation for the benefit of all users and the wider community.

- Fulfil its legal responsibilities whilst meeting the changing needs of all marine users.

- Maximize the quality and value for money of its services, and to maintain dues at a competitive level to attract users to the harbour or facility.

- Meet the national requirements in the Code.

- They must also recognise, explicitly, that the Duty Holder is accountable for meeting the standard the Code requires.

Following an organisations initial statement of compliance with and implementation of the Code, they should thereafter publish details of their formal periodic reviews, setting performance against their plans and against the standard in the Code.

1.5 Specific policies on management of navigation, navigational safety, and environmental protection

In compliance with the requirements of the Code, the organisation/Harbour Authority will discharge where applicable its general and specific statutory duties in respect of:

- the regulation of traffic and safety of navigation within its authority

- the conservancy of the harbour and its seaward approaches

- the protection of the environment within the harbour and its surroundings

- ensuring as far as reasonably practicable the safety at work of its employees and other persons who may be affected by its activities

- facilitate the safe movement of vessels and craft into, out of, and within the harbour/facility

- conduct the functions of the Authority with special regard to their impact on the environment

- prevent acts of omissions which may cause personal injury to employees or others, or damage to the environment

- create and promote an awareness in employees and others with respect to safety and protection of the environment

- work with government agencies and others to comply with national legislation in respect of the management of environmentally designated areas and the biodiversity of harbour waters. This includes ‘where technically feasible and not disproportionately costly,’ measures to achieve ‘good ecological statuses.

1.6 Ensuring adequate resources are made available

It is recommended that all Duty Holders take time to gain a full insight and understanding of the organisations marine activities, marine Safety Management System and supporting systems. This can be achieved through a combination of briefings and operational visits. It is also important that the Duty Holder receives training / briefing on the PMSC specific to their roles and responsibilities. Organisations should also consider implementing a policy of PMSC Duty Holder refresher training.

Where the Duty Holder is defined as a Harbour Board, consideration should be given to appointing a member to the board who has relevant maritime experience, and who can function as the initial point of contact for the Designated Person. An authority’s principal officers holding delegated responsibilities for safety would normally be expected to attend board meetings.

The Duty Holder is responsible for ensuring that adequate resources are provided to officers to enable them to manage marine operations effectively and to adhere to the stated marine and navigation policies, procedures, and systems, recognising that proper discharge of the organisations duties will otherwise be compromised.

This includes adequate resources for training which needs to be reflected in the relevant policy.

It is important that executive and operational responsibilities be assigned appropriately by organisations to suitably trained personnel. Training needs to be appropriate to the responsibilities assigned to everyone with a responsibility for the safety of marine operations.

In smaller organisations, where these functions are combined, it is important that there is a proper separation of safety and commercial functions.

1.7 Job descriptions

The use of formal job descriptions is considered good practice.

Some jobs related to marine operations are formal statutory appointments, e.g., Harbour Master, while others are related to legal functions and the exercise of the authority’s statutory powers.

The assignment and delegation of legal functions including statutory powers must be formalised.

A Safety Management System also demands that the roles and functions upon which its operation depends are formally documented.

Visible delegation through job descriptions also provides a level of accountability in the measurement of achieving objectives – by showing that somebody has been given responsibility for a specific task.

1.8 Operating manuals

Operating manuals help to establish an auditable link between this Guide and the procedures adopted by each organisation. They seek to provide guidance on how to undertake a specific task.

It will sometimes be the case that objectives also correlate to a section in an operating manual. Long term or standing objectives should be assessed to see if their achievement might usefully be referred to in a manual.

An organisation’s management or business plan might also be supported by documents which form part of the audit trail.

Each harbour or facility has individual characteristics, conditions, position, and mode of operation. Harbour Authorities are equally varied in type and size. Local powers and duties have therefore been conferred by local legislation, created specifically for the Harbour Authority to which it relates, so that each individual harbour may be operated efficiently and safely.

Local harbour legislation provides a legal framework within which the whole undertaking is conducted.

Some general legislation on topics contains matters for which a Harbour Authority holds itself accountable under the Code. It will therefore serve a useful purpose for the authority’s policy statement – and those who audit it – to point to the main pieces of legislation which establish its legal status and functions.

1.9 Municipal

Municipality owned ports should consider various factors in determining how they suitably appoint and train their Duty Holders. These include factors such as the structure of the council, relevant experience of councillors and local authority rules.

It is possible to appoint the Duty Holder as the full council and therefore all elected members, a sub-committee or an individual of the council, e.g. the Chief Executive or director. When considering the various options, local authorities will need to consider how they provide suitable and relevant training for the Duty Holder(s), which can be more challenging when it involves many councillors.

Municipal ports have previously sought legal advice on the liability of Duty Holders as some of the language in the PMSC may not be fully compatible with local authority rules. However, and appreciating that, the law can be subtly different around the UK, in general terms as local authority officers in England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales typically act on behalf of their council, in almost all cases it is the council itself, as a corporate body, who will be responsible for any unlawful actions.

This can mean that in almost all cases, the description of the Duty Holder as being “accountable” both “individually and collectively” is not possible. However, despite these differences, councils with harbour assets have been advised to look to comply with the PMSC as much as is possible to assess, manage and limit risks and provide a suitable governance structure to oversee port and marine safety. Ports should therefore consider taking their own legal advice regarding the terminology when assessing their duties. Local authority Duty Holders may want to consider substituting the term “accountability”, with the word “responsibility”.

As with all port and marine owners and operators, municipal ports are expected to properly resource and train their undertakings. In England these responsibilities are set out in the DfT’s Ports Good Governance Guidance document.

