Online targeting: Final report and recommendations

Published 4 February 2020

Foreword

Online targeting is a remarkable technological development. The ability to monitor our behaviour, see how we respond to different information and use that insight to influence what we see has transformed the internet, and impacted our society and the economy.

When technology develops very swiftly, there comes a moment when the implications of what is happening start to become clear. We are at such a moment with online targeting. A moment of recognition of the power of these systems and the potential dangers they pose.

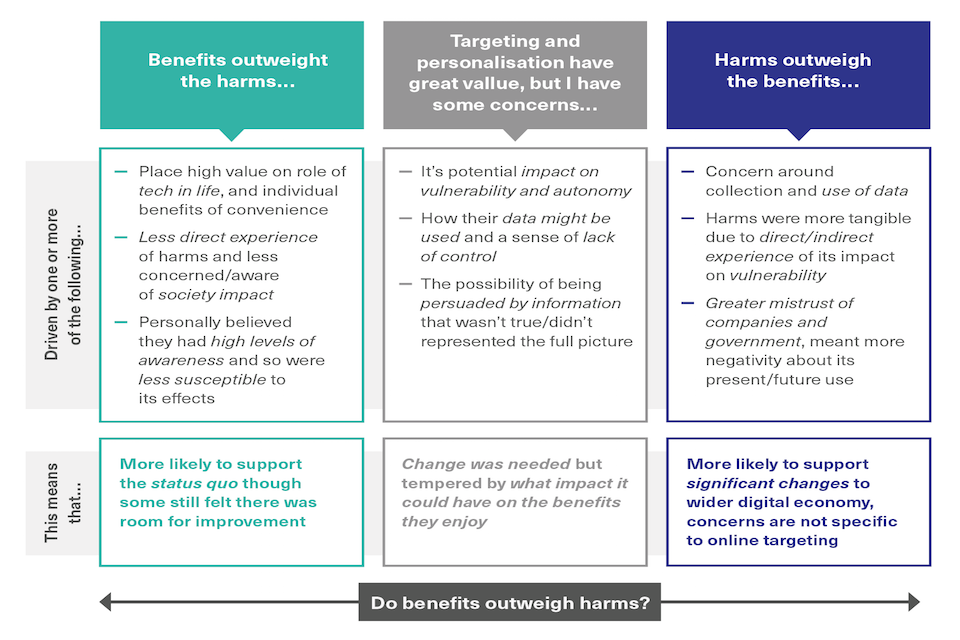

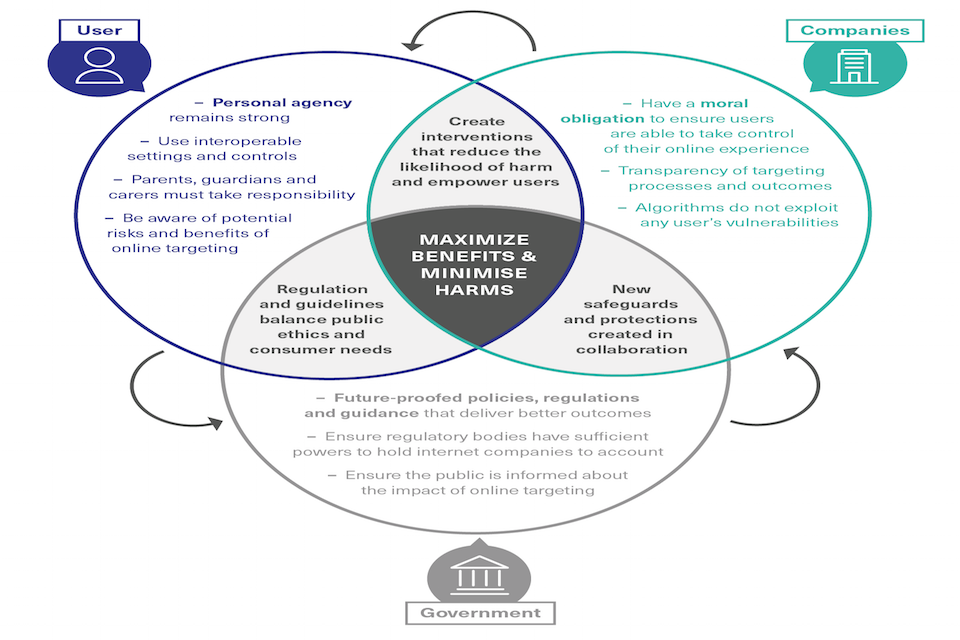

In considering how the UK should respond, our starting point was to understand public attitudes. What we found was an appreciation of the value of targeting but deep concern about the potential for people’s vulnerabilities to be exploited; an expectation that organisations using targeting systems should be held to account for harm they cause; and a desire to be able to exercise more control over the way they are targeted.

Most people do not want targeting stopped. But they do want to know that it is being done safely and ethically. And they want more control.

These are very reasonable desires. But that does not mean it is easy – or even possible – to accommodate them. In making our recommendations we are proposing actions that kickstart the process of working out how public expectations can best be met.

Some of it requires greater regulation – and that requires systemic and coordinated approaches that focus first on the areas of greatest concern – such as the impact of social media on mental health.

The world will be looking at the UK’s approach and it is vital that new internet regulation protects human rights such as freedom of expression and privacy.

But it also requires innovation: innovation in the way that we regulate and innovation in the way the targeting systems are built and operated. Our recommendations are designed to encourage both.

By emphasising the need for a regulator to have powers to investigate how targeting systems operate, we recognise that better understanding will lead to more effective and proportionate regulation.

Giving people more control over the way they are targeted is a more complex challenge. Tools to manage consent or to set preferences are clunky and unsatisfying. More radical solutions are harder to implement. We believe our recommendations can act as spur to innovation and new models of data management.

We have made three sets of recommendations to enable the UK to realise the potential of online targeting, while minimising the risk. First, new regulation to manage online harms that the government is planning to introduce should ensure that companies that operate online targeting systems are held to higher standards of accountability. Second, the operation of online targeting should be more transparent, so that society can better understand the impacts of these systems and policy responses can be built on robust evidence. Third, policy should seek to give people more information and control over the way they are targeted, so that such systems are better aligned to individual preferences.

These recommendations will help to build public trust over the long term, and enable our society and economy to benefit from online targeting. The UK has an opportunity to develop a world leading approach, and the CDEI looks forward to working with industry, civil society, policymakers, and regulators to achieve it.

Roger Taylor Chair, Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation

Executive summary

Data-driven online targeting is a new and powerful application of technology. Using machine learning, online targeting systems predict what content is most likely to interest people, and influence people to behave in a particular way.

Personalisation of users’ online experiences increases the useability of many aspects of the internet. It makes it easier for people to navigate an online world that otherwise contains an overwhelming volume of information. Without automated online targeting systems, many of the online services people have come to rely on would become harder to use.

Online targeting systems are used to promote content in social media feeds, recommend videos, target adverts, and personalise search engine results. Online targeting is already an important driver of economic value and is a core element of the business models of some of the world’s biggest companies. It enables individuals and organisations to find a bigger audience for their stories or point-of-view, and businesses to find new customers. Automated systems now make decisions about a significant proportion of the information seen by people online.

As the underlying technology continues to develop, online targeting will continue to grow in sophistication and it will be used in novel ways and for new purposes. There are already a number of services that help people make positive changes by tracking their health, diet or finances and use personalised information or nudges to influence their actions. There is significant potential for further innovation.

However, online targeting systems too often operate without sufficient transparency and accountability. The use of online targeting systems falls short of the OECD human-centred principles on AI (to which the UK has subscribed), which set standards for the ethical use of technology. Online targeting has been blamed for a number of harms. These include the erosion of autonomy and the exploitation of people’s vulnerabilities; potentially undermining democracy and society; and increased discrimination. The evidence for these claims is contested, but they have become prominent in public debate about the role of the internet and social media in society.

Online targeting has helped to put a handful of global online platform businesses in positions of enormous power to predict and influence behaviour. However, current mechanisms to hold them to account are inadequate. We have reviewed the powers of the existing regulators and conclude that enforcement of existing legislation and self-regulation cannot be relied on to meet public expectations of greater accountability.

The operation and impact of online targeting systems are opaque. Information about the impact of online targeting systems on people and society is difficult to obtain as much of the evidence base is held by major online platforms. This prevents the level of scrutiny required to robustly assess the impact of targeting systems on individuals and society, and helps to obscure accountability.

