Competition document: Defence People Innovation Challenge

Updated 9 April 2018

1. Introduction

This Defence and Security Accelerator (DASA) competition seeks innovative solutions to how the Ministry of Defence (MOD) manages our people, both military and civilian. Building on the UK’s long tradition for developing effective, highly skilled Armed Forces and civilian workforce, we strongly believe in continuous improvement, and identifying and adopting new ideas, technologies and processes from other sectors.

The Defence People innovation challenge will focus on the following 5 themes which we consider offer the greatest scope for innovation and direct benefit to the management of people in the MOD:

-

Challenge 1 - recruitment

-

Challenge 2 - skills and training

-

Challenge 3 - retention

-

Challenge 4 - motivating the workforce

-

Challenge 5 - rehabilitation within the workforce

2. Background

In September 2016, the Defence Secretary launched the Defence Innovation Initiative, which acknowledged that we needed a new approach to innovation to maintain our military advantage. It also recognised that it’s the private sector, not Government, that drives today’s rapid pace of technological, social and cultural change.

People are central to Defence capabilities and are core to delivering Defence outputs. MOD employs 195,520 regular military and civilian staff and 32,240 Reserves. We rely on their skills, commitment and professionalism and place heavy demands on them. Recruiting, training and retaining the right mix of capable and motivated people is essential to success both on operations and at home and is one of the MOD’s major risks. A detailed discussion of this and the delivery of Defence outputs is contained in a recent National Audit Office publication A Short Guide to the Ministry of Defence.

Spending on Defence staff also accounted for around 30% (£10.3 billion) of the £36 billion Defence spending in 2016-17, and we must continually keep our costs and activities under review to ensure that the best result is achieved with the resources available. This includes exploring all opportunities to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of our people and the supporting processes, behaviours and cultures.

2.1 The role of people in Defence

People play an especially important role in delivering Defence outputs, as explained in paragraphs 2.19 and 2.20 of MOD’s Joint Concept Note, Future Force Concept, and is one that demands careful consideration when adopting, or adapting, new approaches. We know that emerging technologies including industrial robots, artificial intelligence, and machine learning are advancing at a rapid pace. Intelligent machines can support human decision-making by delivering advanced analytical power, and we are interested in how these might apply to our challenge.

The increasing pace and scale of technological change will have a continued and significant impact on the workforce. In the future the skills required, the ways of working and the way that the workforce (Armed Forces, Civil Service and contractors) connects with the MOD and the communities within it will fundamentally change.

While there are many benefits from advances in technology, it will never replace the human capability and capacity to create, innovate, and make judgements. Machines will never replace the human need for emotional connection, which is a key component in working life. We need to be better equipped to understand the implications of emerging technologies on the residual skills required to plan and embed a culture of lifelong learning.

Furthermore human qualities such as ingenuity and intuition will remain at the heart of mission success. Value-based decisions that require moral and ethical judgment are likely to remain a human endeavour for the foreseeable future in Defence.

2.2 Competition scope

The MOD has a lot in common with other large and complex organisations. For example we deal with a common set of challenges when managing people and there are many similarities in how we think about leading, managing and using our people.

When considering Defence as a business, many of the basics are the same in that we need to:

- attract and recruit a workforce or services

- train it to function

- equip it appropriately

- keep it motivated and sustained

- maximise its role in achieving productivity (this means different things dependent on role)

We must also positively manage those who leave the Services to provide them with the best possible start in their future careers after they’ve left the MOD and to recognise that we may also have to call on their skills and experience in the future.

The MOD has adopted a ‘Whole Force Approach’, which means our workforce comprises a mix of regular and reserve military forces, MOD civilians and contractors. We aim to get the most cost‑effective balance between the various groups of staff involved in Defence activities.

This competition is looking to bring innovative thinking to current issues, to the benefit of those developing and working on our people challenges now. It’s being launched alongside a range of complex change projects already underway in MOD (through the Armed Forces People Programme), and within the Royal Navy/Royal Marines, Army, Royal Air Force, Joint Forces Command and the Civil Service.

These include, but are not limited to:

- New Employment Model (now complete)

- New Joiner Offer

- Flexible Engagement System

- The Enterprise Approach (EA) - part of the wider Armed Forces People Programme and is a concept for an employment model designed to tackle shortages in critical skills identified by Defence. It will be based on collaborative arrangements between Defence and commercial partners to generate and share Suitably Qualified and Experienced Personnel (SQEP)

We know that we don’t have all the answers, so we’re seeking to identify ideas from the marketplace that will make Defence think and act differently and respond better to challenges and seize opportunities that we might otherwise miss.To maximise success we want to encourage proposals which address the challenges and consider how to integrate and exploit the benefits within current Defence structures, ways of working and processes.

