Independent end-to-end review of online knife sales (accessible)

Updated 26 February 2025

31st January 2025

1 Foreword

Pooja Kanda – mother of Ronan Kanda

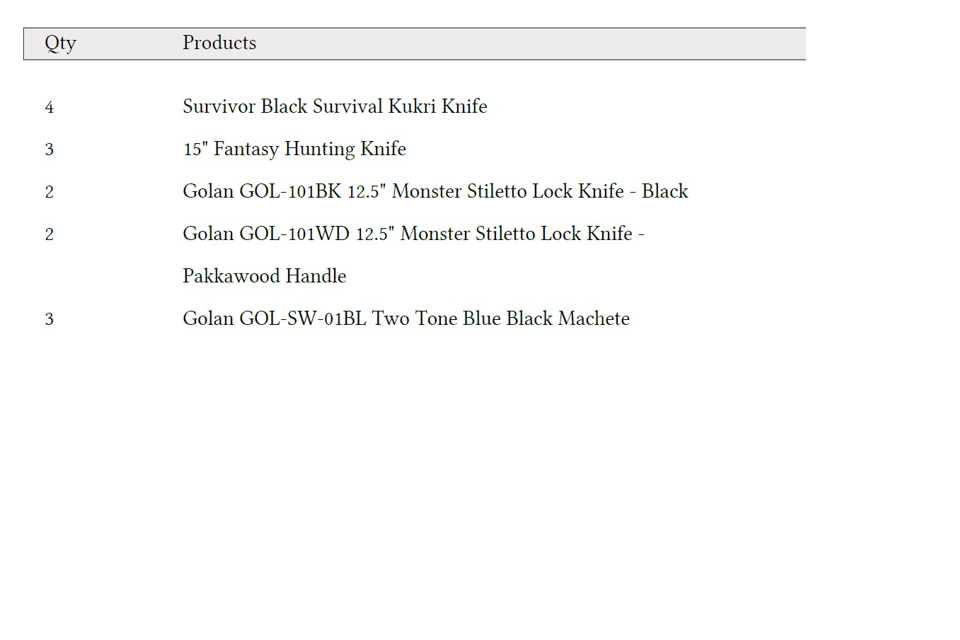

On the 29th of June 2022, my world was shattered when my beloved only son, Ronan, fell victim to a horrific attack in broad daylight. This senseless act of violence was tragically the result of mistaken identity. Ronan suffered devastating injuries: his heart was pierced 17cm deep and his abdomen 20cm deep with a deadly ninja sword. The weapons used in this brutal attack were alarmingly easy to obtain. The perpetrators, Prabjeet Veadhesa and Sukhman Shergil were only 16 years old, they ordered online, the twin set ninja swords and jungle machete from a website and collected it from the post office on the very day of the attack.

The 2023 court trial exposed a series of alarming failures. Prabjeet Veadhesa, the perpetrator, was revealed to be an underage arms dealer who used his mother’s bank details and identification to acquire an arsenal of lethal weapons, all within 6 months before killing my son. The trial highlighted the shocking ease with which Veadhesa acquired these dangerous items, with no age verification or questioning at any stage of the process. This lack of oversight extended to the absence of any inquiry into why an individual would require such an array of deadly weapons. The systemic failures in regulating the sale and distribution of these items ultimately culminated in the senseless loss of my son, leaving a family devastated and a community in shock.

I believe stricter regulation of these lethal weapons in our society will create necessary barriers and reduce the glamorisation of tools designed solely to kill or gravely injure. Banning such weapons demonstrates the government’s commitment to public safety and is crucial in preventing these arms from falling into the wrong hands, sparing other families the pain we’ve endured. My son’s death should not have been the catalyst for exposing these systemic failures. The Post Office must recognise the critical importance of thorough ID checks. This retailer has not only produced the sword that took my son’s life but has also manufactured weapons that have caused suffering to countless others. Sellers, buyers, and distributors must assume greater responsibility for their role in this deadly trade.