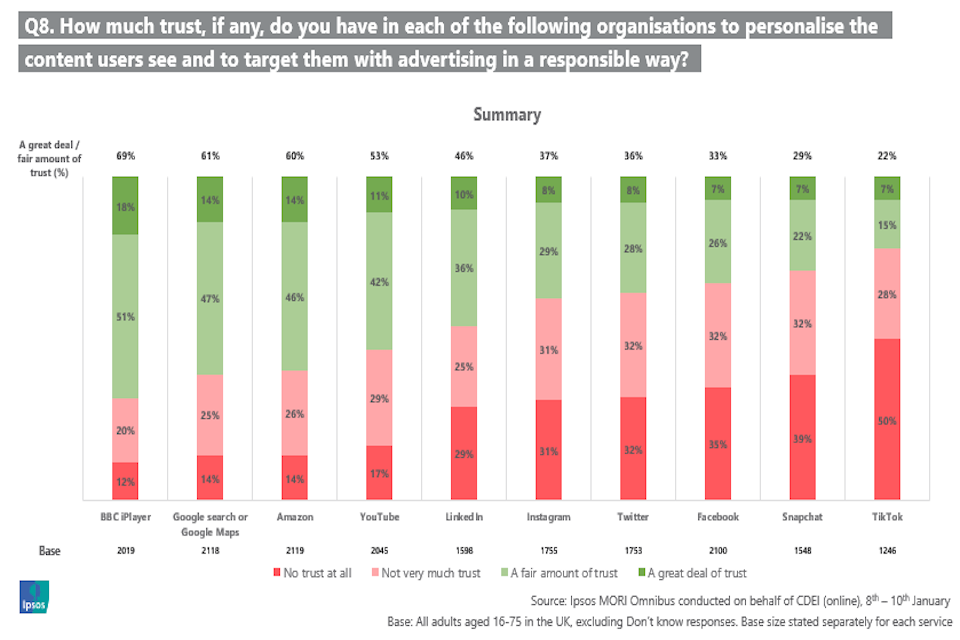

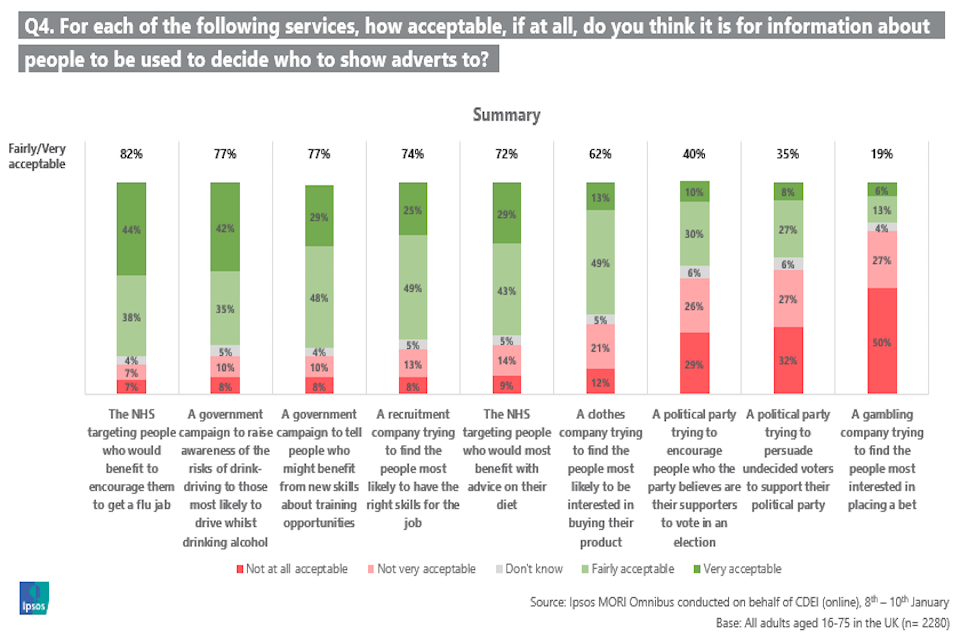

Our new research into public attitudes towards online targeting shows that people welcome the convenience these systems offer, but express concern when they learn about the systems’ prevalence, sophistication and impact. They are particularly concerned about the impact of online targeting on vulnerable people. People do not want targeting to be stopped. But they do want online targeting systems to operate to higher standards of accountability and transparency, and people want to have meaningful control over how they are targeted.

There is recognition from industry as well as the public that there are limits to self-regulation and the status quo is unsustainable. Now is the time for regulatory action that takes proportionate steps to increase accountability, transparency and user empowerment. We recommend a number of steps to address public trust over the longer term.

We do not propose any specific restrictions on online targeting. Instead we recommend that the regulatory regime is developed to promote responsibility and transparency and safeguard human rights by design. Regulators must be able to anticipate and respond to changes in technology, and seek to guide its positive development to be better aligned with people’s interests.

The government should strengthen regulatory oversight of organisations’ use of online targeting systems through its proposed online harms regulator, working closely with other regulators including the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO). The regulator should be required to increase accountability over online targeting through a code of practice. The code should require organisations to adopt standards of risk management, transparency and protection of people who may be vulnerable, so that they can be held to account for the impact of online targeting systems on users.

Regulation of online targeting should be developed to safeguard freedom of expression and privacy online, and to promote human rights-based international norms. The online harms regulator should have a statutory duty to protect and respect freedom of expression and privacy.

The regulator will need information gathering powers to assess whether platforms are operating in compliance with the code of practice, so that they can be held to account. In some cases external independent support will be needed to establish this. The regulator should have the power to require platforms to give independent experts secure access to their data to enable further testing of compliance with the code.

The regulator must use its powers in a proportionate way, recognising that the use of targeting can be low risk and to ensure responsible innovation can flourish. The regulator’s use of its powers should be subject to due process, with an established threshold for investigation, consultation with stakeholders, and a process under which the regulator’s findings can be appealed. The regulator must act at all times to protect privacy and commercial confidentiality. The online harms regulator should work with the ICO and the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) to develop formal coordination mechanisms to ensure regulation is coherent, consistent, and avoids duplication.

Online targeting systems may have a negative effect on mental health, for example as a possible factor in “internet addiction”. They could contribute to societal issues including radicalisation and the polarisation of political views. These are issues of significant public concern, where the risks of harm are poorly understood, but the potential impact too great to ignore. We recommend that the regulator facilitates independent academic research into issues of significant public interest, and that it has the power to require online platforms to give independent researchers secure access to their data. Without this, the regulator and other policymakers will not be able to develop evidence-based policy and identify best practice.

Platforms should be required to maintain online advertising archives, to provide transparency for types of personalised advertising that pose particular societal risks. These categories include politics, so that political claims can be seen and contested and to ensure that elections are not only fair but are seen to be fair; employment and other “opportunities”, where scrutiny is needed to ensure that online targeting does not lead to unlawful discrimination; and age-restricted products.

We recommend a number of steps to meet public expectations for more meaningful control over how users are targeted. This includes support for a new market in third party “data intermediaries”, which would enable users’ interests to be represented across multiple services, and new third party safety apps.

Our analysis of public attitudes shows that there is an expectation that the public sector should use online targeting to ensure that advice and services are delivered as effectively as possible. Clear standards for the ethical use of online targeting systems will encourage the public sector to have greater confidence in using these techniques.

Societies are in the early years of developing policy and regulatory responses to data-driven technologies like online targeting. It took over a century to develop a regulatory framework to respond to the impact of steam power. The UK must learn the lessons of the past. By focusing on building the evidence base for informed policymaking and creating the right incentives, the UK will be able to govern online targeting in a way that is both trustworthy and allows responsible, sustainable innovation to thrive.

Key recommendations

Accountability

The government’s new online harms regulator should be required to provide regulatory oversight of targeting:

- The regulator should take a “systemic” approach, with a code of practice to set standards, and require online platforms to assess and explain the impacts of their systems.

- To ensure compliance, the regulator needs information gathering powers. This should include the power to give independent experts secure access to platform data to undertake audits.

- The regulator’s duties should explicitly include protecting rights to freedom of expression and privacy.

- Regulation of online targeting should encompass all types of content, including advertising.

- The regulatory landscape should be coherent and efficient. The online harms regulator, ICO, and CMA should develop formal coordination mechanisms.

The government should develop a code for public sector use of online targeting to promote safe, trustworthy innovation in the delivery of personalised advice and support.

Transparency

- The regulator should have the power to require platforms to give independent researchers secure access to their data where this is needed for research of significant potential importance to public policy.

- Platforms should be required to host publicly accessible archives for online political advertising, “opportunity” advertising (jobs, credit and housing), and adverts for age-restricted products.

- The government should consider formal mechanisms for collaboration to tackle “coordinated inauthentic behaviour” on online platforms.

User empowerment

Regulation should encourage platforms to provide people with more information and control:

- We support the CMA’s proposed “Fairness by Design” duty on online platforms.

- The government’s plans for labels on online electoral adverts should make paid-for content easy to identify, and give users some basic information to show that the content they are seeing has been targeted at them.

- Regulators should increase coordination of their digital literacy campaigns. The emergence of “data intermediaries” could improve data governance and rebalance power towards users. Government and regulatory policy should support their development.

The CDEI would be pleased to support the UK government and regulators to help deliver our recommendations.

Introduction

About the CDEI

The adoption of data-driven technology affects every aspect of our society and its use is creating opportunities as well as new ethical challenges.

The Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation (CDEI) is an independent expert committee, led by a board of specialists, set up and tasked by the UK government to investigate and advise on how we maximise the benefits of these technologies.

Our goal is to create the conditions in which ethical innovation can thrive: an environment in which the public are confident their values are reflected in the way data-driven technology is developed and deployed; where we can trust that decisions informed by algorithms are fair; and where risks posed by innovation are identified and addressed.

More information about the CDEI can be found at www.gov.uk/cdei.

About this review

We have a unique mandate to make recommendations to the government drawing on expertise and perspectives from stakeholders across society. We provide advice for regulators and industry. This supports responsible innovation and helps build a strong, trustworthy system of governance. The government is required to consider and respond publicly to these recommendations.

In the October 2018 Budget,[footnote 1] the Chancellor announced that we would be exploring the use of data in shaping people’s online experiences. This review forms a key part of our 2019/2020 work programme.[footnote 2] It relates closely to several government workstreams, including the planned Online Harms Bill. It also relates to a number of high-profile regulatory activities, including the Competition and Markets Authority’s (CMA) market study into online platforms and digital advertising,[footnote 3] and the Information Commissioner’s Office’s (ICO) code of practice on age appropriate design for online services.[footnote 4]

This is the final report of the CDEI’s Review of Online Targeting and includes our first set of formal recommendations to the government.

Our focus

There are many applications of online targeting systems. We focus on the most prevalent, powerful and high-risk forms of online targeting: personalised advertising and content recommendation systems.