Section 2: Designated Person

2.1 Introduction

Each organisation must appoint an individual as the Designated Person to provide independent assurance directly to the Duty Holder, through assessment and audit, of the effectiveness of the Marine Safety Management System in ensuring compliance with the Code.

2.2 Summary

The Duty Holder is responsible for appointing the Designated Person and ensuring that this is someone sufficiently qualified and experienced to provide the level of assurance that is necessary to comply with the Code.

There are no specific qualifications required for the role of the Designated Person. Therefore, prior to appointing an individual to the role, the Duty Holder should consider the functions applicable to the role and ensure that the individual is suitably experienced to undertake such functions or is able to attend training courses which will provide the necessary skills.

In considering the appointment the possession of at least one of the following criteria are considered advantageous in ensuring a suitable appointment:

- first-hand operational experience of a port/marine environment

- a current Harbour Master / Deputy Harbour Master at another port, perhaps under a reciprocal arrangement

- a member of the harbour board, provided they meet one of the above criteria and are not directly involved in setting up and maintaining the MSMS.

Additionally, best practice supports the view that a Designated Person should have:

- relevant first-hand experience of the port marine environment and how ports/terminals operate

- appropriate knowledge of shipping, shipboard operations, and port operations

- understanding of the design, implementation, monitoring, auditing, and reporting of Safety Management Systems

- understanding of audit techniques for examining, questioning, evaluating, and reporting.

It is acknowledged that there are numerous criteria than can be applied which lead to the appointment of a suitable Designated Person and it is for the Duty Holder to be demonstrably satisfied that they have adopted the best approach for their circumstances and organisation, as it is they who must demonstrate compliance with the Code.

Designated Person appointments may include someone who:

- works for the same port/group but is not directly linked to the operation of the MSMS

- is an external consultant

- is appointed under a reciprocal arrangement with another port/operator or organisation

- sits as part of a ‘select committee’ or ‘board’ where additional relevant knowledge is available to supplement their direct capabilities

- supplements their capabilities with the assistance of external consultants.

It is not acceptable for the Designated Person to also hold the position of Duty Holder.

Once appointed, specific terms of reference for the Designated Person should be issued that are separate and distinct from any other role the post holder may fill and should clearly identify the accountability of the Designated Person direct to the Duty Holder.

In many scenarios, the Harbour Master, any appointed deputies, assistants, or marine managers are directly involved in assessing and controlling the risks to navigation, as well as overseeing the operation of the Marine Safety Management system.

Therefore, for reasons of both impartiality and independence, they are not ideally placed to provide the necessary assurances to the Duty Holder; and, consequently, in all but extenuating circumstances, it is not recommended that the Harbour Master or anyone who reports through them is appointed as the Designated Person.

Notwithstanding the above, where the Harbour Master of a facility is also appointed as the Designated Person, then it is even more important that an external audit of the Marine Safety Management System is undertaken on a regular basis.

The Designated Person will take appropriate measures to determine whether the individual elements of the MSMS meet the specific requirements of the Code.

These measures will include:

- monitoring and auditing the thoroughness of the Risk Assessment process and the validity of the assessment conclusions.

- monitoring and auditing the thoroughness of the incident investigation process and the validity of the investigation conclusions.

- monitoring the application of lessons learnt from individual and industry experience and incident investigation.

- assessing and auditing the validity and effectiveness of indicators used to measure performance against the requirements and standards in the Code.

- assessing the validity and effectiveness of consultation processes used to involve and secure the commitment of all appropriate stakeholders.

- monitoring and auditing the effective and consistent application of the MSMS on port marine / facility operations

The role of the Designated Person does not absolve the Duty Holder and/or board members of their individual and collective responsibility for compliance with the Code.

Section 3: Legislation

3.1 Introduction

This section provides guidance on the following:

- reviewing a Harbour Authority’s powers/legal status, including associated policies and procedures

- directions and byelaws

- harbour revision orders

- licensing

- enforcement.

3.2 Port marine safety legislation

There is a substantial body of applicable general national legislation, such as the Merchant Shipping Act 1995, but many of the principal duties and powers of a Harbour Authority are in local Acts, or orders made under the Harbours Act 1964.

This legislation includes powers to make byelaws. Section 3 of the Code explains how the local legislation can be changed.

A list of some examples of legislation applicable to ports in the UK include:

- Harbours, Docks and Piers Clauses Act 1847 - Construction of harbours, right to buy/lease land, Collection of fees, powers of a Harbour Master, Discharge of cargos/ballast, making byelaws, regulating the admission of vessels into or near the harbour, dock, or pier, regulating the shipping and unshipping, of all goods, preventing damage or injury to vessels etc.

- Dockyard Ports Regulation Act 1865 – Appointment and authority of the Kings Harbour Master.

- Harbours Act 1964 – Helped to modernise the system for Harbour Authorities levying charges on those using the harbour. Provides Harbour Authorities with a general power to set ship, passenger and goods dues.

- Dangerous Vessels Act 1985 - Empowers Harbour Masters to give directions to prohibit vessels from entering the areas of jurisdiction of their respective Harbour Authorities or to require the removal of vessels from those areas where those vessels present a grave and imminent danger to the safety of any person or property, or risk of obstruction to navigation.

- The Dangerous Substances in Harbour Areas Regulations 1987 - Regulations apply in every harbour area in Great Britain.

- Pilotage Act 1987 - Requires competent Harbour Authorities (CHA) to keep under consideration what pilotage services are needed to secure the safety of ships and gives them powers to: make pilotage compulsory and levy charges for the use of a pilot; grant Pilotage Exemption Certificates (PEC); and, authorise pilots within their district.

- Merchant Shipping Act 1995 - Consolidates much of UK’s maritime legislation.

- Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009 - Establishes and empowers the Marine Management Organisation. Establishes rights of access to land near the English and Welsh Coast, makes provision in relation to works which are detrimental to navigation.

3.3 Legislation review

The first step for the organisation is to take stock of the powers, policies, systems and procedures that are in place having regard to an overall assessment of the risks to be managed. The level of detail required will depend partly upon the extent to which appropriate systems are already in place, but also influenced by the replies to your consultation, and publication of the safety policies adopted by each authority. It is a requirement of the Code that each authority’s policies and procedures should demonstrate that they are based upon a full assessment of the hazards which must be managed to ensure the safety of the harbour and its users.

All legislation, including byelaws and directions, should be reviewed on a regular basis, preferably annually, to ensure that they remain fit for purpose in changing circumstances. The Code explains that the requirements for marine safety will be determined by a Risk Assessment. If the legal responsibilities cannot be discharged effectively using available powers and by other measures, and that authority does not have the powers to rectify the situation, then it should seek the necessary additional powers. In addition, it is good practice and effective governance to dispense with redundant or obsolete legal functions.

It is essential that all Harbour Authorities are aware of the legislation that affects them which includes local legislation. Harbour Authority boards and managers must understand clearly the meaning of all the relevant legislation which affects their harbour to avoid failing to discharge their duties or exceeding their powers.

3.4 Directions (usually referred to as special directions)

Where sections 52 and 53 of the Harbours Piers and Clauses Act 1847 have been incorporated into a Harbour Authority’s local legislation, a Harbour Master has powers of direction to regulate the time and manner of ships’ entry to, departure from and movement within the harbour waters, and related purposes. These powers are assigned for the purpose of giving detailed directions to specific vessels for specific movements, unless the powers have been extended for other purposes. Harbour Master’s directions may be referred to as ‘special directions’ to distinguish them from ‘general directions’ given by the authority itself. Special directions are not for setting general rules but relate to specific vessels – or in an emergency, to a class of vessels on particular occasions.

The powers of direction are also exercisable by a Harbour Master’s assistant – or any other person designated for the purpose in accordance with the authority’s statutory powers. It is an offence not to comply with directions, although the master – or pilot – of a vessel is not obliged to obey the directions if they believe that compliance would endanger the vessel. It is the duty of a Harbour Master in exercising these powers to consider the interests of all shipping in the harbour. Directions may include the use of tugs and other forms of assistance.

It is best practice to provide staff who have delegated powers of a Harbour Master to issue special directions, with training and specific guidance and templates that help to ensure clarity on how and when a special direction can be delivered.

3.5 General Directions and Harbour Directions

Some Harbour Authorities have powers, through their local authority legislation, to give ‘general directions’, enabling them, after due consultation, to lay down general rules for navigation (subject to certain constraints) and regulate the berthing and movements of ships. These carry the force of law but are often easier to achieve and amend than using byelaws, and thus act as a useful mechanism for managing navigation and furthering safety. General directions and procedural provisions involve publication of proposed directions, but they do not need to be confirmed by the Secretary of State as is the case with byelaws.

Harbour Authorities would be well advised to secure these powers to support the effective management of vessels in their harbour. This can be achieved in two main ways:

- Through Harbour Revision Order under section 14 of the Harbours Act 1964 (the 1964 Act).

- Through designation under section 40a of the 1964 Act with the power to give harbour directions for the movement, mooring, management and equipment of ships. These powers are of the nature of general directions to support the effective management of vessels in their harbour waters. A non-statutory Code of Conduct on the use of the section 40a power has been agreed by the Department in conjunction with organisations representative of ports and port users. Further guidance on harbour directions can be found by using Regulatory Triage Assessment (legislation.gov.uk).

3.6 Harbour Revision Orders

The Harbours Act 1964 enables a Harbour Authority to amend statutory powers in their local legislation. It can be used to achieve various outcomes, one of which is to impose or confer additional duties or powers on a Harbour Authority (including powers to make byelaws). It can also be used in the context of the Code to substitute or amend existing duties and powers. It could be used for the purpose of (but not limited to):

- Improving, maintaining or managing the harbour marking or lighting the harbour, raising wrecks therein or otherwise making safe the navigation thereof.

- Regulating the activities of other individuals and groups in connection with the harbour and the marine/shore-side interface.

- Extending controls into the approaches of a harbour (for example, to extend compulsory pilotage beyond the harbour).

All proposals should, as far as is practical, be subject to extensive local consultation.

The processing and determination of harbour revision orders and other specified functions under the 1964 Act has been delegated to the Marine Management Organisation (MMO) for English harbours and Welsh non-fishery harbours, and other devolved authorities:

- Northern Ireland, Dept for Infrastructure

- SNI Scotland, Transport Scotland

- Wales, Natural Resources Wales.

The Marine Management Organisation (MMO) has issued guidance on applying for a harbour order. Organisations should discuss requirements and procedures with the appropriate authority and consult relevant authorities and interested parties locally before making an application. Organisations can request an informal review of the draft order before making an application to identify any fundamental issues. It is also recommended that independent legal advice is sought.

The authority assigned the responsibility will need to be satisfied that the order would:

- secure the improvement, maintenance or management of the harbour in an efficient and economical manner

- facilitate the efficient and economic transport of goods by sea

- be in the interests of sea-going, commercial and leisure vessels.

There are similar provisions for varying or abolishing such powers. If a harbour has become no longer viable or necessary, commercially speaking, partial or complete closure of that harbour can be achieved through a harbour closure order under section 17A of the 1964 Act and such orders will be handled by the appropriate government department dealing with Transport. For harbours which are still commercially viable, partial closure of that harbour can be achieved through a harbour revision order.