We also want to encourage collaborative working amongst organisations with potential solutions to make best use of their experience of relevant people practices and novel enabling technology.

We’re committed to trying out those proposals that offer a real alternative and a step change in outcomes.

3. People Challenges

The scale and complexity of Defence People demands an open and flexible approach to potential solutions.The competition is based on 5 challenges but these shouldn’t be viewed as rigid, single themes which are mutually exclusive. We recognise that the concepts, processes, practices and technology which could deliver solutions are likely to address several of the challenges.Your proposal must meet at least one of the challenges, but we’d welcome bids that could address more than one.

Challenge 1: recruitment

In this challenge we’re looking for solutions that will help Defence to recruit the right mix of capable and motivated people – to recruit the right people.

The enduring issue for Defence is to make sure that across all parts of the Armed Forces and Civil Service, we have enough appropriately skilled people to meet our needs. This means we need to be able to recruit people who want to be part of a very specific way of life against a background of changing social norms and demographic pressures. Finding sufficient people and recruiting them into Defence at the right volume, and pace, continues to be challenging. To give you an idea of the scope of this issue, in 2017 15,300 people left the Armed Forces and 13,040 joined. Further detail about UK Armed Forces Personnel Statistics can be found here.

We face significant economic, employment, social and demographic challenges. These include: * a forecasted decline in the 16-25-year-old population * a shortage of individuals with Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) skills * security and nationality restrictions which further reduce the recruiting pool

Over recent years a shortfall in recruitment and higher than planned numbers leaving has left the Armed Forces with some significant strength deficits. As of 01 January 2018, the shortfalls were: Royal Navy/Royal Marines 3.7%, Army 6.3% and Royal Air Force 5.9%. Within these overall figures there are specific critical skills shortages in some engineering, logistics, intelligence and aircrew roles. Similarly, in the Civil Service there are skill shortages in contract, delivery and project and programme management roles.

The Armed Forces’ recruiting pipelines take a potential recruit from the ‘attract’ stage (for example marketing and outreach in national or targeted campaigns) through to initial training. The process applies a set of criteria and assessments to applicants meaning only those who are eligible to join the Armed Forces are accepted into training. The criteria, checks and assessments include educational qualifications, nationality, medical screening, fitness assessment, security vetting and aptitude tests. Much of the process is online and requires the creation of an account and the submission of large amounts of information, including proof of qualifications with coordination between various parties, for example local Armed Forces Careers Offices and medical assessment bookings.

The Services (Royal Navy/Royal Marines, Army and Royal Air Force) are already tackling many of the issues associated with the recruiting process. However, that doesn’t mean there aren’t other opportunities to further improve things using this competition. The goal in all cases is to ensure that candidates can complete all their required inputs quickly and accurately and that they feel motivated and engaged throughout the process of recruiting and initial training.

It’s important that each of the Services can explore and engage with potential recruits to make sure that they’re aware of all the options for service and employment that are available. Converting an individual’s interest into an informed career choice is particularly important. Similarly, there are several projects which are actively seeking to reduce the time taken from a firm expression of interest by an individual, through their recruitment into training and service. The Royal Navy has had some success with this in specific trades, and all 3 Services are interested in how this could be developed further and possibly scaled-up.

There are also other methods by which individuals can, and do, enter the Armed Forces. Those with previous service and suitable skills can return to full-time service. Members of the Reserve Force can also transfer to regular service and vice versa. The Armed Forces also have around 1.8% of our Civil Service staff who are members of the Reserve Forces and others who have previous military service and are classed as veterans. We also need to ensure we can manage and support this kind of flow of experience and knowledge.

In 2015 the MOD committed to reducing the size of its civilian workforce by the year 2020. This means that the future MOD Civil Service will need to be more agile and have different operating models to deliver its services whilst meeting individual and corporate aspirations. It will also need to grow capability quickly in certain areas. These include digital skills, cyber, intelligence, STEM and the human residual skills (for example judgement, ethics and moral decision making) resulting from advances in technology. The end-to-end civilian recruitment process can take a long time and currently potential candidates often don’t have a realistic preview of what it is like to work in MOD or of the wider opportunities available.

To ensure MOD attracts the very best to the Civil Service, we’ll need to widen the pool that we recruit from. The MOD needs to increase the mix of people from different sectors of the economy and society to ensure that we benefit from best-practice and improve the quality of services delivered to the public. Whilst female representation of MOD civilian personnel has increased to 42% and Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) representation has increased by 0.6% to 4.6% between October 2013 and October 2017, more can be done to make MOD more representative of the wider Civil Service and the nation we serve.