We focus on the issues that we have found are of greatest concern to the public, and where we assess there are significant regulatory gaps. We have looked in depth at the role online targeting plays in three areas: autonomy and vulnerability, democracy and society, and discrimination. Online targeting is closely related to competition policy and data rights, but we have focused less on these issues as they are being addressed by the CMA and ICO respectively.

Online targeting systems are used across the internet. They become more powerful at scale, when informed by the data of large numbers of users. This is put to greatest effect by major online platforms. Despite their powerful positions in society, these platforms operate with low levels of accountability and transparency. Our analysis of the regulatory environment demonstrates significant gaps in their regulatory oversight. Our analysis of public attitudes shows greatest concern and interest about the use of online targeting on large platforms.

Our research demonstrates that online targeting systems used by social media platforms (like Facebook and Twitter), video sharing platforms (like YouTube, Snapchat, and TikTok), and search engines (like Google and Bing) raise the greatest concerns in these areas. Our analysis and recommendations focus on the use of online targeting by these types of platforms.

Our recommendations aim to address the underlying drivers of harm and promote ethical innovation in online targeting. We have developed them in the context of various government programmes, including the proposed Online Harms Bill and review of online advertising regulation, and government announcements on electoral integrity and the reform of competition regulation in digital markets.

Our approach

As set out in our interim report,[footnote 5] we have sought to answer three sets of questions:

- Public attitudes: Where is the use of technology out of line with public values, and what is the right balance of responsibility between individuals, companies and the government? The findings of our public engagement are summarised in Chapter 3. The full report is published here.

- Regulation and governance: Are current regulatory mechanisms able to deliver their intended outcomes? How well do they align with public expectations? Is the use of online targeting consistent with principles applied through legislation and regulation offline? The findings of our regulatory review are set out in Chapter 4. The summary of responses to our open call for evidence is published here.

- Solutions: What technical, legal or other mechanisms could help ensure that the use of online targeting is consistent with the law and public values? What combination of individual capabilities, market incentives and regulatory powers would best support this? Our recommendations are in Chapter 5.

Our evidence base is informed by a landscape summary (led by Professor David Beer of York University); an open call for evidence; a UK-wide programme of public engagement; and a regulatory review of eight regulators. We have consulted widely in the UK and internationally with academia, civil society, regulators and the government. We have also held interviews with and received evidence from a range of online platforms.

Chapter 1: What is online targeting?

Summary

- Online targeting comprises a range of practices used to analyse information about people and then customise their online experience. It shapes what people see and do online.

- This report considers two core uses of online targeting:

- Personalised advertising, which enables advertisers to target content to specific groups of people online based on data held about them.

- Recommendation systems, which enable websites to personalise the content their users see, based on the data they hold about them.

- Both approaches involve using advanced data analytics to observe people, make predictions about their behaviour and show information to them on that basis. These processes can be wholly automated through machine learning.

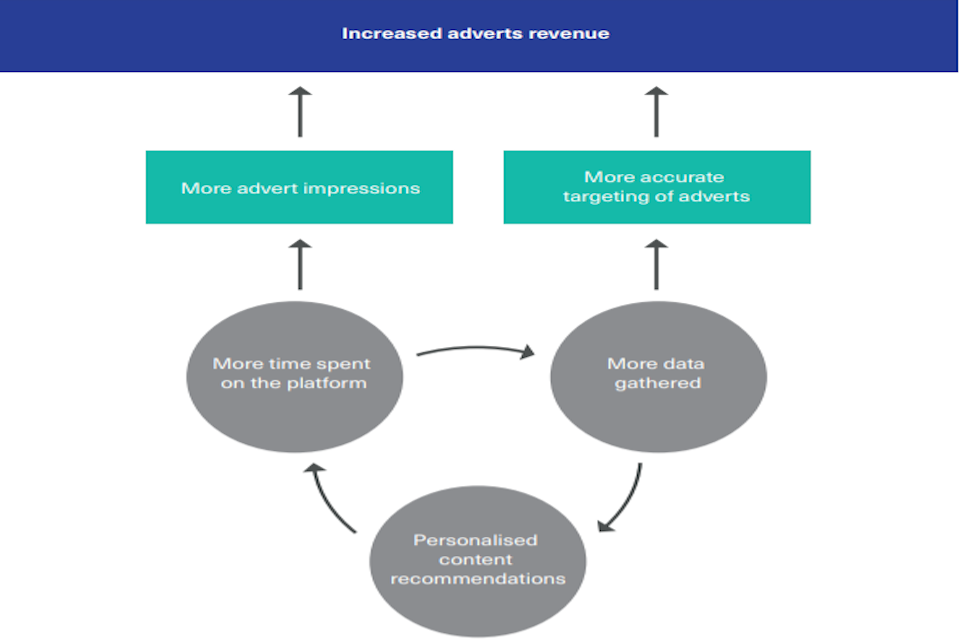

- Online targeting is at the core of the platform business model. Online platforms are among the world’s biggest companies. Recommendation systems encourage users to spend more time on these platforms. This leads to the collection of more data, increases the effectiveness of the recommendations and of the platforms’ personalised advertising products, and makes them more attractive to advertisers.

- An increasing variety of sources of data and applications may enable online targeting to become more sophisticated. Advances in technology may also lead to online targeting becoming less reliant on personal data.

What is online targeting?

In the time it takes you to read this sentence, approximately 100 hours of video will have been uploaded to YouTube and over 72,000 tweets will have been posted to Twitter.[footnote 6]

Individuals only see a tiny proportion of the billions of items of content that are hosted online. And, increasingly, what one person is shown is different to what their neighbour is shown. Automated decisions are constantly being made about what content to show different people. These decisions are made by algorithmic systems that we refer to as “online targeting systems”. They play a critical role in shaping what people see and do online. And this is fundamental to our ability to engage with the online world: without targeting, the mass of information online would be overwhelming, impenetrable and of less value.

Online targeting systems’ effectiveness lies in their ability to predict people’s preferences and behaviours. They collect and analyse an unprecedented amount of personal data, tracking people as they spend time online and monitoring and learning from how they respond to content and how this compares to other people with similar characteristics. This enables them to predict how users will react when shown different items of content. Their predictions are used to decide what content to show people in order to optimise the system’s desired outcome. People’s responses to this content are then collected and fed back into the system in an iterative cycle.

This report considers two core uses of online targeting: personalised advertising and content recommendation systems. Personalised advertising systems aim to increase the effectiveness of online advertising. Content recommendation systems aim to increase user engagement (for example by watching a video, liking a post or sharing a picture). Both work by showing users the content that they are most likely to find engaging. Often this means showing people the content they are most likely to click on.

What has changed?

Companies selling products and services have always used targeting. Advertisers target mailshots based on demographic information about different postcodes. Newspapers publish content that they think will most appeal to their readers. But online targeting is different from traditional forms of targeting in five ways:

- Data: platforms collect an unprecedented breadth and depth of data about people and their online behaviours, and analyse it in increasingly sophisticated ways.

- Accuracy and granularity: content can be targeted accurately to small groups and even individuals.

- Iteration: online targeting systems learn from people’s behaviour to constantly increase their effectiveness in real time.

- Ubiquity: content can be targeted at scale and at relatively low cost.

- Limited transparency: the ability to accurately match people with content inevitably limits the broader scrutiny of that content (including by the media and Parliament) as fewer people see each item of content, and don’t know much about what other users are seeing.

The power and effectiveness of an online targeting system depends on the number of people it affects, the amount of data available, the sophistication of the analysis that is carried out on that data, and the amount and variety of content available for online targeting. This means that major online platforms like Facebook and Google, with billions of users and huge financial resources, are especially well placed to use, and benefit from, online targeting.

Personalised online advertising

Personalised online advertising enables advertisers to target online advertising to specific groups of people using data about them. Selling personalised online advertising is an important part of the business model of many internet companies, including social media, search, and video sharing platforms. In this review, we have largely focused on display advertising rather than search advertising. This is because search advertising has tended to be targeted contextually, based on keywords searched by users, rather than information about the users themselves[footnote 7] (although the CMA and others[footnote 8] have noted that the line between contextual and personalised advertising is being increasingly blurred).[footnote 9]

Personalised online advertising systems use a broad range of data about people: their demographic characteristics, interests, location, devices, personality types and more.[footnote 10] Data is collected, inferred and combined into digital profiles (see Appendix 1), by data-brokers (companies that collect and buy data in order to aggregate the information and sell it on), other actors within the online advertising ecosystem, and the platforms themselves.

Personalised online advertising enables advertisers to specify their target audience and how many people they want to reach, with more precision and often more cheaply than they can offline.

Personalised online advertising makes it easy for advertisers to test different messages with different audiences and monitor how people respond. This is often referred to as “A/B testing”. Analysing the results and feeding them back into the online targeting system enables advertisers to improve the effectiveness of their advertising.

The sophistication of these tools, and the ease of accessing them, represents a step change from older forms of offline and online advertising. Traditionally, targeting has been based on the likely consumers of a type of media (for example a typical newspaper reader), rather than personal information. In traditional advertising, advertisers may test concepts with focus groups before distributing their adverts regionally or nationally, or test the outcomes of running adverts in different media. They reach their target market by distributing their adverts in the media that advertisers’ data show they are more likely to consume. For example, upmarket fashion brands may pay for outdoor advertising in more affluent neighbourhoods, print advertising in high-end fashion magazines, or contextual online advertising based on the site’s content and aggregate audience.

There are two main types of targeted online advertising: “programmatic” advertising outside of platform environments and personalised advertising on platforms.