After our findings, my daughter wrote to the owner of the website which sold the weapons, whose response was, ‘Swords are collectors’ items. Our customers buy these to keep at home. Just like people collect stamps.’ He blamed the laws and said he wasn’t doing anything wrong. My pain meant nothing to him; he was going to continue selling these weapons and help other murderers with easy access to the bladed articles. I was broken but not lost; I was not going to stay quiet, and we directed our fight to bring about stronger laws.

The government and people in positions of power must ensure laws are being adhered to and that strict procedures are in place to prevent more innocent lives being lost at the hands of lethal weapons. We must constantly think of new ways to implement stronger laws and prevent deadly weapons on our streets.

Stephen Clayman - NPCC Knife Crime Lead

The proliferation of and accessibility to knives has become of great concern, particularly when they fall into the hands of children and young adults. Through social media, we see videos of knife fights in the street, not only causing potential serious injury or death, but having an impact on communities too. The dreadful events in Southport in 2024 have left so many of us shocked and appalled and my heart goes out to all those families who have lost loved ones, or who have suffered life changing injuries and are affected by this. Whilst all of this is not an everyday occurrence, it is, nonetheless, disturbing. Over the past 18 months, my national knife crime working group has been uncovering the harsh reality of how easy it has become to obtain these knives from online marketplaces.

As the National Police Chiefs Council lead for knife crime, my portfolio’s mission is to understand where policing can add value to tackling the issues relating to knife enabled crime. Policing will not mitigate the issues alone and in many areas the police should take a supportive and not a lead role, as other agencies are far better placed to do so. However, there are some very clear elements that wider law enforcement can lead and develop.

To be clear, understanding and dealing with the complex factors behind why someone chooses to carry a knife and then potentially cause harm to others is essential. However, tackling the supply of knives is one important part of the overall mission. We must continue to focus on reducing the availability and ease at which some knives can be obtained, particularly through online sales. Traditional ‘bricks & mortar’ shops will often offer better safeguards and a means of testing their effectiveness through mechanisms like test purchasing, but even more can be done here too.

The review highlights two aspects of online sales; the first relates to regular online retailers, who are official businesses and registered as such. Most of these retailers do operate within the parameters of the existing law. There are however serious flaws in the system, particularly with age verification at point of sale and delivery. This can leave sales vulnerable and reaching those underage or those who wish to circumvent the law in other ways by using social media platforms to sell to others.

These ‘grey markets’ are used by individuals willing to bulk buy knives, prohibited or otherwise and sell indiscriminately across their social media accounts and peer networks. Police have already taken action against a number of them, but the law needs to be stronger here. Our goal must be to reduce their presence on these platforms in the first place and look at how effective existing legalisation is to tackle this, certainly in light of the Online Safety Act (OSA). The review team has had the opportunity to engage directly with social media and technology platforms and have got a sense of the way they operate. They have an over-reliance on their global policies to operate here, which is not sufficient. The OSA will ensure that they must focus more on protecting harmful content from UK users, but there is further work necessary with this sector and there are loopholes here in respect of knife sales.

The review ultimately makes a series of recommendations, some of which can be tackled immediately, like strengthening age verification through a move to buyer identification at sale and delivery. Other aspects, such as regulating the knife sales industry and grey markets needs change too, but some of this will take longer given the consultation required to make the changes. It may be possible to deliver some of these recommendations incrementally, concentrating with online retailing first, before turning to the more traditional ‘bricks & mortar’ retailers.

I have no doubt that the recommendations, if carried out, will very quickly make a difference, especially to the UK market. There is, however, a risk that overseas markets will become more dominant, so extra vigilance will be required moving forward to monitor how knives (including prohibited weapons) are imported. This will require more detailed work with government, industry and partners to further examine the complex processes that need to be understood better if we are to tackle effectively.

Ultimately, we cannot stand by and do nothing.

