Health visiting and school nursing service delivery model

Updated 19 May 2021

Applies to England

This guidance is being reviewed and will be updated in due course. In the meantime, the current guidance should be followed.

This guide sets out details of a modernised health visiting and school nursing service delivery model that is ‘Universal in reach – Personalised in response’.

It supersedes ‘4-5-6’ models for health visiting and school nursing, which are now over 5 years old. Universal, Universal Plus and Universal Partnership Plus have also been superseded and instead reference is made to universal, targeted and specialist services. This revised model has been developed with a range of stakeholders to reflect changes to how services are commissioned and provided locally, and aims to provide a greater emphasis on the assessment of children, young people and family’s needs and the skills mix to respond.

As previously, High Impact Areas and commissioning guides, that accompany and should be used in conjunction with this service model, have also been refreshed to reflect the updated model and include current context and references to related plans and programmes. This includes the NHS Long Term Plan, the Maternity Transformation Programme, Transforming Children and Young People’s Mental Health and Childhood Obesity: a plan for action, chapter 2. No child left behind (Public Health England (PHE) 2020) and Childhood Vulnerability in England (Children’s Commissioner 2019) also provide further context and resources to support children and young people.

The package is intended to support decision-making on the commissioning and provision of public health support for children aged 0 to 19. It will therefore be of interest to local authorities as well as commissioners, health visiting and school nursing provider services, partners including the NHS, voluntary sector, and children, young people and families. It should be read alongside the Healthy Child Programme 0 to 19, health visitor and school nurse commissioning, the public health nursing workforce: guidance for employers and All Our Health, to ensure the Healthy Child Programme is delivered by an effective workforce and is focused on improving outcomes and reduce inequalities, sustaining high quality outcomes for children, young people, families, carers and local communities.

Public health nurses leading the healthy child programme

The Healthy Child Programme offers every family an evidence-base programme of interventions, including screening tests, immunisations, developmental reviews, and information and guidance to support parenting and healthy choices. It also outlines all services that children and families need to receive if they are to achieve their optimum health and wellbeing.

The Healthy Child Programme remains universal in reach continuing to set out a range of public health interventions to build healthy communities for families and children, reducing inequalities and vulnerabilities. It continues to include a schedule of interventions, which range from universal services for all through to intensive support. The updated model emphasises the health visiting and school nursing role as leaders of the Healthy Child Programme, whilst acknowledging the important contribution of a range of delivery partners.

Health visitors and school nurses are specialist public health nurses (SCPHN), with health visitors leading the 0 to 5 element of the Healthy Child Programme and school nurses leading the 5 to 19 element.

Health visitors support families from the antenatal period up to school entry. The service is delivered in a range of settings including families’ own homes, local community or primary care settings. School nurses offer year-round support for children and young people both in and out of school settings.

Whilst both services should be led by health visitors and school nurses as SCPHN, there will also be a skill mix within the team, including community staff nurses and nursery nurses. The determination of skill-mix required should be led by identified local health needs and underpinned by a robust workforce plan.

Health visitors and school nurses utilise their clinical judgement and public health expertise to identify health needs early, determining potential risk, and providing early intervention to prevent issues escalating. Utilising the specialist public health nurse skills provides return on investment, including cost effectiveness and maximising the benefits for parents, children and young people.

Health visitors and school nurses provide continuity of care and undertake a ‘navigating role’ to support families through the health and care system. Utilising the right skill set, at the right time, also supports effective signposting to other support and information.