Programmatic advertising

Programmatic advertising allows advertisers to target the people they want to reach across the internet.[footnote 11]

A commonly used programmatic approach involves “real time bidding”. When someone visits a website, the website publisher auctions advertising spaces to multiple advertisers through an auction system. This includes information about the person visiting the website, likely gathered through tracking technologies embedded in websites such as cookies and fingerprinting. Advertisers may attempt to build a more detailed picture of the person by referring to data held by data brokers and others. Based on this information, they decide how much they think it is worth to advertise to this person, and bid for the advertising space on that basis. The highest bid wins the right to use the advertising space.

This whole process happens instantaneously. It involves many companies, sharing significant amounts of data (including personal data) between them. Academics have estimated that over 50 adtech firms observe at least 91% of an average user’s browsing history by virtue of data sharing through the real time bidding process.[footnote 12] Billions of online ads are placed on websites and apps in this way every day. The ICO outlines in detail how real time bidding works, and its concerns about its compliance with data protection law, in its update report into adtech and real time bidding,[footnote 13] and continues to develop regulatory responses.[footnote 14] The CMA discusses real time bidding in its interim report on online platforms and digital advertising.[footnote 15]

Personalised advertising on platforms

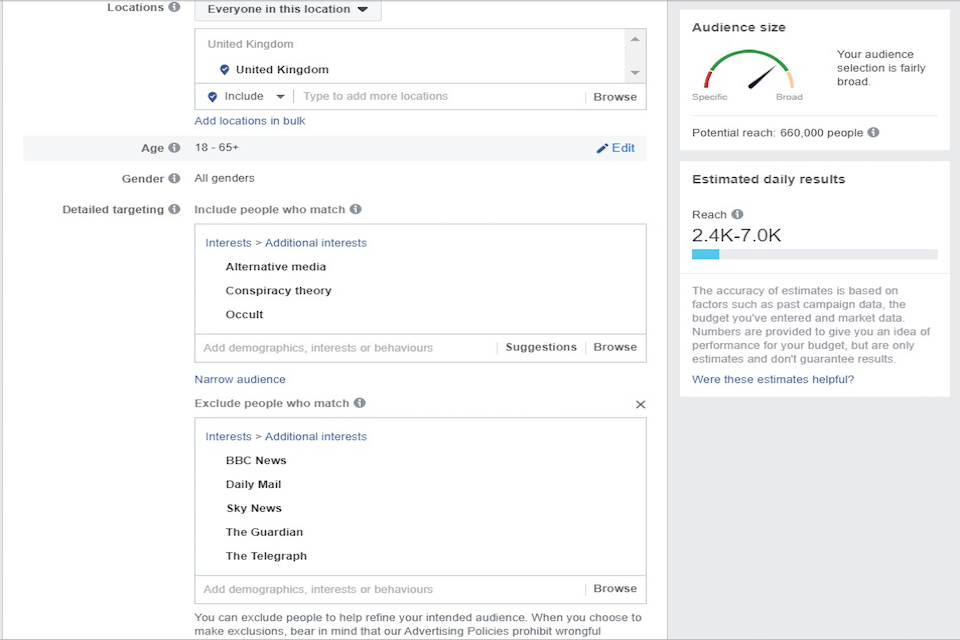

Platforms like Google and Facebook provide tools that advertisers can use to target their user bases. This targeting is performed using data that platforms have collected and inferred about their users based what they do on the platform and elsewhere online, and data provided by advertisers. This may include sensitive data, or enable sensitive characteristics to be inferred.[footnote 16]

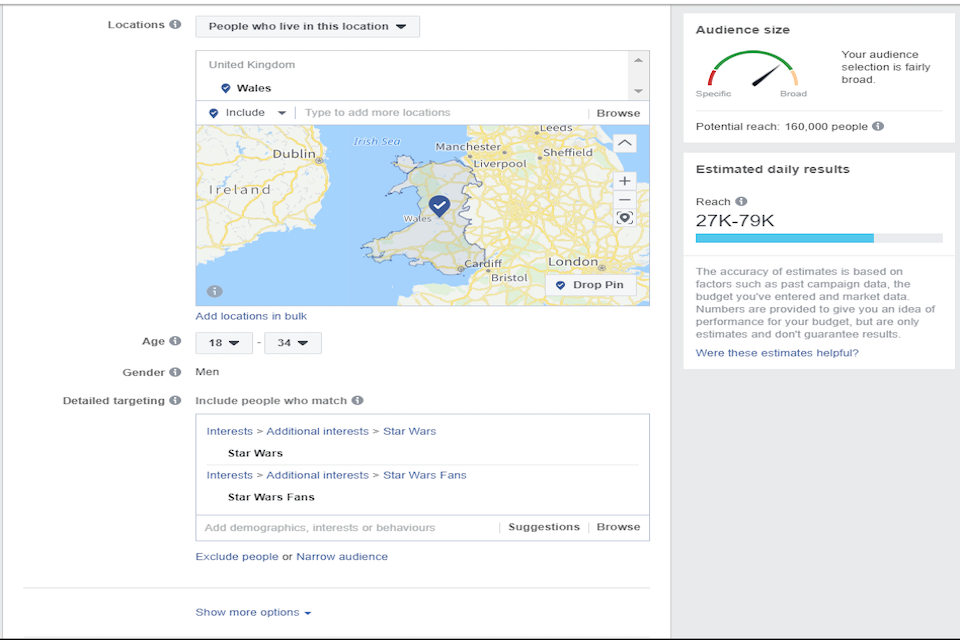

Figure 1: Facebook - Male Star Wars fans aged 18-34 living in Wales

Many platforms also enable advertisers to target “custom audiences”, using the advertisers’ own data (“hashed” so that no identifiable data is transferred). This enables advertisers to target their own customers by matching common features such as an email address or phone number to the platform’s data. Advertisers can also target potential customers by using platforms’ tracking code on their websites to show adverts to them when they visit the platform.[footnote 17]

Platforms also provide tools for advertisers to target “lookalikes” of their existing customers. Lookalikes are the platform users that are identified as those who most closely resemble an advertiser’s existing customers. This is typically based on an overall measure of each user’s similarity to other users, which is constantly iterated on as more data about users is collected. Facebook, for example, offers lookalike advertising to an accuracy of 1% of its user base.[footnote 18] In other words, the advertiser can target the 1% of Facebook’s user base that most closely resembles an uploaded or tracked audience, though this depends on the quality of data held about those customers.

The platforms offer sophisticated analytics tools. Advertisers can easily compare the effectiveness of different adverts with a particular audience, or compare the effectiveness of the same advert with different audiences. This allows advertisers to determine which language and visual features are most effective for persuading an audience to do something and learning which potential audiences are most valuable.

Optimising for different measures of effectiveness will lead to different results. For example, a brand seeking to drive online sales may require the platform to optimise for product sales. This could lead to a small number of the most valuable potential customers viewing a high frequency of adverts. A brand seeking to raise consumer awareness of its product may optimise for reach. This could lead to more people seeing the advert at lower levels of frequency.

Divides are blurring, between offline and online, and between contextual and personalised advertising. Advertising company Global offers geotargeted advertising on digital London buses, meaning that the advert on the side of the bus changes based on GPS data.[footnote 19] Sky’s AdSmart product applies personalisation to television advertising, allowing companies to serve different adverts to different households “based on millions of different data points”.[footnote 20]