3.7 Byelaws

Many Harbour Authorities have powers under their own local legislation, for example if they have incorporated section 83 of the Harbours, Docks and Piers Clauses Act 1847, which allow them to make byelaws.

Byelaws may cover a wide range of subjects within the harbour and on the port estate, for example, the quayside and the regulation of vessels within the port.

On the marine side, this might include:

- navigational rules

- general duties of Masters

- movement of hazardous and polluting goods

- alcohol and drugs

- ferries, lighters, barges and tugs

- noise and smoke

- recreational craft including water-skiing, personal watercraft

- bathing

- speed limits

- licensing port craft

- licensing personnel (e.g. boatmen).

There is a brief description of the function and making of harbour byelaws under paragraphs 4.11 – 4.13 of the Code. The procedure for each authority is in its local legislation either through incorporated provisions, or its own provisions. Many Harbour Authorities now incorporate the more modern procedural provisions set out in sections 235 – 238 of the Local Government Act 1972. The 1972 provisions have been adapted by some authorities, to allow byelaws to be modified upon confirmation by the Secretary of State, as Section 237 (7) of the 1972 Act by itself does not permit this.

Making and changing byelaws is often perceived as a difficult and prolonged process. However, the process can be expedited if Harbour Authorities avoid common pitfalls and take the following steps:

- assess the risk and decide whether a byelaw would be the most appropriate method of mitigating the risk.

- make sure your authority has the relevant powers to make byelaws for the measures that are being proposed.

- make sure you can justify your proposal to consultees. Demonstrate that you have considered other options in addition to legislation. All proposals to improve safety of navigation in the harbour should be supported by a formal Risk Assessment.

- make sure you consult on your proposal before drafting the byelaw and again before you present the byelaw to the relevant Minister.

- demonstrate to the relevant minister or appropriate authority that the proposals can be clearly enforced and that resources exist for this purpose.

- get experienced advice or use a legal professional to draft the byelaw on your behalf.

- be persistent – Initial opposition to a proposal does not mean that it will fail. Try to resolve any confusion by addressing problems at the earliest opportunity and if appropriate, revise the proposal. If differences are unable to be resolved, you should still present the draft byelaw to the relevant minister for consideration. In these circumstances the applicant authority should give a full and reasoned explanation of the differences supported by a safety case and risk analysis.

Possible consultees might (but not necessarily) include:

- leisure users – sailors

- motor cruiser-users

- rowers

- personal watercraft users

- swimmers

- line handlers

- tug operators

- various associations and users’ organisations

- trade unions

- vessel owners

- pilots

- vessel operators – inland waterways and deep sea

- local communities

- other local regulators – e.g., MCA

- adjacent port authorities

- local authorities

- RNLI

- RYA

- the Amateur Rowing Association (ARA).

3.8 Licensing

Some Harbour Authorities have responsibility for licensing port craft, personnel (local watermen) and works in, or adjacent to, navigable water. Some examples of activities which the authority may need to license, or seek powers to licence include the following:

- line handlers

- commercially operated craft e.g. local domestic ferry or passenger vessels

All Competent Harbour Authorities have power in the Pilotage Act to approve or issue a license for pilot boats. In all these processes, proper and appropriate standards and competencies need to be established and applied uniformly in the interests of safety and consistency. In practice, the best way to achieve this is by following and certifying pilot boats and crews under the appropriate vessel code of practice, such as the Workboat Code (GOV.UK) - The safety of small Workboats and pilot Boats – a Code of Practice (as amended). See below section 4.5 on pilot launches.

3.9 Enforcement

Byelaws and directions adopted to manage identified marine risks must be reinforced by an appropriate policy on enforcement; and each authority should have a clear policy on prosecution of those who breach byelaws and directions, which is in line with the safety assessment on which they are based. The enforcement policy should consider a wide range of possible measures of appropriate and proportionate enforcement, examples include:

- guidance and training with stakeholders

- verbal warnings and guidance, e.g. from afloat patrol staff or the HM

- written warnings

- formal prosecution through the courts

Authorities should also consider publishing an enforcement policy statement which can be displayed and promulgated to users. The statement should summarise and highlight that the authority has various duties and powers and explain the various approaches the authority may take regarding enforcement, from education through to court action if deemed necessary.

3.10 Consultation

Consultation is crucial to ensure that relevant parties are consulted on areas relevant to them, and this is summarized by:

- objectives of consultation in the context of the Code

- statutory requirement to consult

- benefits of consulting informally.

Safety in the port marine environment is rarely just a matter for the individual organisation e.g., Individual port, statutory harbour, terminal, marina, pier, marine facility or its third-party contractors. Users of any facility are required to minimize risk to themselves and others. In doing so they must be able to put forward to the organisation any views on the development of appropriate safety policies and procedures.

It follows therefore that organisations need to consult, as appropriate with two main groups: marine users, both commercial and leisure, in addition to any associated local communities.

While port marine operations may be understood by experienced port practitioners, they are less so by the wider public and some recreational users. It is therefore important to maintain an appropriate level of involvement with these groups.

Some substantial objectives of ‘consultation’ should be:

- Conveying to employees, users or others what some of their responsibilities are regarding their work or activity in the harbour or facility.

- Understanding and acceptance of the Duty Holder’s role and responsibility under the code as well as the Duty Holder’s policies and procedures.

A Safety Management System is only effective if the organisation responsible takes active measures to involve and secure the commitment of those involved. This applies both to the Risk Assessment, and to the subsequent operation, maintenance and ongoing development of the Safety Management System. Not all will be the organisations employees.

Consultation takes various forms. There are some specific statutory obligations. These should form the basis for general consultation with users and other interests. There should also be established formal procedures for consulting employees – including, in the case of Marine Operations, any person not directly employed, but who offers their services under a contract for services, either directly to the port, or indirectly through the ship-owner or their local representative.