Commander Stephen Clayman

NPCC Knife Crime Lead

2 Executive summary

2.1 Introduction

Between 2020 and 2024 the number of violent and sexual offences involving a knife recorded by police forces in England and Wales has increased. New and more stringent legislation has limited the availability of larger and more dangerous knives. However, advancements in technology, transport and globalisation have opened the door to new knife markets, instantly available to people through the internet. In response to this growing threat, the Home Office commissioned an independent end-to-end review of online knife sales to look at the sale and delivery process crucial to individuals obtaining knives online.

This report aims to deliver a holistic view of the process of online sales within the UK and from abroad, taking views from key stakeholders across each area highlighting best practice and issuing recommendations on improvements. The extent of the review covers the following:[footnote 1]

- An understanding of the different ways a knife is sold online and delivered within England and Wales. This will cover companies based in the UK and imported by companies based outside the UK.

- The processes followed as part of the online sales process, from the point of sale through to the actual delivery or supply of the knife.

- Whether law enforcement has effective legislation and whether legislation is applied correctly.

- The effectiveness of measures currently used by businesses and organisations to prevent the sale and delivery of knives online to under 18s and the sale of prohibited weapons.

- What gaps and deficiencies exist in current processes and procedures used by online sellers, online marketplaces and companies, delivery companies, enforcement agencies and within existing knife legislation.

- Examples of best practice are being used by online sellers and delivery companies to prevent the sale and delivery of knives to under-18s and the sale of prohibited weapons.

- What recommendations should be made to strengthen processes and legislation relating to the online sale and delivery of knives to more effectively prevent the sale and delivery of knives to under-18s and the sale of knives listed as prohibited offensive weapons.

Throughout this review, the voices of victims and their families affected by knife crime is uppermost in our thoughts. Their experiences offer the true value of why this review is necessary and tackling the availability of knives is increasingly important. The recommendations to follow in this report are made with these victims and families at the forefront, ensuring that each one is balanced to increase public safety and ensure fewer people have to experience the grief and injustice that so many families already feel.

2.2 Methodology

Both qualitative and quantitative analysis has been used throughout this report. In order to maximise the reach, three main methods of data collection were used, as outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Research Methodology and Sample Groups

Online surveys

Online Surveys sent to:

- Law enforcement

- Crown Prosecution Service

- Voluntary sector

- Border Force

- Carrier/Courier services

- Retailers

Surveys ran during the months of October 2024 and January 2025.

The surveys consisted of a mixture of closed questions and open-ended questions designed to gather examples of good practice and more detailed viewpoints.

Consultations

Between October 2024 and January 2025, interviews & consultations were held with various stakeholder groups across the online sales network inculding:

- Online marketplaces, social media and search engines companies

- Senior UKBF representatives

- National Trading Standards

- Ofcom

The data from these was analysed and anonymised in many cases for inclusion in this report.

Quantitative analysis

Quantitative analysis was carried out using published data from various sources including:

- ONS - published crime data

- MoJ - Outcome and sentencing data

Trading standards produced data examining the failure rate of online retailers against age verification processes.

The survey participants were not randomly selected and may not reflect the views of those who did not participate. The qualitative findings presented are solely the perceptions of participants; they may not reflect wider experiences of all individuals working in these organisations. All data is likely to be affected by personal biases of the participants. Due to the time constraints involved, Freedom of Information Requests were not used throughout this process.

2.3 Key findings

Knife use and prevalence in crime

Knife crime as recorded by the Office of National Statistics (ONS) has been rising between 2020 and 2024.[footnote 2] This increase is recorded following the coronavirus pandemic in 2020 which prevented many from engaging in activity outside of their home. The rise recorded has almost reached pre-pandemic levels, however hospital visits as a result of knife injuries haven’t risen at the same rate. Knife crime is recorded in two main ways - selected violent and sexual offences involving a knife and knife possession offences, neither of which record the type of knife involved. This is a gap which leaves the prevalence of types of knives involved in crime uncertain and relies on force level data obtained through freedom of information requests. There is no obligation to record this data and as such, many forces may not have this data available. In a large number of cases, the type of knife may remain unidentified, but it is hard to quantify this without the standardised collection of this information.