Content recommendation systems

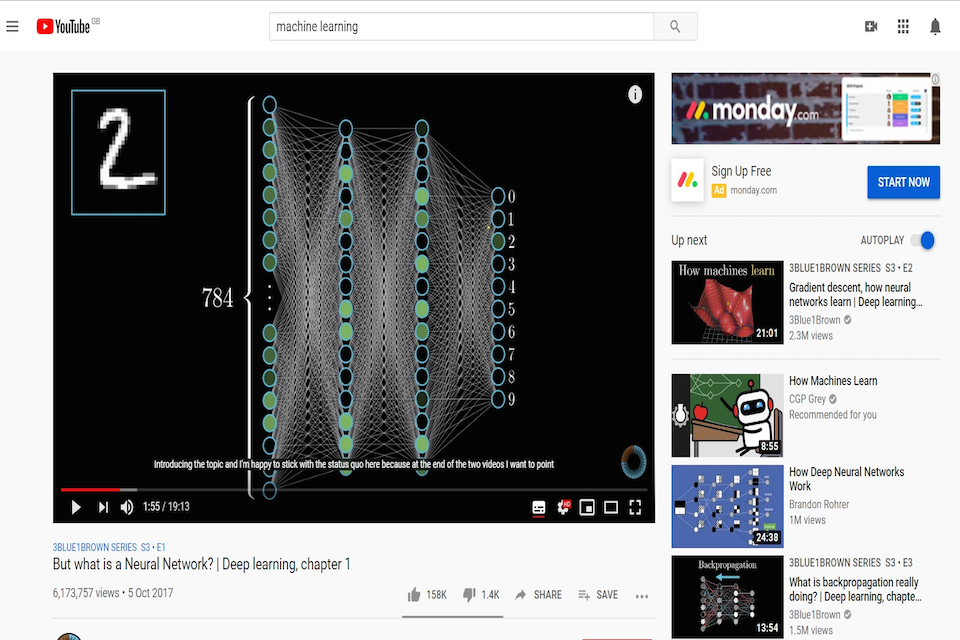

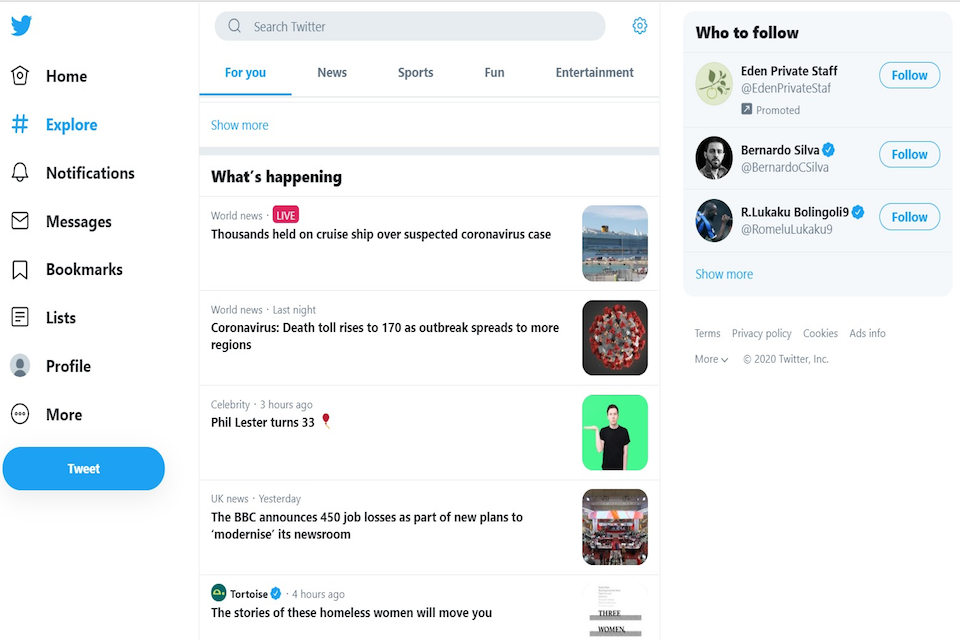

Content recommendation systems enable websites to personalise what each of their users see. Social media feeds, search engine results and recommended products and videos all rank content based on what they know about their users. Platforms use this analysis to determine what content is displayed.

Content recommendation systems generate an individual ranking of the content hosted by the platform (e.g. posts, videos, products) for a specific user. This ranking uses factors such as the type of content, its source, how recently it was uploaded, how others engaged with it, and how the user has historically engaged with similar content. The system will then show content to users in order, so that the first thing a user sees is the item of content that the system has determined they are most likely to respond to. Like personalised advertising, content recommendation systems collect data and analyse it to create digital profiles and assess users’ similarity to one another.

Online platforms can also use content recommendation systems to enforce their content policies. Where content does not meet criteria for removal but may nevertheless breach their policies (for example misinformation), platforms reduce its ranking or stop recommending it altogether, so fewer people see it. For example, Facebook’s recommendation system tries to identify and reduce the prominence of posts with exaggerated or sensational health claims.[footnote 21] In this case, its system identifies commonly used phrases to predict which posts are likely to breach their policies and refers them to human moderators or fact checkers, who can then decide to downrank it. However, because of the cultural context and nuance in language and images used in online posts, automated systems may not be as good as humans at identifying content correctly.[footnote 22] Many major online platforms also employ human moderators to support this process, though many content moderation decisions may be difficult for humans, too.[footnote 23]

Figure 2: On YouTube, recommended “Up Next” videos are displayed next to the video that a user is watching

Figure 3: On Twitter, news and events are recommended to users based on what the platform thinks will interest the user

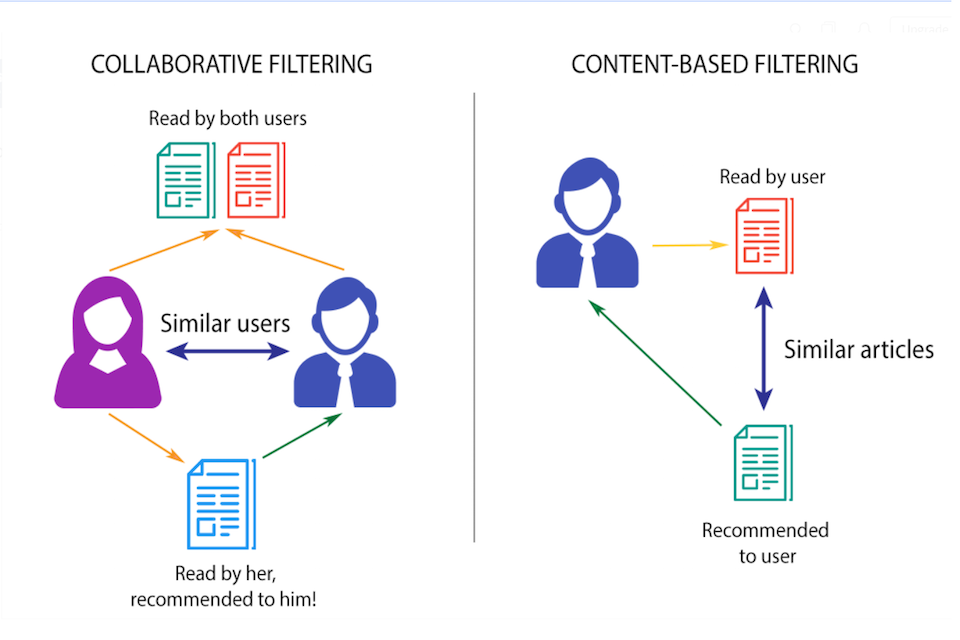

There are two main types of content recommendation systems: content-based filtering and collaborative filtering.[footnote 24] Content-based filtering systems recommend content based on its similarity to content previously consumed by the user (“picture X has a similar title to previously viewed pictures Y and Z”). Collaborative filtering systems recommend content based on what similar users have consumed (“people A, B and C like this; a similar person D might also like this”). Some platforms use hybrid approaches combining features of both methods.[footnote 25]

Figure 4: Collaborative and content-based filtering approaches[footnote 26]

Recommendation systems can also be analysed based on the type of recommended content:[footnote 27]

- Closed: recommended content is generated or curated by the platform itself.

- Open: recommended content is mostly user-generated. User-generated content is automatically added to the recommendation engine to be surfaced to users.

For example, BBC iPlayer is a closed system, which serves a mix of BBC content, including manually curated and personalised content recommendations, which for signed-in users are based on previous viewing history.[footnote 28] YouTube is an open system, and takes many more variables into account when recommending content.[footnote 29] Pinterest is also an open system. It encourages users to proactively indicate their interests, and uses this information to determine what content to promote to them.[footnote 30]

As someone spends more time on the platform, the recommendation system learns how they, and similar users, respond to different content. It then uses this learning to generate more accurate predictions of what content they are likely to respond to, and how, in the future.

As with personalised advertising, recommendation systems can be optimised to serve different business goals. For example, a platform focused on rapid growth may focus on short-term engagement metrics like clicks, whereas a platform focused on maximising long-term use (leading to a greater number of overall clicks) may adopt metrics that could correlate with a higher quality experience, such as the length of time a user spends reading an individual article.[footnote 31]

Recommendation systems are a new way of spreading information. Like editors of print and broadcast media, recommendation systems give prominence to certain types of content. In traditional media, these decisions are based on the editor’s view of what is likely to appeal to their readership or audience. Traditional editorial approaches involve human judgment, a single product, and a lack of information about readers or viewers at an individual level. Recommendation systems, by contrast, involve automated predictions about what will appeal to an individual, based on knowledge about that individual (see Box 1: Machine Learning and Online Targeting).

Box 1: Machine Learning and Online Targeting

Some modern online targeting systems use a machine learning technique called deep learning. This is a powerful pattern recognition system that can uncover relationships between different pieces of content. The systems uncover relationships by assigning numerical values to aspects of the content such as words in a sentence or the colours in an image. These values are then used to produce a model of the relationships between values, and how users interact with pieces of content that have been assigned the same or similar values. Content is disseminated according to mathematical values the system has assigned it. A machine alone cannot appraise that content in context as a human can. As such, if constraints cannot be specified in a form a machine can easily interpret, it may recommend content in a way a human curator would not (see Appendix 3).

The role of online targeting in the business models of major online platforms

Online platforms are digital services that facilitate interactions between users. While they have different business models, they share some core features. They make connections, between buyers and sellers (as in online marketplaces), people and information (as in search engines), or people themselves (as in social media). They generate revenue by enabling advertisers to target their users.

The platform business model has been harnessed most effectively by a small number of American and Chinese companies including Google, Facebook, Amazon, Tencent and Alibaba, which have gained vast, and in many cases, global user bases.

Seven of the world’s largest ten companies,[footnote 32] and the world’s top 10 most visited websites, are online platforms.[footnote 33] 89% of the UK internet audience aged 13+ shops on Amazon, 90% has a Facebook profile, and 73% of UK adults report consuming news on Facebook.[footnote 34] Google and Facebook together generated an estimated 61% of UK online advertising revenue in 2018.[footnote 35]

How online targeting drives the online platform business model

Content recommendation systems and personalised advertising work together to drive the success of the biggest online platforms. Content recommendation systems encourage users to spend more time on the platform and in the process users share more data about themselves. This increases the amount of revenue that can be earned from personalised advertising in three ways. First, users spend more time on the platform, increasing the number of opportunities to serve adverts to users. Second, it is easier to predict individual user behaviour, increasing the amount that platforms can charge advertisers for reaching the right people. Third, users may find personalised adverts more relevant, increasing their tolerance for an increased number of adverts. Every action users take enables the platform to extract more data, driving the value of the platform.