3.11 Statutory and non-statutory consultation

The procedures for harbour orders revising the statutory powers and duties of an authority include explicit guidance on consultation and rights to objection. The appropriate Minister will direct who is to be statutorily consulted by service of notice.

There are also well-established procedures for advertising the making of byelaws which will be found in each authority’s local legislation. Modern practice is to base these on the procedures for local authority byelaws. Details of procedures for making harbour orders and byelaws are discussed in Section 1 of the Guide; more information on the former can be found on Good governance guidance for ports - GOV.UK.

In both cases, however, it is good practice, and in the authority’s interests, to have consulted those likely to be affected through ‘informal’ consultation before formalising proposals by applying for a harbour order or making byelaws. It is generally the case that the appropriate Minister does not have power to modify byelaws at confirmation stage – even to consider grounds of objection which the authority has accepted. If an authority is proposing changes to its powers or regulations as a result of a Risk Assessment, and has properly consulted about this, there is more likely to be general acceptance of its formal proposals. At any rate, likely grounds of objection will have been discovered and an opportunity found to deal with these informally.

Harbour Authorities typically consult the appropriate Minister’s officials on draft orders and byelaws. Officials must be careful not to prejudice formal decisions to be taken later and will not therefore be ready as a rule to comment on the merits of proposals. The opportunity will be taken to promote wider consultation: officials giving advice will seek to understand how proposals relate to the Risk Assessment process.

3.12 Consultation during the Risk Assessment process

The general aim of consultation is to provide an opportunity for contributions to be made both to the identification of risk and its management. Risk management often depends less on formal regulation than on winning the understanding of those whose activities create the risk and securing their agreement to safer behaviour. Organisations are therefore encouraged to advertise when they are undertaking a Risk Assessment and seek ways of securing the widest possible response from those likely to both be affected in addition to those able to make a meaningful contribution to the process.

The Code does not require the outcome of Risk Assessments to be published in full, though some organisations may wish to do so. There may be well-found concern that drawing attention to risks would unduly alarm some stakeholders, in which case, the organisation might choose to issue a report outlining its risk management plan to explain the need for various measures that impinge on users. Whichever approach is adopted it is important that users are adequately informed of any measures adopted to mitigate against risks that may affect their activities.

3.13 User committees

Some authorities have established advisory or consultative committees for the purpose of facilitating users’ contributions to Risk Assessment and of informing and updating users on the day-to-day management of marine operations in the port or facility. In some cases, the authority’s local legislation requires them to do so in various ways. It is not necessary, however, for these arrangements to be in the authority’s local legislation. The general approach is to identify the bodies or individuals needed to make such a forum properly representative. There are, however, examples where the authority may ask for a different nominee – a right to be exercised exceptionally and for substantive reasons which could be justified publicly.

The ultimate authority for managing the harbour rests with the legally constituted Harbour Authority. The Harbour Authority does not share its legal functions with a users’ committee or forum; nor is a committee accountable in the way required of Harbour Authorities under the Code. It is good practice to have set out in advance in general terms the circumstances in which it will or will not involve such a committee – for example, where emergency action is required or there are commercial and other confidences.

3.14 Providing information to users

The counterpart of effective consultation arrangements is an effective means of communicating appropriate information, advice and education to harbour/facility users. Organisations should consider the most appropriate and effective methodologies to employ, certainly making use of appropriate technology including social media and websites to reach their target audience.

3.15 Local Lighthouse Authorities

It is important that all Local Lighthouse Authorities who are involved with the establishment, maintenance and navigational marking of the approaches to the harbour, identify all users and provide for effective consultation, notification and advice to ensure that users are fully informed of proposed developments or changes to the harbour as required by the General Lighthouse Authority (GLA). See Section 10- Conservancy Duty for further guidance on conservancy and aids to navigation.

3.16 Consultation with employees, contractors or other related service providers

Whilst responsibility for port marine safety remains with the Duty Holder, employees and others may in turn be accountable to the organisation through contracts of various kinds. While all are responsible for their own safety at work, this does not divide or dilute the organisations particular responsibility.

While decisions on policy and procedure are for the organisation itself to take, they also need to ensure that these decisions are effectively communicated to, and observed by, those whose activities are regulated or affected by these decisions.

A Harbour Authority or organisation is unlikely to employ all those who work in its port or facility. For example, pilots may be engaged through a contract for services with a pilot co-operative; tug crews and others may work for service providers either contracted to the port or to particular terminal operators. All employers have a responsibility for the safety of their workforce. Consulting and involving employees, as appropriate, on the organisations Risk Assessment helps them to discharge that responsibility.

Organisations regulation of port marine activities within their jurisdiction aims among other things to secure the safety of all those engaged in those activities in any capacity. It is to be expected that anybody whose safety is being so regulated may have something to contribute to a Risk Assessment or review of procedures and it is good practice to make an opportunity for them to participate. It may be appropriate in some cases to consult members of these groups through their own employers – and a consensus is most likely to be achieved in this way. At the same time, such groups may also have trade union representatives, who feel strongly that they should have an opportunity to contribute to the Risk Assessment. The Department considers that it is good practice to give provide that opportunity.

Section 4: Duties and powers

4.1 Introduction

This section is primarily directed towards Harbour Authorities, other organisations may however want to consider what legal powers and duties they have or should seek to promote navigation safety.

The duties of a Harbour Authority are of three types: statutory duties, imposed either in the local legislation for that authority or in general legislation, general common-law and fiduciary duties, such as duty of care, loyalty and confidentiality.