In this challenge we’re looking for solutions that will:

- increase attraction of suitable applicants from under-represented parts of society

- increase attraction of suitable applicants from under-represented professional groups

- minimise time and resources spent processing unsuitable candidates

- simplify, streamline and optimise Armed Forces recruitment without introducing unintended risk (for example by compromising security checks or lowering final output standards from basic training)

- improve our return on investment throughout initial and subsequent training

- exploit modern technology to improve the applicant experience through attraction, “onboarding” and subsequent training

- exploit current management information and supporting systems better

Factors to consider in your proposal:

- is our recruiting approach effective in terms of how we select, assess and identify suitable individuals? Is Defence focussing on the right criteria for example prioritising education level over potential and organisational or cultural fit

- how does Defence attract future talent, appear relevant and appeal to a broader workforce to generate a more diverse and inclusive workforce?

- could an improved approach to data analytics help Defence understand its resourcing requirements? This could include development of better means of representing existing data to inform recruitment planning and delivery?

- how could Defence better access skills and move towards a system that allows for more entry at a senior or experience hire level (for example accelerated apprenticeships, specific technical skills)?

- how can Defence better target limited recruiting resources to more effectively reach potential candidates through a structured and co-ordinated strategic communications campaign using digital data? Consideration should also be given to how to integrate any ideas with existing larger scale programmes

- how can Defence improve its candidate experience, reducing the time individuals spend in the recruiting pipeline, and provide an engaging experience which enhances the Armed Forces reputation?

Challenge 2: skills and training

In this challenge, we are looking for solutions which will provide assurance that our workforce is suitably knowledgeable, skilled and experienced to meet our needs, both today and in the future. This challenge is all about our people’s skills.

As we move forward, our approach to skills must remove any artificial boundaries or differences, within and between the separate Services, the Civil Service and those elements of the Defence Industry who need similar skills. We accept there are some fundamental differences between these areas, and want to see a future training endeavour that is “Whole Force by Design” across the areas of shared enterprise; we should strive for similarity and not allow our approach to be constrained, or defined, by any differences.

Whilst the terms ‘training’ and ‘education’ can be used interchangeably, the term ‘training’ is sometimes used to avoid repetition. In these instances, ‘training’ encompasses any training, education, learning or development, both individual and collective, which is designed to meet a clearly defined training requirement.

Armed Forces individual training

In this context, individual training is focused on the person and has evolved into an approach that provides militarisation (the induction process - initial training), professional or career training (which prepares an individual with the skills necessary for success in the next stage of their career) and task specific training (which provides the individual with the deep specialist skills required for their next assignment or role).

Approximately 13,000 Regular service personnel and 6,000 Reservists join the Armed Forces and start training each year. Each service has a different training journey with areas of clear similarity and obvious differences. These are largely shaped by the needs of their intended operating environment (Sea, Land or Air). Given their immediate command and leadership roles, Officers’ training is significantly different from that provided to the non-commissioned ranks.

Professional or task specific training provides scope for individual (training the novice) and team learning (training a “team of novices”). The former can be set at a pace which accommodates any prior experience or learning and repetition can be avoided. If this approach is adopted, then a different approach to planning and training execution may well be required. The needs of the individual, rather than the convenience and ease of planning for the class/cohort, would define the critical path for planning purposes. Once in the workplace, the novice skills can be refined and as experience grows the individual can be assessed to confirm their level of competence. This competence needs to be refreshed and updated which is achieved through continuation training.

These formal training interventions are complemented by ongoing personal development, which is the education, training and experience that enhances professional development and promotes personal motivation. It may not directly contribute to an individual’s ability to perform better in current or future employment but it is the acquisition of new knowledge, skills and experience that add to an individual’s overall capabilities as a person. It is devised by the individual, but can be exploited to the benefit of the employing Service and/or Defence. This is especially the case with Further and Higher Education.

Armed Force collective training

Combat effectiveness is achieved at the collective level, and often involves people and equipment operating effectively as one. At the most basic level we “equip the man” by providing a soldier with a weapon. At the extreme we “man the equipment”, which is most obvious in ships, submarines and aircraft. Collective training is when we optimise performance and start to train at the team level all the way through to complex training exercises, involving all 3 Services and often combined with forces from other nations.Training for these complex operational tasks can be very expensive particularly when fuel and equipment costs are factored in for live training environments. ‘Traditional’ synthetic environments tend to also come with a high price. Training for every eventuality may not be the most efficient way to make sure that the right knowledge, skills and experience exist in the right place at the right time.