Figure 5: Role of online targeting in platform business models reliant on advertising

In economic terms, platform business models are characterised by network effects, both direct (where a platform is more valuable to individual users the greater the number of other users also active on the platform) and indirect (where the value for users on one side of the platform such as content producers and advertisers increases with the number of users on the other side of the platform). As more users are attracted to both sides of a platform, and more content is hosted, online targeting systems become increasingly important, as they enable users to navigate the platform and advertisers to reach their target audience. They also increase the platform’s ability to collect and monetise data about their users, improving their services and entrenching the network effects by attracting more users to both sides of the platform.

Online markets have also seen the emergence of “ecosystems”, offering different products and services under the same brand and extending the network. Google has built on its initial search engine with email (Gmail), a mobile operating system (Android), geographic services (Google Maps) and video streaming (YouTube). Through these different services, it can collect even more data about users that it can use to improve its online targeting systems and further increase user engagement and revenue.[footnote 36] While some of these products have been developed in house (Android), others (YouTube) have been the result of strategic acquisitions.

Many platforms offer tools that embed tracking technologies in third party websites and apps. These provide analytics services but also enable platforms to collect more data about the users of the apps and websites that install them. Such trackers are now widespread. For example, research shows 88% of Android apps contain a Google tracker, 43% contain a Facebook tracker, and 34% contain a Twitter tracker.[footnote 37]

Platforms are increasingly acquiring or developing physical products that enable data collection in traditionally offline environments. These include products for the home such as smart speakers,[footnote 38] thermostats,[footnote 39] and video doorbells.[footnote 40] Platforms are also investing in wearable technology involving activity trackers[footnote 41] and operating systems for cars.[footnote 42] The rollout of 5G is predicted to create new opportunities for platforms to extend their networks of connected devices[footnote 43] and target users with greater sophistication through more accurate location sharing with apps. This may enable companies to target consumers more accurately with location or time-specific offers.[footnote 44]

Box 2: The influence of Chinese platforms

In China, a parallel ecosystem of platforms has developed. This reflects the inability of Chinese people to access many of the American-owned platforms, as well as different consumer expectations from online services. Companies like Tencent, Alibaba, ByteDance and Baidu have grown to become some of the world’s biggest businesses, largely catering to Chinese consumers. In the 2000s, many Chinese internet companies developed as near-imitations of their international counterparts.[footnote 45] However, in recent years, some of the features of Chinese platforms are being adopted by American platforms and ByteDance-owned TikTok has become successful in the West in its own right.

Tencent-owned WeChat is a social media messaging platform which has been described as China’s Facebook. However WeChat includes many other features within a single app, including payments, search, travel booking, taxi hailing, and the ability to buy services including utilities, healthcare, lottery tickets and visas.[footnote 46] Personalised advertising represents a comparatively smaller share of WeChat’s revenue, with the platform receiving a processing fee for its payments service and users’ data used to help sell other services, such as video gaming.[footnote 47] Facebook has adopted features associated with WeChat, including video gaming within Messenger. In 2019, Mark Zuckerberg announced the future of Facebook would involve a greater focus on encrypted, private groups[footnote 48] and plans for its own payments system.[footnote 49]

ByteDance is the first Chinese platform to develop a significant user base in Europe and the United States. The company’s two main products in China are Douyin, a recommender service for user-generated short videos, and Toutiao, a personalised news aggregator. ByteDance’s international products include TikTok, which follows a very similar use design to Douyin, and news aggregator NewsRepublic. TikTok was launched in 2017 and is reported to have acquired 500 million monthly active users (more than Twitter, LinkedIn or Snapchat).[footnote 50] At the time of writing, it is the most downloaded free app in the Android app store and the fourth most downloaded app in the Apple iPhone app store.[footnote 51] It is particularly popular among children and young adults, and organisations including the British Army and Washington Post are now using the platform to reach younger people.[footnote 52]

While the importance of online targeting systems is clear, it is difficult to quantify their impact with publicly available information. Studies released by major online platforms tell us, for instance, that 35% of purchases on Amazon,[footnote 53] 70% of views on YouTube[footnote 54] and 80% of all user engagement on Pinterest[footnote 55] come from recommendations. In 2016, Netflix valued its recommendation system at US$1 billion per year and showed that “when produced and used correctly, recommendations lead to meaningful increases in overall engagement with the product (e.g. streaming hours) and lower subscription cancellations rates”.[footnote 56] Google has stated that the YouTube recommendation system “represents one of the largest scale and most sophisticated industrial recommendation systems in existence”, with “enormous user-facing impact”.[footnote 57]

Conclusion

Online targeting systems are changing rapidly in response to new technologies, new regulations, and new ways in which people interact with online content.

Many respondents to our call for evidence highlighted that the direction of travel is towards more sophisticated, and intrusive, predictions, and an increased role for targeting technologies in different areas.[footnote 58] They highlighted the availability of new data sources, the adoption of new approaches such as facial recognition and improved sentiment analysis, and the potential to combine online and offline data. Others suggested that emerging technologies and the widespread uptake of encryption will lead to improvements in privacy. This could allow for targeting to become more accurate without personal data being shared, though would not necessarily mean reductions in the power of targeting or the tracking of user behaviour.[footnote 59]

In the next chapter, we assess online targeting in the context of the OECD human-centred principles on Artificial Intelligence. We explain how limited transparency and accountability over online targeting is a hazard. We discuss the benefits and harms online targeting can lead to, in particular in relation to autonomy and vulnerability, democracy and society, and discrimination.

Chapter 2: Why does online targeting matter?

Summary

- Online targeting is powerful: it enables people’s behaviour to be monitored, predicted and influenced at scale. It also contributes to and benefits from platforms’ market power.

- Online targeting systems used by major online platforms help people to make sense of the online world. Further innovation in ethical recommendation systems can benefit people and society.

- However, the major online platforms have harnessed the power of online targeting with low levels of accountability and transparency. This falls short of the UK-endorsed OECD principles for the ethical use of artificial intelligence and calls into question the legitimacy of the platforms’ power.

- In these circumstances, the operation of powerful online targeting systems is a hazard. There is some evidence of harms caused by online targeting systems in relation to autonomy and vulnerability, democracy and society, and discrimination. However, the ability to understand the impact of online targeting systems is limited because much of the evidence base lies with the major platforms themselves.

- The way in which online content is targeted is a critical factor in determining how harmful it is likely to be. This is highly relevant for the UK government’s proposed Online Harms Bill.

Online targeting as a form of power

A new way of consuming information

Online platforms are used by people all over the world to connect with others, and create and access a wide range of content. The content each user is shown on the platform is personalised to them by online targeting systems. The content they see may be provided alongside private messaging services, blurring the lines between private and public spaces.

In the analogue world, ideas travel through public debate and personal networks (families, friends and colleagues), and through institutions (the media, the state and religious institutions). Unlike online platforms, these institutions select the information they share on the basis of its expected level of public interest and its fit with their agenda.

Changing power structures

The role online platforms play in society, and their use of online targeting systems, translates to significant social and political power. This power can be exerted by the platforms themselves. It can also be harnessed by others who use platforms, from bloggers and activists, to charities and political parties, to terrorist groups and hostile state actors.

The four key elements to platform social and political power are:

- Observation: the platforms can observe people’s behaviour in environments where they have an expectation of privacy, such as the home. Knowledge about individuals makes it easier to influence their actions. When people know they are being observed they may behave differently.[footnote 60]

- Influencing perception: the platforms have become a major source of news and information.[footnote 61] The decisions made by online targeting systems influence the flow of information in society and this affects what people perceive as normal, important and true.[footnote 62] This impact is compounded by the fact that people do not know that this process is taking place: it does not involve a conscious choice like turning on the TV or picking up a newspaper.

- Prediction and influence: organisations using online targeting systems can learn from how people react to content and use this knowledge to make increasingly accurate predictions which can be used to influence people’s actions and even beliefs, as individuals, but also across populations.

- Control of expression: online platforms, through their content policies and dissemination systems, are able to play a major role in determining how people express themselves and how far those views travel.

Online targeting and the power of the major online platforms

A concentrated market

Online targeting has been used most successfully by a number of online platforms operating in search, social media and video sharing. The Digital Competition Expert Panel report (the Furman report) describes a tendency for a small number of companies to dominate digital markets,[footnote 63] while Ofcom analysis shows that the characteristics of some online services can lead to a range of market failures, including market power.[footnote 64]

Market effects

The UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) interim report on its market study into online platforms and digital advertising found that Google and Facebook are “the largest online platforms by far, with over a third of UK internet users’ time online spent on their sites”. It concludes that their profitability has been “well above any reasonable estimate of what we would expect in a competitive market”, and that they “appear to have the incentive and ability to leverage their market power… into other related services”. Their control over user data, and ability to use it in their online targeting systems, is an important factor in this.[footnote 65]

While the CMA did not report any direct evidence of abuse of their market power, it comments that if competition in search and social media is not working well, this could lead to reduced innovation and choice in the future, and to consumers giving up more data than they feel comfortable with. It states that weak competition in digital advertising can increase the prices of goods and services across the economy and undermine the ability of newspapers and others to produce valuable content.

Further harms from high online platform concentration

Market failures, including market power, could in some cases lead to a range of consumer and societal harms. Online targeting could play a role in this. Ofcom sets out that some online services are incentivised to maximise the data and attention they capture from consumers, using processes which are made more effective by online targeting. This can help to increase the value of the platform to advertisers, but could also contribute to the spread of harmful content. Further, Ofcom highlights that if this data is used to influence consumer decision making through online targeting, this may limit users’ exposure to a variety of views.[footnote 66]

Legitimacy

The major platforms’ market position means they have been best able to exercise the power of online targeting. This, in turn, gives them significant social and political power. In this context, it is not necessarily clear who (online platforms, governments or users) has the most legitimate authority to set rules about how content is promoted.