The Code identifies several duties and powers regarding the management of the following:

- safe and efficient marine operations

- open port duty

- appointment of a Harbour Master

- byelaws

- directions (usually referred to as special directions)

- general and harbour directions

- dangerous vessel directions

- pilotage and pilotage directions

- towage

- regulation of marine craft

- environmental duty

- emergency preparedness and response

- civil contingency duty

- authorisation of pilotage

- Pilotage Exemption Certificates

- collecting and setting of dues

- aids to navigation

- wrecks

The above areas are based on the following principles:

- Harbour Master should familiarise themselves with the extent of their legal powers under general and local legislation.

- powers to direct vessels are available – and should be used – to ensure safety of navigation.

- dangerous vessels and substances, and pollution, must be effectively managed.

- a pilotage service must be provided if required in the interests of safety.

- properly maintained aids to navigation must be provided, and any danger to navigation from wrecks or obstructions effectively managed.

These principles are developed in separate chapters of the Code, and in this guide.

4.2 General duties and powers

The Code identifies these general duties of Harbour Authorities relevant to port marine safety as the following:

- safe and efficient port marine operations

- Open Port Duty

- conservancy duty, including responsibility for the safe operation and maintenance of marine facilities

- revising duties and powers

- environmental duty

- Civil Contingencies duty

- Harbour Authority powers, which include:

- take reasonable care, so long as the harbour/facility is open for public use, that all who may choose to navigate in it may do so without danger to themselves, other users’ lives or property.

- conserve and promote the safe use of the harbour/facility and prevent loss of life or injury through the organisation’s negligence.

- have regard to efficiency, economy and the safety of operation in respect to the services and facilities provided.

- take such action that is necessary or desirable for the maintenance, operation, improvement or maintenance / legal requirements of the harbour / facility.

The Code gives an outline of the main related duties.

4.3 Legal duties and powers

Every Harbour Authority’s safety plan must include a statement of the legal duties and powers. Plans and subsequent reports should state when these were most recently reviewed.

Duties and powers – whether in harbour orders, byelaws, general or Harbour Master’s directions – should be developed from a considered approach to risk. Where statutory force is given to an authority’s rules, the authority’s plans should demonstrate that those rules clearly relate to the management of risks. Harbour Authorities should also be able to demonstrate, therefore, that they are equally clearly enforced, and plans should show that adequate resource is available for this purpose. Additional powers should only be sought – and, in the case of harbour orders, byelaws, and harbour directions, will only be granted – on that understanding.

Section 10 of this guide deals with the regulation of navigation; byelaws and directions are tools for this purpose. That section contains more guidance about how they can be used.

4.4 General, Harbour and Pilotage Directions

Port facility users have a specific right to be consulted where they are made subject to general, harbour and pilotage directions. They have no other convenient recourse against unreasonable directions, such as the right of objection to byelaws allows, although the non-statutory Code of Conduct on the use of harbour directions includes a procedure for dispute resolution.

There are sometimes quite specific requirements for the Chamber of Shipping to be consulted. This is to be regarded as a minimum, recognising that the port is likely to have users not represented in this way. Each authority should identify bodies which represent local users and adopt a policy to consult them about directions. They should also consider drawing proposed directions to the attention of other users by alternative means. The Code of Conduct on harbour directions specifically describes the formation of a Port User Group.

4.5 Pilotage

This section provides guidance on the following:

- the Competent Harbour Authority

- the bridge team and pilot

- safety Assessment

- agents and joint arrangements

- pilotage directions

- authorisation of pilots

- training

- pilot exemption certificates

4.5.1 Summary

Chapter 4 ‘Duties and Powers’ of the Code refers to the main powers and duties which Harbour Authorities who provide a pilotage service (as a Competent Harbour Authority (CHA) need to consider under the provisions of the Pilotage Act 1987. The following principles apply:

- Harbour Authorities are accountable for the duty to provide a pilotage service; and for keeping the need for pilotage and the service provided under constant and formal review.

- Harbour Authorities should therefore exercise control over the provision of the service, including the use of pilotage directions, and the recruitment, authorisation, examination, employment status, and training of pilots.

- Pilotage should be fully integrated with other port safety services under Harbour Authority control.

- Authorised pilots are accountable to their authorising authority for the use they make of their authorisations: Harbour Authorities should have contracts with authorised pilots, regulating the conditions under which they work – including procedures for resolving disputes.

4.5.2 The Competent Harbour Authority

CHAs should, through their boards, play a formal role in the recruitment, training, authorisation and discipline of pilots. They should also approve the granting of pilot exemption certificates (PEC) and the discipline of PEC holders.

IMO Assembly Resolution A960 makes several recommendations on how pilotage authorities should approach the training and certification of pilots in respect of certain operational procedures. CHAs are encouraged to act in accordance with this Resolution in the implementation of their duties and powers under the Pilotage Act 1987.

The national occupational standard (NOS) for pilots may be a useful resource in helping authorities to consider the training requirements of authorised pilots and how pilot training manuals might be best produced. Many ports also publish their pilot training manuals which may provide useful templates when considering the production of pilot training manuals. The NOS for pilots is a useful reference and should be referred to when considering pilot training.

It is likely that the Harbour Authority will delegate responsibility for the management of pilotage to the Harbour Master or another qualified executive officer, or in combination. These arrangements need to provide that the delegated powers are defined with clarity for each person; and the statutory role of the authority observed.

4.5.3 Bridge team and pilot

A pilot’s primary duty is to use their skill and knowledge to protect ships from collision or grounding by safely conducting their navigation and manoeuvring whilst in pilotage waters. Nonetheless, the master and bridge team are always responsible for the safe navigation of the ship. Bridge procedures and bridge resource management principles still apply when a pilot is onboard. The bridge team must conduct a pre-passage briefing with the pilot to ensure a common understanding of the Passage Plan prior to its execution. pilots, masters and watchkeepers must all participate fully, and in a mutually supportive manner.