Civil Service training

Training in the Civil Service is based on individual development needs and training required for undertaking a role. In its most basic terms, training for Civil Servants in MOD is broken down into four categories: Mandatory Training, Personal Effectiveness, Leadership and Management, and Profession-Specific Training. Learning under each of these categories can be accessed through our two main providers, Civil Service Learning and the Defence Academy. This training is individually focussed, complex and largely outsourced.

Defence has the challenge of developing the required skills as efficiently as possible as well as supporting individuals to achieve their potential in 3 main areas of interest:

- improve the speed at which skills are acquired (speed to skill) across Defence by exploiting new technologies (including Artificial Intelligence (AI)) and learning methodologies, and through smarter planning and delivery that makes best use of scarce resource

- strike the right balance between professional and personal development, encouraging the former and optimising the timing and effect of the latter. The approach must improve individual capability and deliver better productivity through smarter, shorter training interventions

- design equipment that minimises the demand for skills and thus training. Exploiting the potential of AI and automation

In this challenge we’re looking for solutions that will:

- enable us to reduce the cost of developing new skills and knowledge in our people

- enable us to produce resource optimised plans that make optimum use of all strands of resource (trainers, trainees, equipment, infrastructure, time and cost)

- reduce skills and knowledge fade throughout a career

- improve access to niche/critical skills for the future

- improve the capability of Defence people to innovate and adapt

- promote a learning culture that encourages learning from experience

- leverage training already provided elsewhere in the economy

- improve productivity in the workforce by developing skills through individual learning throughout a career and promoting continuous adult learning across the whole workforce

- equip the MOD to understand the implications of emerging technologies on our residual human skills (for example ethics, moral, judgement) and how to incorporate these impacts in workforce planning

Factors to consider in your proposal:

- how can Defence reduce its training overhead by adapting a more modular, needs based approach to training?

- to what extent could different technologies and simulated environments support a more responsive, efficient training machine?

- how do we create an innovative mind-set amongst our people?

- how do we encourage leaders and managers to lead organisational-learning and champion talent development?

- how do we enable the identification of knowledge, skills and abilities (elements of human capital) that would contribute to the delivery of military training, where that capital has not been developed in the individual by means of military training? It may be that an individual has an appropriate inherent ability/affinity or has developed knowledge or skills through external training or interest

- how do we encourage leaders and managers to “role model” organisational learning and champion the development of talent?

Challenge 3: retention

In this challenge we’re looking for solutions that will help us to retain the skills and experience of our people for longer.

Retaining our people, especially those we have trained extensively, making them commercially attractive, is important for both capability and value-for-money. Our turnover in some areas is higher than we would like and doesn’t always respond quickly to our interventions. We have a growing body of evidence and insight which helps us to better understand our workforce, but it’s likely that there’s more we could do to use the data we already have, and more we could gather, to better inform and so improve our people policies and decision making.

As an organisation which relies on building knowledge, skills and experience from the “bottom up”, the Armed Forces benefits from a steady turnover of people joining and refreshing the organisation. Many will eventually leave and take their skills elsewhere into the economy. Typically, around 4-5% choose to leave the Armed Forces each year with another 3-5% leaving for other reasons (including end of contract and health). Some people join only wanting a short career, leaving after 4-5 years, while others want longer term careers with the opportunity to progress (12-20 years). This model has served the Armed Forces well but relies on a balance between sustained regular inflow at junior ranks and the retention of individuals with the right knowledge, skills and experience in more senior roles. When this balance is upset (where there’s insufficient intake or high levels of outflow) the Services can struggle to react to the changes causing shortfalls.

Retaining people that the Services believe have the right knowledge, skills and experience to maintain the capabilities of the Armed Forces delivers a better return for the investment made in training and development. It’s also healthy for the individual and the organisation for people to leave before the end of their planned engagement as their ambitions and circumstances change – but this needs to be carefully managed for the benefit of the organisation and the individual.

The reasons for choosing to leave early fall into two broad categories; the effect that Service life has on the individual (“push” factors) and wider life and market forces (“pull” factors). The main “push” factors cited when people leave are: impact of Service life on family and personal life, spouse or partner’s career, Service morale, individual’s morale, lack of current job satisfaction and dissatisfaction with overall career/promotion prospects. The most common ‘pull’ factors are: opportunities outside the Service, seeking fresh challenges and the desire to live in own home or settle in one area.

In the Civil Service, there a number of challenges with retention and identifying where critical skills are held by individuals within the workforce is a concern. It’s particularly difficult to track those people to make best use of their talents and consequently risk losing them. There’s a broader reward offer above that of salary and bonus with a total benefits package that includes flexible working, learning and development, access to employee discount schemes and other attractive policies. These benefits aren’t always well understood and improving people’s understanding of them (and access to them) could be used to improve retention.