It could be considered legitimate for platforms to set these rules, because their users individually offer consent by using the service.[footnote 67] On this basis, newspapers are largely self-regulating. Democratic governments could also claim legitimacy to set these rules as their power is derived from the consent of the governed.[footnote 68] On this basis, broadcasting is subject to statutory regulation. Another argument is that platform users have the greatest legitimacy to set the rules. This could be for democratic reasons (platform users should have the right to shape the rules they are required to follow) or because users are part of a community that generally offers benefits (so they should be required to follow group norms, but be able to influence these in some way, including through informal mechanisms).[footnote 69] On this basis, political parties elect their leaders.

We do not believe that platforms have full legitimacy, because of the lack of consumer choice between platforms and because platforms’ decisions have impacts on people who are not their users. Platforms may not always wish to be in positions of political power - some have expressed concern about having to take choices that would historically have been left to democratically elected governments.[footnote 70] We therefore think that democratic governments and citizens should play a bigger role in deciding how online targeting is governed.

Applying an ethical framework

We aim to help create the conditions where ethical innovation using data-driven technology can thrive. There are a number of ethical frameworks that we can draw on to guide our thinking.[footnote 71] In particular, we have welcomed the commitment of 42 countries, including the UK, to the OECD human-centred principles on AI.[footnote 72] These are framed specifically with reference to Artificial Intelligence and are therefore directly relevant to the content recommendation systems driven by machine learning. They also provide a relevant framework for evaluating any complex algorithmic system and are therefore relevant to online targeting in general.

As discussed in Chapter 2, online targeting helps people to make sense of the online world. Without online targeting, it would be harder for people to navigate virtually unlimited content to find the news, information and people that have meaning and value to them. Whether people are using an app, connecting with fellow enthusiasts to talk about a hobby, looking for a job, or catching up with the news, online targeting shapes what they see.

Online targeting is integral to many online business models. It lets companies, including small companies, reach people who may be interested in their products and services more cheaply and easily. And it has great potential to be used in the public sector, to help people find training, avoid risky behaviour and make healthy life choices.

However, we believe that the use of online targeting systems by major online platforms is currently inconsistent with the OECD principles.

A high-level assessment of online targeting systems used by major online platforms against the OECD human-centred principles on AI:

AI should benefit people and the planet by driving inclusive growth, sustainable development and well-being.

Assessment: While online targeting systems offer economic benefits to people and businesses, they have also contributed to the significant market power of a small number of major online platforms. The impact of online targeting on wellbeing is highly contested. For example, the Royal College of Psychiatrists argues that there is growing evidence of an association between social media use and poor mental health, but that the lack of research on the connection between mental health and technology makes it difficult to identify causality.[footnote 73] Moreover, the information needed to establish the balance of benefits and harms is only accessible to the major online platforms.

More research should be done on the impact of online targeting on sustainable development, though some studies warn that online advertising uses high levels of energy.[footnote 74]

AI systems should be designed in a way that respects the rule of law, human rights, democratic values and diversity, and they should include appropriate safeguards

Assessment: Online targeting systems may undermine the rule of law by disseminating illegal content and facilitating unlawful discrimination. They may impact negatively on human rights, such as privacy, data protection and freedom of expression. And the targeting of political content online may undermine democratic values by enabling political campaigning to take place in a way that is not visible to opponents and as a result cannot be properly contested in public discourse.

There should be transparency and responsible disclosure around AI systems to ensure that people understand AI-based outcomes and can challenge them.

Assessment: There is very limited transparency over online targeting systems, to users and to society more widely. Users are not provided with sufficient understanding or control of online targeting.

AI systems must function in a robust, secure and safe way throughout their life cycles and potential risks should be continually assessed and managed.

Assessment: Risks associated with online targeting systems are assessed and managed inconsistently. Many online platforms have introduced processes designed to mitigate some risks, such as the spread of misinformation through content recommendation systems. However, these tend to be reactive instead of proactive and are not subject to any scrutiny or independent oversight. In this light, it is difficult to assess if they are sufficient.

Organisations and individuals developing, deploying or operating AI systems should be held accountable for their proper functioning in line with the above principles.

Assessment: Organisations that choose to use online targeting systems (and the people that make decisions to do so) need to be accountable for their effects. There is currently no effective mechanism in the UK for online platforms that use online targeting systems to be held to account.

The OECD principles contain three concepts that we believe are particularly relevant to this review: transparency, safety and accountability.

Generally, people do not understand how online targeting can affect them and what they can do about it. Individual users often do not know what data platforms hold about them, how they collect it and how it is used in their online targeting systems. They may not be aware that they are seeing targeted content. Even if they are, it may not be clear where the content has come from, why it has been targeted to them and what content they are missing out on. Users are therefore less likely to be able to evaluate the content critically, and to know when and how they may have been harmed by an online targeting system. When they are aware, there may not be a satisfactory way for people to seek redress from platforms.

On top of this, many online platforms also offer limited transparency to society more widely (regulators, the media, civil society organisations, academia, government, Parliament and so on). In recent years, some online platforms have started to make some information available publicly about their operations in the form of transparency reports, but these are limited, not independently verified and not comparable across platforms.

The UK Government’s Online Harms White Paper (see Box 5 below) sets out a range of evidence of unsafe targeting practices.[footnote 75] It notes that some companies have taken steps to improve safety on their platforms, but that overall progress has been too slow and inconsistent. The Carnegie UK Trust has argued that many online platforms have failed to systematically monitor and mitigate the risks their systems pose to users.[footnote 76]

The operators of these systems are not currently held to account in any meaningful way. There are few regulatory incentives for them to empower their users and align more closely with their interests, and the interests of society more widely. Given their global nature, the fast pace of change in technology and its uses, the complexity of platform business models, the scale of content they host and the variety of services they offer, regulation has not yet adapted to enable online platforms to be held to account where it may be necessary.

We set out further evidence supporting these assessments in the remainder of this chapter, where we consider the harms and benefits of online targeting. In Chapters 3 and 4, we draw on our research into public attitudes towards online targeting and our review of the strengths and weaknesses of the UK regulatory environment to set out further evidence.

Benefits and harms of online targeting

Online targeting plays an essential role in people’s lives. However, currently it is a significant hazard. As set out in the introduction to this report, we have focused our work in this review on the areas we have found to be of greatest concern to the public, and where we assess there are significant regulatory gaps. We have looked in depth at the role of online targeting plays in three areas: autonomy and vulnerability, democracy and society, and discrimination.

Limited evidence base

There is limited understanding of the impact of online targeting on individuals and society. Beyond anecdote, little empirical evidence is available to assess the risks posed by online targeting and the extent of the harms it causes or exacerbates. This view has been expressed widely: many respondents to our call for evidence cautioned that there is limited reliable evidence in the public domain about how online targeting works and the impacts it has on people and society.

However, absence of evidence of harm is not evidence of absence of harm. Where there is anecdotal evidence of people experiencing harm caused or exacerbated by online targeting systems, it is possible that other people have also experienced similar harms. Much of the information needed to understand the extent of harm is only accessible to the major online platforms. Respondents to our call for evidence saw this as a serious problem for policymakers and regulators.

The following section outlines some of the available evidence about the benefits of online targeting, and the harms it may cause or exacerbate. In some cases, platforms have told us that their practices have changed since the incidents cited.[footnote 77]

The benefits and harms captured below do not apply uniformly across all online targeting systems. Different applications of online targeting carry different risks, depending on the content they target and what they are optimised to achieve. For example, in broad terms, content recommendation systems used by social media and video-sharing platforms aim to highlight relevant and engaging content to keep users on the service for longer, whereas those used by search engines aim to find relevant and engaging content to direct users off the service as quickly as possible. In this case, risks that people get stuck in “rabbit holes” are higher on social media and video-sharing platforms than on search engines.

Autonomy and vulnerability

Benefit: Navigation and discovery

Online targeting helps people to navigate the vast amount of information available online by showing them content it has predicted they will engage with. It can also broaden people’s horizons through content “discovery”, by suggesting content that they wouldn’t have sought out but which might be beneficial to them. For example, a study has found that 79% of all consumers, and 90% of those under 30, agree that streaming services that use online targeting systems play a huge role in their discovery of new video content.[footnote 78]

Benefit: Influencing behaviours and beliefs

There are also great opportunities for applications of online targeting to influence people’s behaviour positively. Used responsibly, online targeting can help people make informed choices and support important public information campaigns. For example the Department for Transport achieved an 11% increase in young men who thought it was unacceptable to let a friend drive after drinking, following an online public awareness campaign targeting them.[footnote 79]

There is a growing number of tools and apps that provide personalised information and advice to people, for example to help them maintain a healthy diet and progress in their education. British company Sparx Maths provides an online learning tool that assesses students’ maths ability based on their homework performance. It then generates class and homework tasks tailored to their ability.[footnote 80]

Benefit: Protective online targeting

Online targeting can also be used to predict where people may be susceptible or vulnerable to particular harms and aim to prevent them seeing potentially harmful content. For example, online targeting systems could be used to avoid showing children advertising for age-restricted products and unhealthy food choices. The Advertising Standards Authority (ASA)’s Code of Non-Broadcast Advertising and Direct & Promotional Marketing (CAP code) says that, when advertised on social media, the ASA expects advertisers “to make full use of any tools available to them to ensure that ads are targeted at age-appropriate users”.[footnote 81]

The Samaritans is working with industry and government to deepen the understanding of how people engage with online content relating to self-harm and suicide.[footnote 82] Some of the major online platforms have attempted to address the potential impact of content relating to self-harm and suicide. Instagram, for example, can (and does) remove, reduce the visibility of, or add sensitivity screens to this type of content, but recognises that sharing this type of content can also help vulnerable people connect with support and resources that can save lives.[footnote 83]