Similarly, offences regarding the advertisement and marketing of knives are no longer recorded separately, but the historical data suggests the use of this legislation was sparse. More work is required to determine why this may have been the case, but this report details a dearth of trained investigators able to identify these offences or CPS prosecutors with the knowledge to progress them through the justice system.

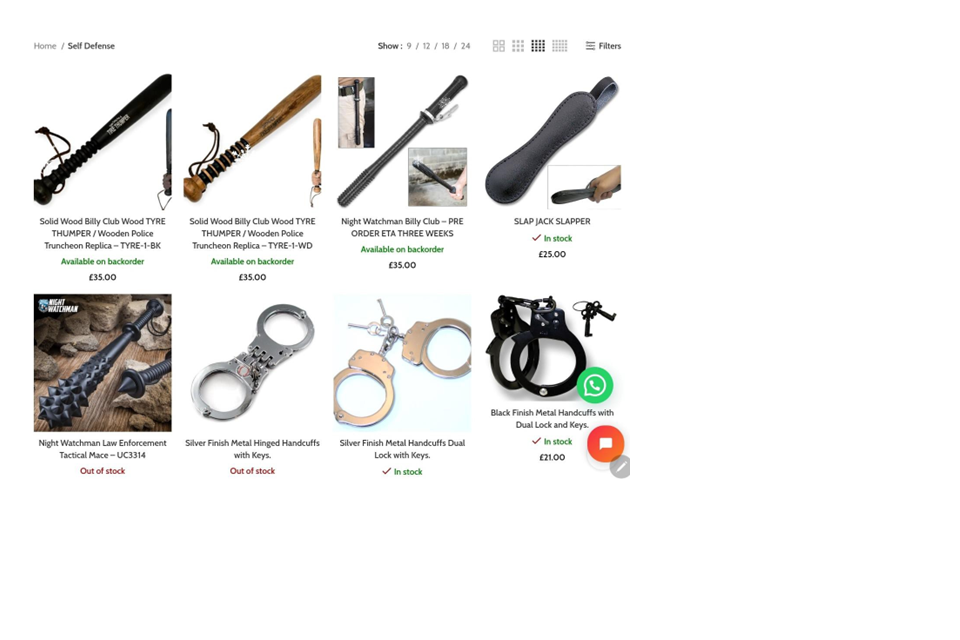

Online knife retailers, sellers, platforms and methodology

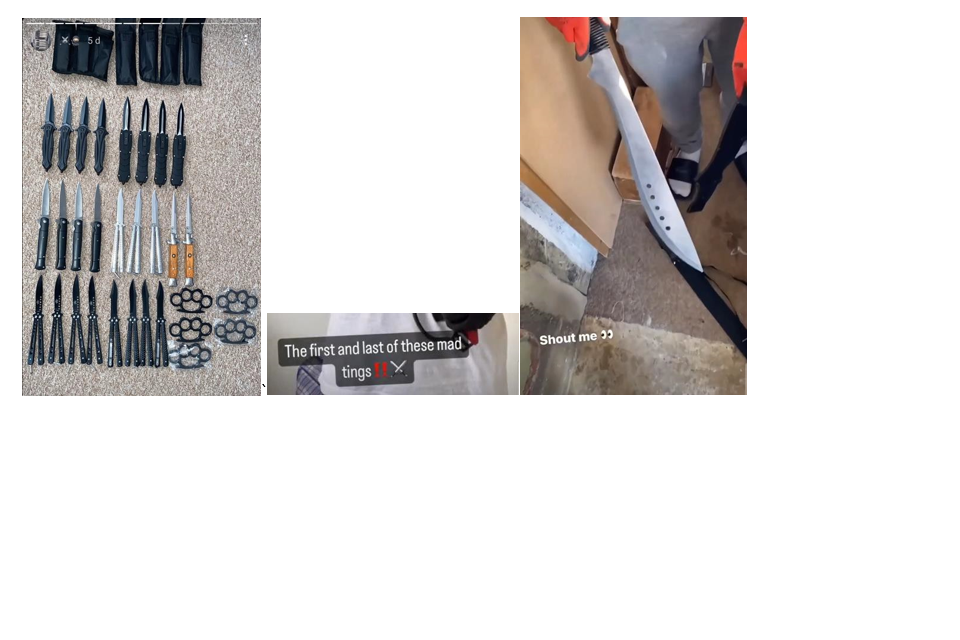

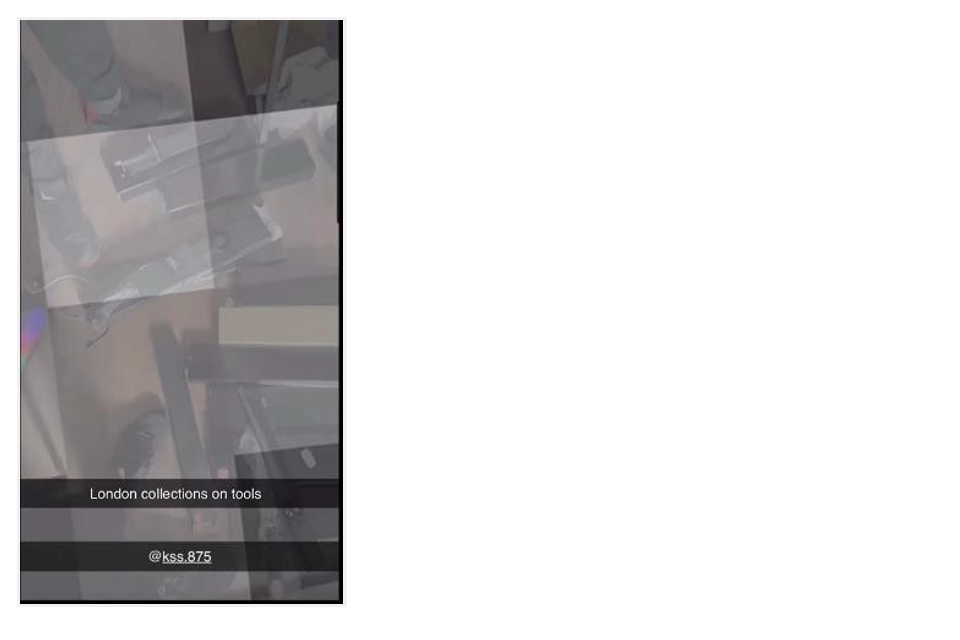

Knives are sold through various methods online, accessible through a variety of different means. There are two categories of seller that are featured throughout this report; retailers and peer-to- peer sellers. Retailers usually host online shops[footnote 3] with the ability to buy knives through their own platform, offering the chance to view and purchase knives using their own implemented systems and processes. Peer-to-peer includes what is described in this report as ‘grey market’ sellers, whose activity may be legal or illegal, but often involves the reselling of knives via social media and sales platforms. This leads to the opportunity for children to obtain knives without any form of age verification or screening at all.