We’re interested in how we can retain the key skills we need within the organisation, both from a Whole Force perspective as well as in our key areas of shortages.

In this challenge we’re looking for solutions that will:

- increase Defence’s systemic understanding of retention of the Whole Force, providing for the systematic mechanism(s) to gather honest data periodically that can inform the development of policy enabling us to increase the average length of time that people work for us

- increase our ability to access niche military skills after people leave regular service (for example through Reserve Forces / Full Time Reserve Service)

- strengthen management information tools to increase the data we have on those people with critical skills to better manage their career and identify opportunities to align current efforts addressing voluntary outflow and retention into a unified approach

- increase people’s understanding of the total-reward offered in Defence and enable us to better communicate this to individuals

- identify and assess the behavioural implications of changes to different elements of remuneration (pay, financial retention incentives and recruitment and retention packages) and any non-remunerative elements of the employment offer and how they interrelate on the decisions of service personnel and future joiners relating to careers in the Armed Forces

Factors to consider in your proposal:

- how does Defence best balance expectations against the reality of employment?

- to what extent can Defence seek to better differentiate it’s offer to allow for more personal choice?

- how does Defence undertake workforce analysis to understand what cohorts of personnel are the highest priority to retain?

- how does Defence understand and cater for what new generations coming in to the labour market want from a career in the MOD?

- how should Defence determine how it values differing skill sets (for example critical skills, technicians, aviators) and how should this affect specialist pay supplements/financial incentives?

- solutions must also take account of the facts that people join one of the 3 Services, not ‘Defence’ as such

Challenge 4: motivating the workforce

In this challenge, we’re looking for solutions that will motivate and increase our people’s engagement and leadership skills, enabling them to actively contribute to our goals.

The MOD uses the annual continuous attitude surveys: Regular (Full Time) (AFCAS), Reserves (Part Time) (RESCAS), Civilians (CAS) and military families (FAMCAS) to understand the different attitudes of MOD personnel.

Statistics from AFCAS are used by both internal MOD teams and external bodies to inform the development of policy and measure the impact of decisions affecting personnel, including major programmes such as the Armed Forces Covenant and New Employment Model. Findings from AFCAS 2017 show that satisfaction with Service life has fallen steadily by about a third since 2009. Since 2016 there has been a decline in personnel agreeing that their Service motivates them to achieve their Services objectives. This follows a generally decreasing trend since 2011.

We also survey our civilian workforce annually to assess employee engagement through the MOD People Survey. This provides all Civil Servants, contractors, and military line managers of civilian staff the opportunity to have a say about what it’s like to work in Defence. Our 2017 survey showed that the MOD scored positively on questions that asked about individuals’ interest in their work and whether they felt they had the skills to do their job effectively. However, the results also showed that staff felt that change wasn’t managed well and that it wasn’t usually for the better. There was an increase on questions about senior leader visibility and consistency with the MOD’s values however, the leadership and managing change score remained relatively low at 31%. A recurring theme was the concern around the pay and benefits package in the Department. There were also concerns around the question “I think it is safe to challenge the way things are done in the MOD”. This needs to change as the way people interact and feel about work changes.

The survey results suggest that the MOD needs to increase trust and confidence in leaders and provide mechanisms to increase meaningful communications at all levels of the organisation to increase engagement. This aligns with other, more limited internal research revealing a disconnect between senior leadership and Service personnel, the latter reporting that an understanding of life ‘on the ground’ is not evident in internal messaging.

In this challenge we’re looking for solutions that will:

- increase trust and confidence in the leadership at all levels of the organisation

- reduce the time it takes us to identify issues, to enable the organisation to enact strategies to improving motivation

- increase the effectiveness of our communications, in particular, our ability to understand and communicate with “hard-to-reach” groups (for example junior ranks and staff, deployed military personnel)

- increase our people’s sense of well-being and resilience

- strengthen the psychological contract from the initial application through to the end of service and beyond

- provide performance metrics for understanding the effect of poor motivation

- improve understanding of the impact of change and efficiency savings on motivation and performance

- help us to understand how we can develop more effective feedback at all levels of the organisation

- provide a responsive method to inform evidence based practice, gaining the views and experiences of our workforce to inform, monitor and evaluate policy

Factors to consider in your proposal:

- how do we communicate with our people using channels and methods that resonate with them, especially with hard-to-reach groups (for example junior ranks, deployed personnel)? Are we able to adequately measure the impact our communications have on their understanding?

- how do we better understand what the key motivators of our people are to target the employment offer

- how do we get regular feedback from our personnel to maintain a health-check on the morale of the organisation?

- how can we provide feedback to senior leaders which encourages and supports a more “360 degree” approach to leadership and engagement across the work force?