Health visiting and school nursing delivery model

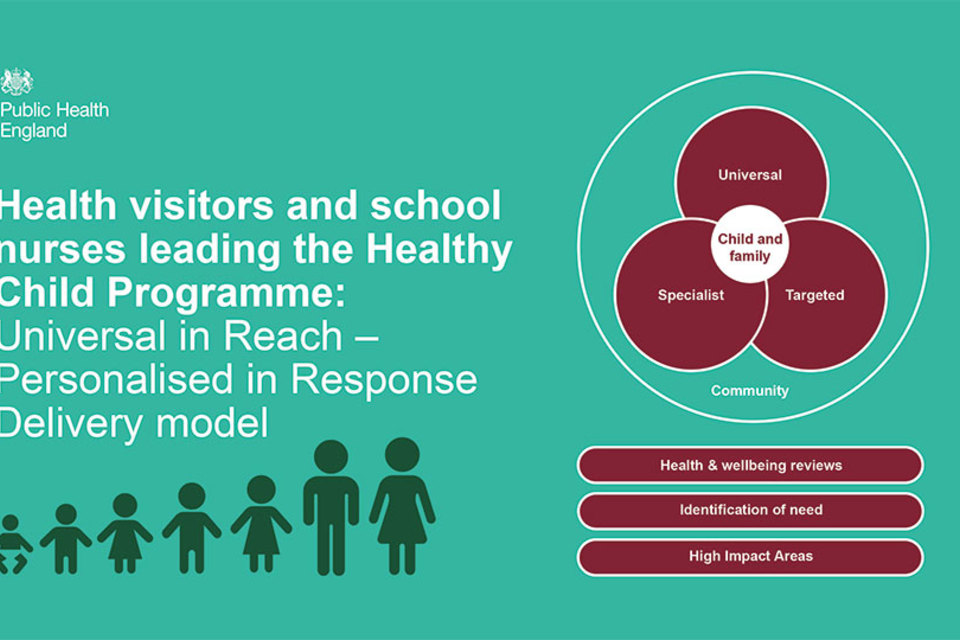

Figure 1 describes the core elements of the ‘Universal in Reach – Personalised in Response’ model, which is based on 4 levels of service depending on individual and family needs: community, universal, targeted and specialist levels of support.

The availability and utilisation of community-based assets is central to the universal offer, while health visitors and school nurses are well placed to identify needs, provide evidence-based public health interventions and signpost to community-centred and asset based approaches (PHE 2018).

Evidence-based interventions provided by health visitors and school nurses should be tailored to meet individual and family needs. There is a connectivity and fluidity between the level of support as these needs may change over time and circumstances. The support required by most families and children or young people will predominantly be met through the universal offer.

Health visitors and school nurses will use a needs assessment to determine targeted interventions which can be met within the services or the need for more specialist interventions that require referrals or clear signposting. Whilst receiving specialist support health visitors and school nurses will still provide the universal offer and work in partnership with other agencies.

Safeguarding children is embedded through the model because health visitors and school nurses have a vital role in keeping children safe and supporting local safeguarding arrangements. It is essential to define local roles and responsibilities including health visitors and school nurses, as identified within commissioning guidance, which includes an example memorandum to support health visiting and school nursing safeguarding. Working Together to Safeguard Children also provides statutory guidance on inter-agency working to safeguard and promote the welfare of children.

Figure 1. Core elements of a universal reach, personalised response model

Figure 2 describes the high level approach taken by health visitors and school nurses to identify and respond appropriately to family needs.

Several core elements are also common to the model. Health visitors and school nurses have a significant role as leaders of the Healthy Child Programme, which should form part of multi-professional care pathways and integration of services to support healthy pregnancy, children aged 0 to 19 years.

Universal services remain essential for keeping children safe and for primary prevention. Early intervention, evidence-based programmes should be used to meet needs in a timely way.

Partnership, integration, communication and multi-agency work remain key to improving outcomes. All areas should be focussing on improving health outcomes and reducing inequalities at individual, family and community levels. Outcome measures should align between health and education or other early years and school age providers to enable shared outcomes across the health and social care system. This involves a broad range of stakeholders in for example, early years, education, voluntary organisations, social services, peer supporters, GPs and primary care teams, oral health and secondary care providers etc. all who have an important contribution to make towards improving child and family health and wellbeing outcomes.

Safeguarding responsibilities apply through all elements from identification of risk and need, to early help and targeted work, and formal child protection.