The master and bridge team have a duty to support the pilot and monitor their actions. This includes querying any actions or omissions by the pilot or any members of the bridge team, if inconsistent with the passage plan, or if the safety of the ship is in any doubt.

4.5.4 Conduct

Under provisions of the Pilotage Act 1987 the pilot is not merely an advisor but has legal conduct of the navigation of a vessel:

- 1987 Pilotage Act Sect 31 – “pilot” has the same meaning as in the Merchant Shipping Act 1894 and “pilotage” shall be construed accordingly. Section 742 of the Merchant Shipping Act 1894 states that a pilot will be classed as “any person not belonging to a ship who has the conduct thereof”.

There are numerous cases which illustrate the point, which despite their age are still binding in law:

- The Mickleham (1918). This case considered the meaning of the word “conduct” and concluded that if a ship is to be conducted by a pilot it “does not mean that she is to be navigated under his advice: it means that she must be conducted by him”.

- The Tactician (1971). In this case the judge also considered the meaning of the word “conduct”. And stated: “it is a cardinal principle that the pilot is in sole charge of the ship, and that all directions as to speed, course, stopping, and reversing, and everything of that land, are for the pilot”.

4.5.5 Training

To work effectively with the bridge team, the pilot should be trained in the principles of both Bridge Team Management (the focus being internal and external relationships and operational tasks of the Bridge Team) and Marine Resource Management (the focus being cultural issues and the role of the pilot).

4.5.6 Technical aids

Consideration should also be given to the risk reduction benefits of utilising proven technology that can provide additional complementary support, independent of ship systems, to both pilots and bridge teams.

4.5.7 Assessment

Pilots should be monitored and assessed in the effectiveness of work with the bridge team. This could be through peer review or other form of audit.

4.5.8 Level of mutual support for bridge team

Inevitably the level of mutual support will vary dependent upon several factors including trade, vessel size, systems available and crew numbers. However, the following are minimum requirements:

- capable - competent and properly qualified

- well prepared - e.g. charts, passage plan, machinery state, anchors, crew deployment

- responsive - be alert to the pilot requirements and monitoring the pilot and others’ actions

- co-operative - positively answering pilot’s questions and acting on directions

- acceptable level of English – clear understanding of standard marine vocabulary

- fully familiar with bridge equipment.

4.5.9 Reporting Substandard Performance

Pilots have a statutory duty to report ship deficiencies that may adversely affect its safe navigation to the CHA who should inform the MCA. This mechanism could be used to report substandard performance but if not, then the Safety Management System must include procedures to facilitate reporting to the CHA that can be acted upon immediately if necessary (e.g., if the vessel remains in port). Organisations should report ship deficiencies to their local MCA marine office, a map with contact details is available at Locations of MCA marine offices - GOV.UK.

4.5.10 Providing a service

The 1987 Act requires that the pilotage service provided by any CHA should be based upon a continuing process of Risk Assessment. Operating a pilotage service will involve consideration of the following factors:

- safety assessment

- agents and joint arrangements

- pilotage directions

- boarding and landing arrangements

- consultation

- pilotage regulations

- authorisation of pilots

- contracts with authorised pilots

- training

- rostering pilots

- incident and disciplinary procedures.

The following section gives further guidance on the above main factors that should be considered by any CHA providing pilotage services.

4.5.11 Safety assessment

Section 2(1) and 2(2) of the 1987 Act requires:

- Whether any, and if so, what pilotage services need to be provided to secure safety of ships navigating in or in the approaches to its harbour.

- Whether, in the interests of safety, pilotage should be compulsory for ships navigating in any part of that harbour or its approaches. If so, for which ships under which circumstances and what pilotage services need to be provided for those ships.

The hazards involved in the carriage of dangerous goods, pollutants or harmful substances by ship must be considered. These considerations should be addressed as part of an authority’s overall Risk Assessment and Safety Management System (see Section 5 and Section 6 of this guide).

For the purposes of the Marine Safety Management System (MSMS), the provision of pilotage, whether by authorised pilots or Pilot Exemption Certificate (PEC) holders, is to be treated as a risk reduction measure, and be considered with other possible risk reduction measures to mitigate the risks identified within the Safety Management System and appropriate Risk Assessments.

The decision under Section 2 of the Act to provide pilotage services should be taken in the context of all risk reduction measures. It may be identified therefore that pilotage services would not positively affect risk reduction compared to other risk reduction measures and pilotage services deemed not required. The CHA should, however, be satisfied with the effectiveness of any risk reduction measure before relying on it.

A CHA with the powers to provide an effective and efficient pilotage service must be satisfied that it can do so competently. This means firstly that the CHA has the competence to assess and oversee authorised pilots, and those who may apply for Pilotage Exemption Certificates; and secondly, that they will have sufficient pilotage work to maintain their skills adequately.

It is important to note that an authority has two separate decisions to make:

- to identify the pilotage service required in the interests of safety (Section 2 of the Act)

- the scope of pilotage directions.

The service provided shall cover the requirements of all vessels required to have a pilot by the directions. However, the authority must also consider other points:

- Some vessels subject to directions may hold a Pilotage Exemption Certificate and therefore reduce the overall pilotage requirements.

- A vessel not subject to directions may nevertheless request (or be directed to engage) a pilot in the interests of safety (for example in unusual conditions such as poor weather, reduced visibility, unfamiliarity with, or lack of knowledge of, the port or due to fatigue) which could Increase pilotage service requirements.