- how can we accelerate career progression of talented individuals in what has traditionally been a very rigid and rule based system?

- how can we reduce change fatigue in an organisation that is continually evolving?

- how can we better match personal motivations with Service needs through innovative career management?

- how do we collate / understand the perceptions and attitudes of our workforce in ‘real-time’ to understand organisational climate?

Challenge 5: rehabilitation within the workforce

Promoting, sustaining and restoring the optimal physical and mental wellbeing of Service personnel is a vital component in Defence’s ability to maximise the number of people fit for task.

This challenge is therefore solely focussed on Armed Forces personnel.

The complex nature of current and future operating environments provide significant occupational and environmental challenges to Defence personnel and the issues in providing the requisite supporting services continues to evolve.

One of the greatest threats is the impact of musculoskeletal injury (MSKI) which is recognised as the leading cause of medical discharge (61% of those medically discharged per annum) from both initial training and in particular the Army more generally. MSKI is estimated to cost £86 million per annum to the Army and predicted to be £1.02 billion over 15 years. The second principal cause of discharge is mental ill health (14% RN, 22% Army, 30% RAF medical discharges) and in addition to the financial costs, the moral responsibility to reduce these injuries and ill-health is high. Given the impact of injury and ill-health on the ability of an individual to deploy on operations, their combat effectiveness, and the time and cost in treating and rehabilitating personnel, understanding how to effectively mitigate against this risk is crucial for achieving a healthy and operationally deployable workforce.

In this challenge we’re looking for solutions that will:

- seek to prevent MSKI in service personnel improving physical training across the full range of training activities at both an individual and cohort level. Solutions should also seek to provide analytical insight into physiological training data to enable optimisation and individualisation of training programmes to avoid/reduce injury. Solutions could include the use of telemetry to inform and optimise strength and conditioning practices in military training

- support clinical outcomes during MSKI rehabilitation programmes by optimising individuals exercise based rehabilitation programmes and treatment regimes

- seek to increase the physical, psychological and emotional resilience of individuals and the social resilience of teams, in order to reduce the risk of MSKI and mental ill-health and enhance rehabilitation

- promote and enhance the long-term adoption of health behavioural changes (smoking, nutrition, hydration, sleep and so on) that are current risk factors for poor health

Factors to consider in your proposal:

- that we don’t yet understand the full spectrum of occupational risk of MSKI, which are not limited to physical training, and solutions may also enable an improved understanding

- solutions may have utility in both prevention and rehabilitation of physical and mental illness and injury

- MOD isn’t looking for solutions to increase organisational, family or economic resilience

4. What we don’t want for these challenges

For this competition we’re not interested in proposals for:

- consultancy

- paper-based studies or literature reviews

- proposals without clear detail on the metrics which will be used to define the success of the solution

- solutions which require unreasonable volumes of data

- incremental improvements

- projects that only offer a written report – we’re looking for a practical demonstration

- projects that can’t demonstrate feasibility within the timescale

- solutions that don’t offer significant benefit to Defence

5. Competition Design

The aim of this Defence People innovation challenge is to achieve exploitation of successful proposals, within 3 years, across all 5 challenges. Up to £3 million will be available for this competition in the first year with the potential for further funding available in future years.