Health needs will be identified in partnership with parents, children and young people using an approach that builds on their strengths as well as identifying any difficulties. Clinical judgement will be used alongside formal screening and assessment tools. Engagement with the whole family is an important component of the Healthy Child Programme. Public health, health promotion and prevention issues should be integral to make every contact count and promoting healthy conversations.

Outcomes are measured and reported in line with national outcome frameworks and commissioning reporting requirements, with other additional reporting requirements and measures for local determination.

Figure 2. A high level overview of health visitor and school nurse contributions

Health and wellbeing reviews

Key contact points or universal health and wellbeing reviews help identify needs and support or signposting if required.

There are 5 mandated reviews for early years, which are offered to all families. These should be face to face, delivered by a health visitor, or under their supervision. Health visitors should use their clinical judgement to identify whether virtual, other digital or blended approaches can be used to support the needs of a child or family.

Mandated reviews are not the full extent of the health visiting service offer where families may require additional contact and support, for example by a nursery nurse providing parenting support. Additional contacts are suggested for consideration where health visitors, or a member of their team, could respond to a family’s identified needs. For example, at 3 months with support for the continuation of breastfeeding or advice on safer sleep; at 6 months with support for nutrition and accident prevention or managing minor illness advice.

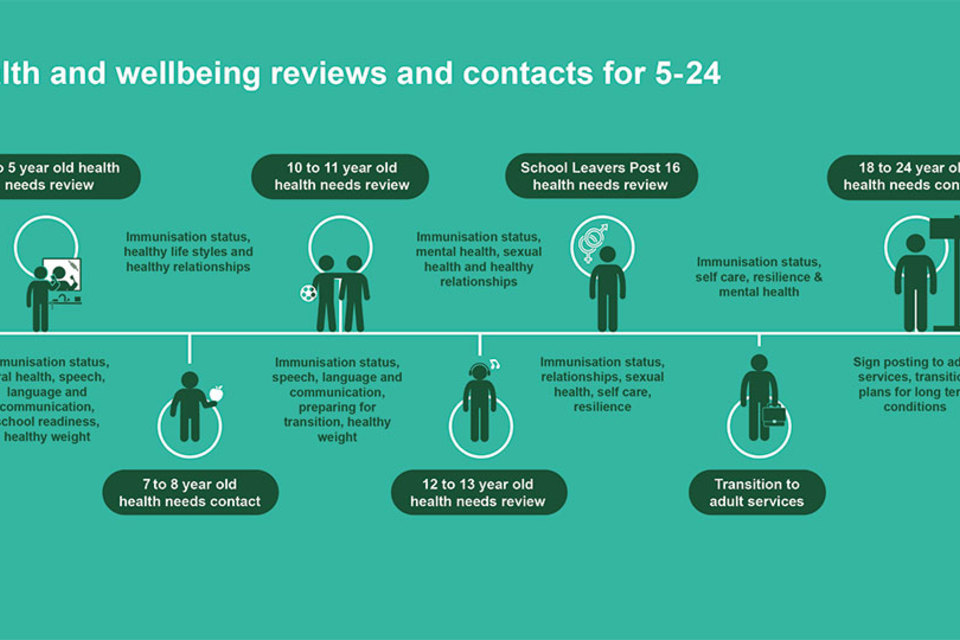

There are no mandated reviews for school-aged children. However, there are opportunities to develop a framework of reviews based on evidence, intelligence, professional judgement and service user voice which would provide contacts to review health and wellbeing needs, support behaviour change and influence outcomes particularly mental health in schools, relationships and sex education and health education.

For school-aged children and young people, suggested contacts are at key development stages or transition points. This includes helping children aged between 7 to 8 years to become more resilient and improve their emotional wellbeing. Delivering evidence-based interventions including human papillomavirus (HPV) and other immunisation programmes are offered within the teenage years; and at 19 to 24 years supporting young people as they move into adulthood and become more autonomous or require support in managing their health and care needs.