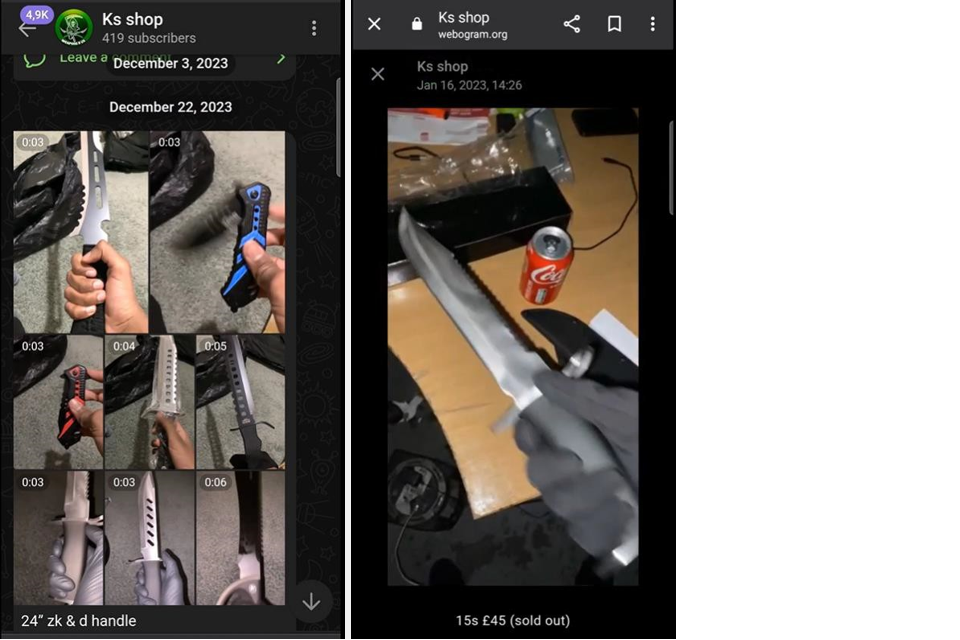

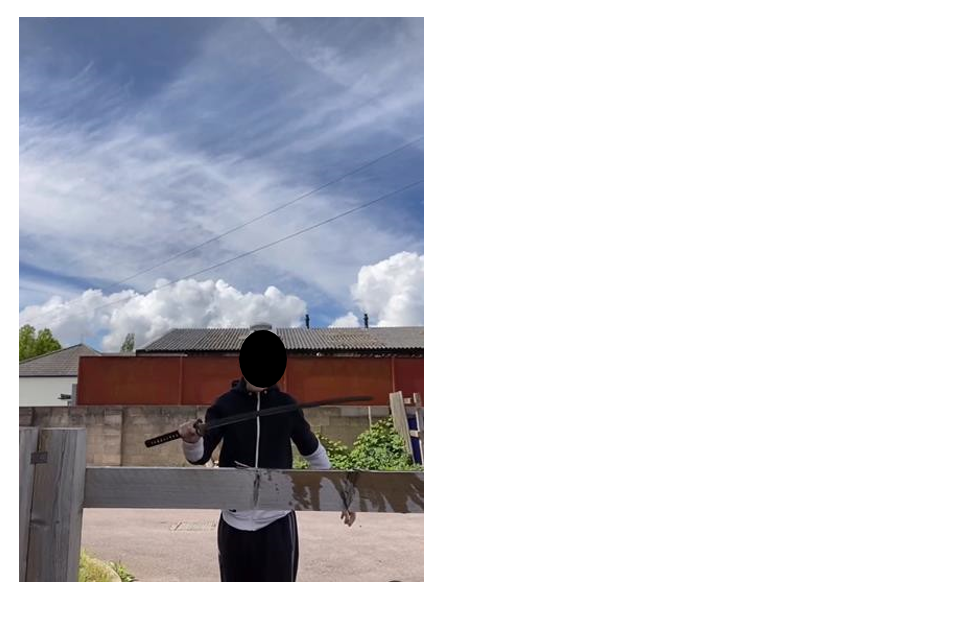

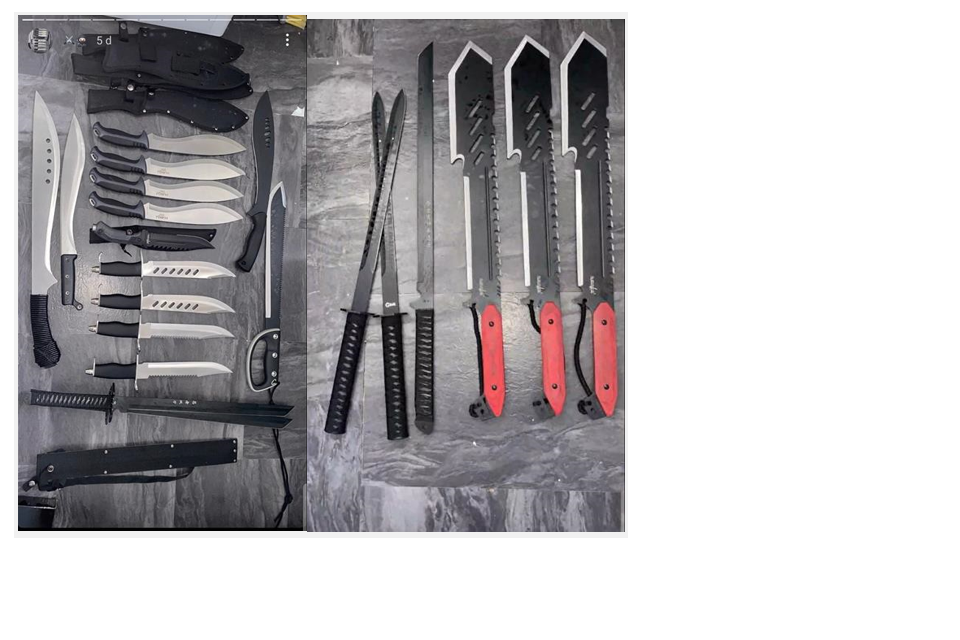

The ‘grey market’ offers the possibility of anonymising the purchase of knives and the case studies suggest they facilitate both legal and illegal sales (contrary to Section 1 Knives Act 1997 and Section 141 Criminal Justice Act 1998).

Knives used in violent offences can be traced back to seller categories of both types, but the grey market often fails to offer the accountability required of retailers operating as registered businesses. The social media platforms that the ‘grey market’ sellers operate on not only give them a level of anonymity, but also allow the possibility of inadvertent advertising to children based on the algorithm used to direct content. The thin and often blurry line between legal and illegal allows sellers to continue to operate online, even following reports to hosts and any action taken against them.

Over a period of time, policing has identified at least fifteen grey market sellers, who it is estimated between them, have sold circa 2,000 weapons. This has been done effectively under the radar and with no effort to check who they are sold to. The sale of knives is not a regulated sector and unlike firearms or alcohol, knives can be sold by anyone, anywhere, provided they are compliant with the Criminal Justice Act 1988, the Offensive Weapons Act 2019 (OWA) and the Knives Act 1997. Many marketplaces have banned the sale of knives, however the use of terms such as ‘cosplay’ or ‘tool’ disguise knife sales which allow sellers to continue selling knives despite the platform’s policy. It is recognised that no system is infallible, but few marketplaces have systems in place that allow for these items to be distinguished from other sales.