- A vessel which holds a Pilot Exemption Certificate may also request the services of a pilot due to unusual environmental conditions, vessel condition or fatigue which will also Increase pilotage service requirements.

The principal point to be remembered is that the authority has a duty to provide the service required in the interests of safety (not in terms of the service required by the pilotage directions). The requirement is determined through the Safety Management System, which may identify alternative risk reduction measures where pilotage, and pilotage directions, would otherwise be needed.

If a risk is identified for which there is no satisfactory alternative to pilotage, the service provided must fully meet the requirements of the Code. Section 2 of the 1987 Act does not allow financial considerations to be used as a justification for not providing a pilotage service.

An authority which identifies the need to provide a pilotage service, incurs an obligation to find and maintain the resources and expertise.

4.5.12 Agents and joint arrangements

An authority may arrange for certain pilotage functions to be exercised on its behalf by such other persons as its sees fit, including a company established for the purpose, or another Harbour Authority. The Secretary of State also has power to appoint one authority as CHA for another’s area. Two or more authorities may arrange to discharge such functions jointly. Under Section 11(2) of the Pilotage Act a CHA may assign all its pilotage functions other than the duty under 2(1) to another CHA. The following arrangements may not be assigned or shared:

- duty to continually review the requirements for a pilotage service

- authorisation of pilots

- arrangement under which its authorised pilots are engaged

- approval of pilot launches

- issuing of pilotage directions

- issuing of Pilotage Exemption Certificates.

These are all key elements which the MSMS should address as required under the Pilotage Act. Where other functions have been delegated, or there is a joint arrangement, the body or authority should be fully consulted in developing the system or consider having a joint Safety Management System. Authorities should also consider seeking a joint system for jetties and berths outside their jurisdiction, where their pilots may be providing a service.

Any delegation or joint arrangement should be subject to a formal contract with any other body used in this way (including another Harbour Authority) which fully recognises statutory obligations which cannot be delegated or shared. The contract should set out the decisions which the delegated or joint body may make, and any conditions to which this is to be made subject. There should be provision in such a contract to terminate the arrangement at any time to enable an authority to carry out delegated or joint functions itself, or to make some other permissible arrangement instead.

4.5.13 Pilotage directions

If a CHA decides in the interests of safety that pilotage should be compulsory in the harbour or any part thereof, it must issue pilotage directions. This requirement Is separate from any decision to provide a pilotage service. As noted above, an authority may decide to provide a service without making pilotage compulsory in some or all circumstances. Vessels are subjected to pilotage directions where the authority has decided that the management of safety so requires.

The authority’s pilotage directions shall define the geographic area within which pilotage is identified as compulsory. These limits should be determined and assessed by means of formal Risk Assessment. If risk is identified in an area outside the statutory limits of a port, then there is a provision for port limits to be formally extended by harbour revision order, so that the risk may be managed. There is special provision in the 1987 Act for such extensions for pilotage purposes only.

Pilotage directions describe how pilotage applies to vessels using the port. The content of the directions should be driven principally by the results of the Risk Assessment. Directions must specify the ships or type of ship, and the geographical area, to which they apply; and in any circumstances in which an assistant pilot must accompany an authorised pilot.

Directions should specify vessel types. Ships have been specified in directions according to size (traditionally by length, but sometimes by draught, tonnage, beam etc.). Risk assessments provide an opportunity to consider the relevance of such criteria – and others, and whether they are the right way of deciding which vessels present a risk that is appropriately managed by compulsory pilotage.

4.5.14 Pilot boarding and landing arrangements

A revised code of practice entitled The Embarkation and Disembarkation of pilots, was prepared jointly by the UKMPA and the BPA, and the UKMPG Marine/Pilotage Working Group, and provides advice on pilot boarding and landing arrangements. CHAs are strongly recommended to refer to this code of practice when considering pilot boat and boarding operational procedures, Risk Assessments and safe systems of work.

Pilotage directions may include such supplementary provisions as the authority considers appropriate. This provision is used to designate pilot boarding and landing positions. The following are examples of considerations applying to the fixing of these positions, especially the seaward position:

- it must be in a safe place to transfer a pilot to and from a vessel

- it must allow for a pilot to be on board where the pilotage directions so require

- it must be where there is sufficient time and sea room to allow a proper master - pilot information exchange.

The requirements might also vary according to different types of vessels – and for other temporary reasons, such as adverse weather. Subject to the following two paragraphs, the boarding and landing position is normally established at the limit to which the relevant pilotage direction applies.

4.5.15 Confirmation of pilot boarding arrangements compliance

Whilst relatively infrequent, several incidents of pilot ladder side ropes parting whilst pilots have been embarking / disembarking have occurred over recent years, some resulting In Injury.

CHAs are encouraged to adopt a control measure which requires the master of any ship boarding or landing an authorised pilot to make a verbal declaration via the local VTS/LPS or pilot cutter directly (if pilots will be boarded before first contact with VTS/LPS), that the pilot boarding arrangements are:

“Properly constructed, recently inspected, in good condition and rigged as per SOLAS and IMO requirements, including the supervision on deck by an officer.”

If such declaration is not forthcoming, or the pilot/pilot launch crew detect that the ladder is not fit for purpose, it is recommended that the transfer should not take place and the ship be directed to safe anchorage or holding position until a suitable pilot boarding arrangements can be provided.

Section 7 of the 1987 Act allows for a range of circumstances to be accommodated by the pilotage directions. They may specify:

- the area and conditions in which a direction applies

- circumstances in which special arrangements might apply

- procedures in the event of a pilot not being available (such as in adverse whether making boarding or landing unsafe)

- different boarding and landing positions for different situations.

All of these must be identified in the Risk Assessment and reflected in the directions.

4.5.16 Waiving directions