Figure 3 describes universal health and wellbeing reviews and suggested contacts as part of overall support 0 to 5 years, detailing key aspects at the following stages:

- antenatal health promoting review

- new baby review

- 6 to 8 week review

- 3-month contact

- 6-month contact

- 1-year review

- 2 to 2 and a half year review

Figure 3. Universal health and wellbeing reviews and suggested contacts as part of overall support 0 to 5 years

Figure 4 describes universal health and wellbeing reviews and contacts as part of overall support 5 to 19, or 24, if appropriate, including:

- 4 to 5 year old health needs review

- 7 to 8 year old health needs contact

- 10 to 11 year old health needs review

- 12 to 13 year old health needs review

- school leavers post-16 health needs review

- transition to adult services

- 18 to 24 year old health needs review

Figure 4. Universal health and wellbeing reviews and contacts as part of overall support 5 to 19, or 24, if appropriate

A needs-led approach

All services and interventions should be personalised to respond to children and families’ needs across time. For most families most of their needs should be met by the universal offer, while more targeted and specialised evidence-based support will be provided as early as possible.

No child left behind (PHE 2020) and Childhood Vulnerability in England (Children’s Commissioner 2019) look at broader evidence and context for individual children, their families and the communities in which they live that make it more or less likely that vulnerability and adversity in childhood has a lasting impact on their lives. It advocates a holistic, multi-agency approach to addressing inequality and the broader causes of vulnerability and wider determinants which might otherwise be overlooked and may be relevant to commissioning and provision of health visiting and school nurse services.

The universal reviews provide opportunity to support personalised or tailored interventions in response to individual or family need, using health visitors’ and school nurses’ specialist public health skills and clinical judgement to work with the child and family or young person to determine and address needs. They also work collaboratively with partners to deliver evidence-based interventions, protect children and keep them safe.

COVID-19 restrictions have impacted provision of 0 to 19 services, including the need for virtual contacts or pausing of some services. Developmental delays, issues relating to perinatal mental health, safeguarding concerns or detection of any early warning signs of vulnerability may require stronger risk management processes and case load assessment to prioritise those families with higher needs. Commissioners and providers may wish to consider development of a recovery plan in partnership with other agencies to support multi-agency support, monitoring and evaluation. Recovery planning should consider vulnerability in prioritisation, including:

- children and young people who may be at high risk for clinical reasons

- those with formal or legal support in place

- those at higher risk due to wider determinants of health and other factors that can lead to poor outcomes

Figure 5 describes an approach to identify and meet ‘perceived, expressed and assessed need’ to improve outcomes, by defining the categories of perceived need, expressed need, assessed need and levels of vulnerability.

Figure 5. An approach to identify and meet ‘perceived, expressed and assessed need’ to improve outcome

High impact areas

The High Impact Areas, with additional information for maternity, provide an evidence-based framework for those delivering maternal and child public health services from preconception onwards. They are central to the health visitor and school nurse delivery model. These have been refreshed and contain new evidence, policy and suggested additional material to support implementation.

Health visitors lead the Healthy Child Programme 0 to 5 and the 6 early years high impact areas:

- supporting the transition to parenthood

- supporting maternal and family mental health

- supporting breastfeeding

- supporting healthy weight, healthy nutrition

- improving health literacy; reducing accidents and minor illnesses

- supporting health, wellbeing and development: Ready to learn, narrowing the ‘word gap’