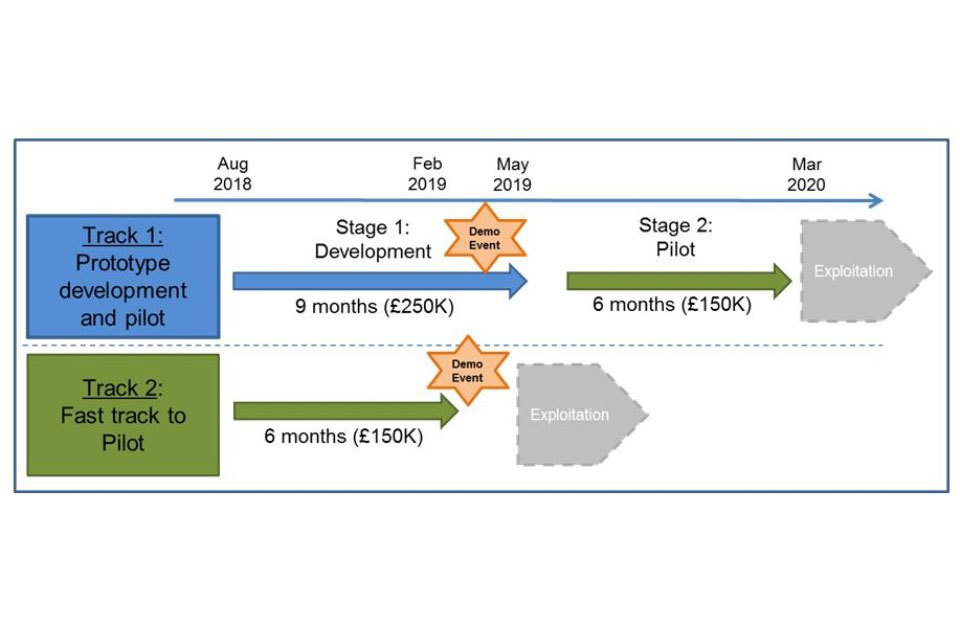

To achieve greater pace while providing the opportunity for smaller companies and lower maturity solutions to participate, we will be using a 2-track, outcome-focussed approach. Proposals can be submitted against any of the 5 challenges into one of the 2 tracks. Bidders can submit more than one proposal into one or both tracks but each proposal must be clearly distinct and a standalone bid as each will be assessed individually.

We also want to encourage collaborative working amongst organisations with potential solutions to make best use of their experience of relevant people practices and novel enabling technology.

Track 1: Prototype development and pilot

This track will have 2 stages. Proposals into this track can be at any stage of development. However, they need to show evidence of how an exploitable outcome could be achieved within 3 years.

For stage 1 of track 1, proposals should aim to demonstrate development of a minimum viable product status (normally Technology Readiness Level (TRL) 5) within 9 months. Proposals that are successful at stage 1 will then be invited to bid into stage 2 of the competition. Stage 2 will be for funding to pilot the capability developed in the stage 1 project in a representative operating environment.

Proposals submitted at stage 1 should not exceed £250,000. At the end of stage 1 winners will be required to attend a demonstration event to validate the success of the development undertaken and provide evidence that the proposal remains on track to deliver the high levels of value for the MOD envisaged at the outset. This demonstration event will also maximise exploitation through MOD and wider government.

Only track 1, stage 1 winners will be able to bid for follow on funding in track 1, stage 2. Stage 2 proposals will be no longer than 6 months from the start of the contract and should not exceed £150,000. Your proposal should provide a recommendation of preferred host for the pilot, MOD, Joint Forces Command or one of Royal Navy, Army or Royal Air Force, and this will be agreed as part of the selection process for stage 2.

More details on stage 2 submission process will be provided to successful track 1 stage 1 applicants before stage 2 begins.

Track 2: Fast track to pilot

Proposals into this track are invited which are ready to be piloted in a representative operating environment. The proposal should provide a recommendation of preferred host for the pilot, MOD, Joint Forces Command or one of Royal Navy, Army or Royal Air Force, and this will be agreed as part of the selection process.

Track 2 proposals will be no longer than 6 months from the start of the contract and should not exceed £150,000.

Figure 1 shows how the 2-track approach will work.

Figure 1: The competition process

5.1 Hosting support for pilot projects

If your proposal offers an information and communication technology (ICT) solution and you’re unable to provide hosted provision that meets our security requirements, we’ll work with you to provide an environment that enables you to manage the solution and grant secure access for the duration of the pilot.

We won’t offer any on-premises capability or service, and both supplier and user access will be managed remotely. Solutions will need to demonstrate how they meet security, General Data Protection Regulation(GDPR) and access requirements in consultation with the MOD.

If your proposal relies on extant data, you must clearly define your data requirements in your proposal. The feasibility of providing this data will be considered as part of the assessment process. Your proposal should also include details of any requirements for any other Government furnished assets (GFA).

5.2 Innovation maturity

We use TRLs to assess and describe innovation maturity. We understand that TRLs are not a perfect measure of innovation maturity however they are widely understood and used by industry and academia. We anticipate that TRLs will be an adequate means of assessing the maturity for all proposals received in response to this competition. Note that, although a commercial solution may already be in use in another market, we assume that it returns to a lower TRL for a Defence context until success is demonstrated in a representative operational environment.

5.3 Exploitation

This DASA competition will provide the opportunity to expose your idea to a wide MOD stakeholder group including end-users and procurement agencies with the aim of accelerating successful projects into the next stage of their exploitation pathway.

It’s important that your proposal demonstrates how your idea will deliver significant change in Defence people capability and how it could be integrated with current processes and programmes. Your proposal should include how the product will be matured in a representative operational environment and how you plan to demonstrate its value by means of a business or economic case to the MOD in addition to a predicted TRL. Your proposal should consider potential collaboration and engagement with other suppliers where possible.

During the competition the DASA team will seek to engage the right people at the right time and bring end-users into the process early in order to help shape development. You will be heavily involved in creating an enterprise that can identify and manage risks to exploitation and to identify the scale of change required by MOD to implement your technology. This will create the conditions to enable an informed decision to be made on the onward exploitation of your idea.