Although many knife sellers in the UK abide by the current legislation in place, this becomes more challenging with international retailers who can operate with the appearance of being based in the UK. Some retailers were of the opinion that problems with knife sales are caused by insufficient regulations applying to overseas sellers, but it is acknowledged that the UK does have more restrictions on import than many other countries. Many cited online marketplaces based abroad as a major problem with the availability of knives in the UK.

Age verification – point of sale

Section 141A of the Criminal Justice Act 1988 prohibits the sale of many knives and sharp instruments, and prohibited weapons, to under 18s. Specific defences can be used by sellers if knives are sold to under 18s which include suitable age verification systems, the use of suitable packaging and the provision that it will not be delivered to a locker.[footnote 4]

In proving that the purchaser is over 18, there is no set standard for the seller and the legislation relies on the term ‘likely’ to prevent purchases to anyone under 18. The term ‘likely’ is not defined in law but can be taken to suggest 60-75% of the cases would be true (Fore, J. 2019). In 2019/20, UK Trading Standards conducted a comprehensive test purchase operation where only 3% of the transactions failed an age verification process, but only through the delivery terms and conditions. The limitations on the testing meant that some methods of using false identification and accounts that have a previous transaction where identification was verified remains untested. However, anecdotal cases point towards issues in this area. There are also challenges with RIPA/IPA and the extent that Trading Standards are inhibited by these regulations.

There is no UK standard in age verification and retailers do not have to prove a buyer’s identity before agreeing to a sale. Best practice in this area identified systems of ‘buyer verification’ rather than age verification which means confirming the identity of the buyer through the use of identity documents prior to agreeing a sale. These systems are not beyond abuse but offer a greater level of protection to the seller against underage buyers than other versions of age verification.