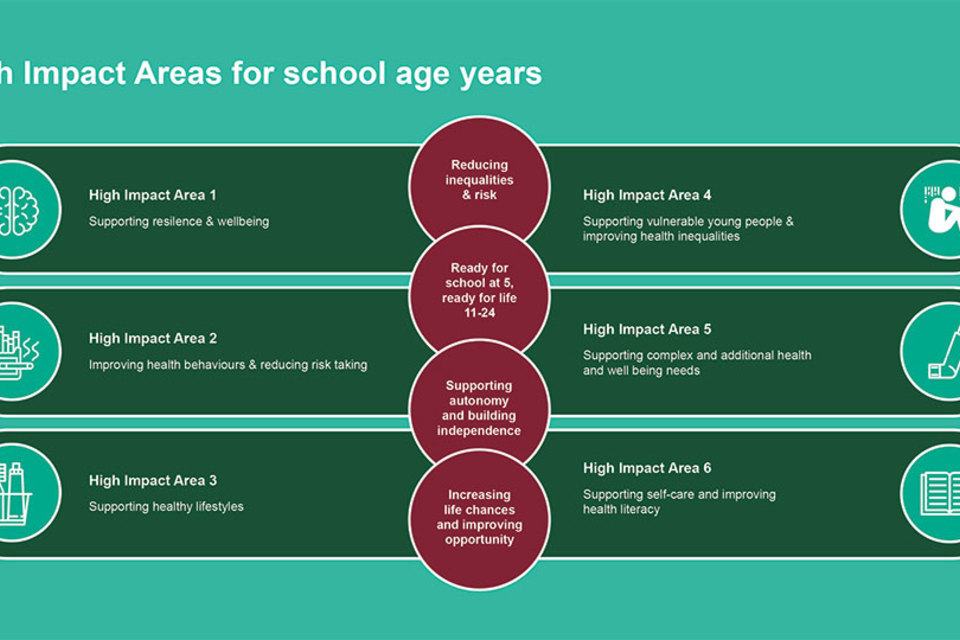

School nurses lead the Healthy Child Programme 5 to 19 and the 6 school age years high impact areas

- supporting resilience and wellbeing

- improving health behaviours and reducing risk taking

- supporting healthy lifestyles

- supporting vulnerable young people and improving health inequalities

- supporting complex and additional health and wellbeing needs

- promoting self-care and improving health literacy

The wide range of issues covered by health visiting and school nursing services are difficult to quantify due to the diverse needs of individuals, families and communities. Taken together, the High Impact Areas describe areas where health visitors and school nurses can have a significant impact on health and wellbeing, improving outcomes for children, young people, families and communities. These High Impact Areas do not describe the entirety of the role and of the health visiting and school nursing services.

Figure 6 lists the 6 high impact areas for early years and how they relate to the 4 overarching aims for early years:

- focusing on preconceptual care and continuity of carer

- reducing vulnerability and inequalities

- improving resilience and promoting health literacy

- ensuring children are ready to learn at 2 and ready for school at 5

Figure 6. High impact areas for early years

Figure 7 lists the 6 high impact areas and how they relate to the 4 aims for school age children and young people, namely to:

- reduce inequalities and risk

- ensure readiness for school at 5 and for life from 11 to 24

- support autonomy and independence

- increase life chances and opportunity

Figure 7. The high impact areas for school-age years

Conclusion

The model and High Impact Areas are designed to support local commissioners and providers to deliver the Healthy Child Programme effectively and efficiently, ensuring the safety and individual needs of children and families are central to the model. Whilst health visitors and school nurses will lead the programme, partnership working, and collaboration is fundamental to responding to the needs of children and young people.

A place-based, or community-centred, approach should support development of local solutions drawing on all the assets and resources of an area, integrating services and building resilience in communities so that people can take control of their health.

References

The NHS Long Term Plan, 2019

Maternity Transformation Programme

Transforming children and young people’s mental health provision: a green paper Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), Department for Education (DfE), 2017

Childhood obesity: a plan for action, chapter 2, DHSC, 2018

Vulnerability in childhood: a public health informed approach, PHE, 2020

Childhood vulnerability in England, Children’s Commissioner, 2019

Healthy child programme 0 to 19: health visitor and school nurse commissioning, PHE, 2018

Supporting the public health nursing workforce: employer guidance, PHE, 2018

Health matters: community-centred approaches for health and wellbeing, PHE, 2018

Working together to safeguard children: statutory guidance, DfE, 2018

Universal health visiting service: mandation review, PHE, 2017

Relationships and sex education and health education, DfE, 2019