You should also consider whether your product has additional exploitation routes outside of the MOD such as through a Defence Prime, commercial organisation or export.

5.4 The Competition Process

It’s important for you to read the Accelerator terms and conditions. We reserve the right to reject proposals if they are deemed to not meet the challenge.

Your proposal will then be assessed using the DASA assessment process. All the assessors will be trained to the same standard and will be drawn from a pool of technical experts and end-users in the MOD, and may also include independent subject matter experts from industry contracted by MOD.

Each proposal will undergo assessment with the output scrutinised at Decision Conference to select proposals worthy of funding. If you are selected by the Decision Conference you should be ready to verbally pitch your proposal, in confidence, at the competition Concept Selection event which will take place shortly after. The panel at the event will be senior individuals within MOD.

For this competition we will be using the Short Form Contract (SFC). This is a MOD initiative that has been designed to ensure Small-to-Medium Enterprises (SMEs), as well as Universities and larger organisations have access to less complex contracting processes.

All successfully funded projects will be allocated a Technical Partner. They will provide advice and guidance and also an interface between the MOD stakeholder communities. Technical Partners will be supported by DASA Innovation Partners.

Deliverables from contracts will be made available to Technical Partners and relevant UK MOD and wider government stakeholders.

All winners will be expected to demonstrate their solutions at the appropriate demonstration opportunity for their project or a demonstration day. In your proposal you should cost your attendance at the demonstration event. DASA may also choose to invite other suppliers to these events to support wider collaboration.

5. MOD Research Ethics Committee

There is a significant chance of proposed solutions requiring MOD ethical scrutiny, especially if human subjects are to be involved in any demonstrations, assessments and experiments. All research involving human participation conducted or sponsored by any government department is subject to ethical review under procedures outlined in Joint Service Publication 536 ‘Ministry of Defence Policy for Research Involving Human Participants’, irrespective of any separate ethical procedures (e.g. from universities or other organisations). This ensures that acceptable ethical standards are met, upheld and recorded, adhering to nationally and internationally accepted principles and guidance.

The following definitions explain the areas of research that require approval:

- clinical: conducting research on a human participant, including (but not limited to) administering substances, taking blood or urine samples, removing biological tissue, radiological investigations, or obtaining responses to an imposed stress or experimental situation

- non-clinical: conducting research to collect data on an identifiable individual’s behaviour, either directly or indirectly (such as by questionnaire or observation)

All proposals must declare if there are potential ethical issues. Securing ethical approval through this process can take up to 3 months.

Read more on the MOD Research Ethics Committee.

If you think that your proposal may require ethical approval, please ensure that you adopt an approach in your submission as follows:

- milestone 1: gaining ethics approval for the project, including delivery of the research protocols (the protocol will need to be detailed by completing the ethics application form)

- milestone 2: proposed research that will be carried out subject to gaining ethics approval (optional phases to be formally invoked, where appropriate)

A contractual break point must be included after milestone 1.

The requirement for ethical approval isn’t a barrier to funding; proposals are assessed on technical merit and potential for exploitation. Successful proposals will be supported through the ethical review process, however an outline of your research methods must be included in your proposal to help this process.

6. Dates

| Competition Launch Event | 27 March 2018 |

| Competition closes | 16 May 2018 (midday) |

| Concept Selection Day (funding decisions made) | mid July 2018 |

| Contracting (Track 1 stage 1 and track 2) | mid August 2018 |

Track 1 Prototype development and pilot

| Stage 1 projects complete | May 2019 |

| Stage 1 demonstration event | TBC |

| Stage 2 competition opens | May 2019 |

| Stage 2 competition closes | July 2019 |

| Stage 2 ends | March 2020 |

| Demonstration activity | TBC |

Track 2 Pilot

| Projects complete | February 2019 |

| Demonstration event | TBC |

7. Queries and Help

While you’re preparing your proposals, you can contact us if you have any questions.

Technical queries about this competition should be sent to dasa-defencepeople@dstl.gov.uk

Capacity to answer these queries is limited in terms of volume and scope. Queries should be kept to a few simple questions or if provided with a short (few paragraphs) description of your proposal, the technical team will provide, without commitment or prejudice, broad yes/no answers. This query facility is not to be used for extensive technical discussions, detailed review of proposals or supporting the iterative development of ideas. There will also be opportunities to access members of the DASA team at the launch event and follow on webinar.

While all reasonable efforts will be made to answer queries, DASA reserves the right to impose management controls when higher than average volumes of queries or resource demands restrict fair access to all potential proposal submitters.

General queries should be sent directly to DASA at accelerator@dstl.gov.uk