Benefit: Targeted support to vulnerable people

With appropriate safeguards and controls, online targeting could be used to support vulnerable people. Public Health England uses data to target its campaigns to people who show interest in specific topics (such as mental health issues), or people in areas where the prevalence of specific conditions is high. This enables them to provide more tailored messaging and to be more efficient with their resources. The NHS Mid-Essex Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) ran an advertising campaign on Facebook to raise awareness of local mental health services, targeting 18-45 year-old men, who are most at risk of suicide. After a four-week trial, traffic to the CCG’s website increased by almost 74% (of which 341 visits came directly from Facebook, compared to just 24 visits the previous month). Overall, referrals to the service increased by 36% over the trial period, with a marked increase in referrals from men.[footnote 84]

Harm: Exploiting first-order preferences

Online targeting systems are informed by a deep understanding of people and how they behave online. This has led to widespread concern that online targeting systems can exploit people’s “first order preferences” (their impulsive, rather than reflective, responses).[footnote 85] The Mozilla Foundation’s list of “YouTube Regrets” documents real-life stories of YouTube “rabbit holes”.[footnote 86] Experiments have also shown that when adverts were targeted at people based on psychological traits (such as extraversion and openness) inferred about them from their Facebook data, they were 40% more likely to click on the ads, and 50% more likely to make purchases.[footnote 87]

Harm: Manipulating behaviours and beliefs

Online targeting can reinforce people’s existing preferences and shape new ones.[footnote 88] In doing so, it can also have a wider impact on users’ behaviours and beliefs. For instance, by randomly selecting users and controlling the content they were shown (giving some users slightly more upbeat posts and others more downbeat ones), Facebook influenced the sentiment of these users’ posts, which were correspondingly slightly more upbeat or downbeat depending on the content they had been shown. Equally, the ranking of Google search results can shift the voting preferences of undecided voters by 20% or more, without people being aware.[footnote 89]

Harm: Exploiting people’s vulnerabilities

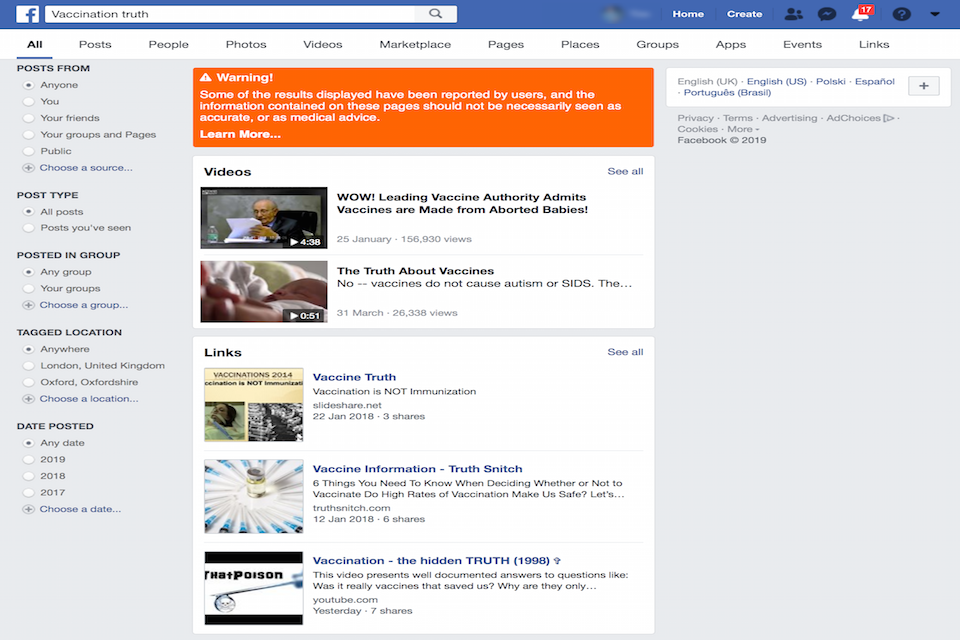

The risk that online targeting poses to autonomy is more significant for people who may be vulnerable.[footnote 90] Many of the “YouTube Regrets” stories referred to above document the experience of children and older people. The ASA has found gambling adverts served to children online, in direct contravention of the CAP code (online gambling adverts are powerful: the Gambling Commission found that 45% of online gamblers were prompted to spend money on gambling activity due to the adverts they saw).[footnote 91] Anti-vaccine groups are known to have used Facebook to target new mothers with misinformation on vaccine safety (Facebook used to allow advertisers to target users it classified as being interested in “vaccine controversies”). The advert and Facebook page in question were later investigated by the ASA and found to be in breach of the CAP code due to misleading claims and causing distress.[footnote 92]

Harm: “Internet addiction”

Some online products incorporate “persuasive design” features to encourage continuous use.[footnote 93] Research has found that online targeting could exacerbate addictive behaviours.[footnote 94] The number of people suffering from clinical addiction in this way has not been reliably quantified, but there are well-documented extreme cases of vulnerable individuals for whom addiction has got in the way of social lives, sleep, physical activity and other parts of a healthy, balanced lifestyle.[footnote 95] While there is limited evidence to demonstrate a causal negative effect on mental health from persuasive design and increased screen time, the UK’s Chief Medical Officers have recommended platforms follow precautionary approaches.[footnote 96]

Amplifying “harmful” content

Content recommendation systems may serve increasingly extreme content to someone because they have viewed similar material.[footnote 97] The proliferation of online content promoting self-harm, including eating disorders, is reasonably well documented.[footnote 98] Ian Russell, the father of Molly Russell, who died by suicide in 2017 aged 14, believes that the material she viewed online contributed to her death and has said that social media “helped kill his daughter”.[footnote 99] The coroner investigating Molly’s death has written to social media companies demanding they hand over information from her accounts, to help find out whether the “accumulated effect” of self-harm and suicide content she had seen “overwhelmed” her.[footnote 100]

Democracy and society

Benefit: Increasing voter participation

Online targeting can help people stay informed about the things that matter to them, from news about their local area, to changes to national education systems, to humanitarian crises in other parts of the world. It can lower barriers to political debate, activity and organisation, enabling people to communicate with others with similar perspectives and helping them to connect online. It may also have the capacity to improve voter turnout.[footnote 101]

Benefit: Giving people “reach”

Some online platforms have increased the ability of people across the world to express themselves and form communities of interest. Online targeting systems have a significant impact on how widely users’ posts are distributed among other platform users, and therefore can be seen to amplify people’s posts. These online platforms are increasingly used in communicating information and organising for social action.[footnote 102] This effect is widely considered to have played a role in democratic movements such as the Arab Spring.[footnote 103]

Benefit: Improving democratic accountability

Online targeting has the capacity to improve democratic accountability, enabling people to be informed of policy decisions that affect them. By targeting messaging to people most likely to be affected by decisions, it may be possible to facilitate more meaningful communication between the government and citizens, or political parties and voters.

Harm: Undermining the news industry and public service broadcasting

Online platforms are widely considered to have had a negative impact on the sustainability of the traditional news media industry.[footnote 104] Online targeting is a factor in this: through their targeting systems, platforms have a significant influence over traffic to news publishers’ websites, and therefore the level of advertising revenue they can generate.[footnote 105] Online targeting may also have an impact on public service broadcasting (PSB), as online platforms, unlike broadcasters, are not required to ensure that public service content is easy to find. Ofcom has recommended legislation to extend prominence rules to television delivered online, and has proposed that PSB content should be given protected prominence within TV platforms’ recommendations and search results.[footnote 106]

In addition, online targeting may make it harder for the news media to play their traditional role of holding politicians to account. It is likely that the widespread personalisation of online experiences reduces the news media’s ability to identify and scrutinise targeted political messaging.

Online targeting can also stop important news from spreading. For example, in 2014 protests took place in Ferguson, Missouri, in response to a fatal shooting of an African American man by a police officer. This news was extensively debated on Twitter on its then chronological (i.e. non-targeted) feed. However researchers found the topic was “suppressed” on Facebook’s algorithmically curated News Feed, because it did not meet the criteria for “relevance”.[footnote 107]

Harm: Polarisation and fragmentation

Online targeting may also lead to social fragmentation and polarisation through “filter bubbles” (which narrow the range of content recommended to users) and “echo chambers”(which recommend content that reinforces users’ interests). Online targeting may also influence the type of online content that people create, as content producers are incentivised to study what types of content is amplified through the online targeting system, and create similar content themselves, increasing people’s exposure to their content and maximising their advertising revenues.

Figure 6: Targeting people with an interest in conspiracies and who do not follow mainstream media

Together with a reduction in scrutiny, this risks an increase in fragmentation and polarisation, as political parties and campaigners are incentivised by the design of online targeting systems to adopt more provocative language or positions that align with their existing supporters’ views on particular issues, rather than seek to persuade people to change their minds.[footnote 108] This is problematic, given democracies rely on people being willing to be persuaded.

Online targeting systems that seek to optimise user engagement have been shown to prioritise controversial, shocking, or extreme content that produces emotional responses.[footnote 109] They have repeatedly been found to play a major role in spreading disinformation and conspiracy theories.[footnote 110] The MIT Media Lab found that false news stories are 70% more likely to be retweeted than true stories, and that true stories take about six times as long to reach 1,500 people as false stories.[footnote 111] In 2019, Caleb Cain spoke out about his experience of radicalisation which he believes to have been brought about when he “dived deeper” into content recommended to him by YouTube.[footnote 112]