Age verification – delivery

The Offensive Weapons Act 2019 (OWA) introduced strict guidance requiring all packages containing a bladed article must be clearly marked as well as age verification at the point of delivery. The onus in these situations is on the seller, with a defence available if they took all reasonable precautions to ensure that the item is not being delivered to a person under that age of 18. Age verification on delivery could not be robustly tested, but examples of practice prohibited under the act are available from across a number of courier companies. This includes some contributors to the review reporting deliveries to both lockers and residential premises. Issues identified by couriers are things such as identification of items based on customer declarations or packaging denoting that the package contains a knife. Retailers face an additional cost when requiring age verification and as such retailers packaging and shipping knives paying for this service would have a defence under the act. The ‘grey market’ rarely use shipping that complies with the OWA and relies on face to face, unmarked shipping and locker boxes to complete their sales.

Many couriers stated that trust was an important part of identifying whether a knife is present for a particular delivery. The processes across the couriers are not standardised and data around the misuse of courier services is not shared in as much detail in order to identify any offenders. Like knife retailers, couriers are not regulated and an individual could start a courier service with no resources or systems in place. The lack of governance around this makes deliveries from those using these companies harder to detect.

There are some systems in place for high value items, with retailers sometimes choosing to use couriers that allow for a pin system, in which a pin code is needed to complete delivery, but these are not currently widely used for knife deliveries. Ideas have been put forward from couriers for similar systems that could be used for ID verification, but it is unknown whether this could fulfil the requirements of the OWA without further exploration.

Ultimately, there is a clear need to join up the verified person buying the knife with that person receiving it too. There will clearly be some logistics to work out, but there is a requirement to stop the current flaws in the process.

Sale and delivery from outside the UK

International marketplaces and retailers should follow the same process as retailers and marketplaces in the UK. However, many of the laws in the UK differ from other countries where knife sellers are located. This presents difficulties in enforcing the current law against international retailers. Equivalent laws need to be available in the country where the offence is committed in order to transfer a prosecution to their jurisdiction. It is therefore important when considering regulating online sales to also look at the way goods enter the country and restrictions that could apply in that area.

The primary difference in the sales process is how the knives enter the UK through the borders. Border Force have responsibility for ensuring that prohibited articles do not enter the country, however the volume of packages entering the country is extremely large and the scanning capacity is limited. Therefore, it is not certain that all prohibited weapons can be stopped at the border and a number will come into the UK for onwards distribution and supply. When prohibited bladed articles are found, Border Force notify the relevant police force area of the seizure. The police response is not standardised from force-to-force and the intelligence gained is not always prioritised for action.

This is an area that requires more examination as it is complex, involving a number of agencies and stakeholders. However, as an internal market becomes more regulated, there is a need to watch those who operate outside of the UK. The dark web does not currently feature extensively in terms of knife sales, but again will need constant vigilance over time to react should this change.

Social media and its role in online sales

The grey market is enabled by the access to videos and posts on social media which display and advertise knives for sale online. Sellers do not always overtly label themselves as retailers and use language which is designed to only hint at sales activity. The adverts themselves are often pointed towards larger, more attractive knives and the language used can sometimes contravene s.1 Knives Act 1997. Social media companies do have the ability to scan and remove illegal posts and accounts, sometimes placing positive messaging in its place. This is mainly used for drug sales but there is no evidence of this being used where there is harmful content such as knife display violence, or knife sales.

Many social media platforms do not authorise sales on their platforms unless through specific marketplaces available on their applications. In the main, knife sales are prohibited, but the same issues exist in these spaces as with online marketplaces. When looking at the grey market, typically the sellers do not use marketplaces, but advertise through social media posts and will often move the buyer to another peer-to-peer platform, which is encrypted and unmonitored. Although some platforms acknowledge local legislative restrictions on particular knives, many of the intervention strategies appear to be based on flagging to remove individual pieces of content manually rather than building this in for automated detection and removal. This overlaps with the issue of regulation in that the focus is on prohibited activity and systemic issues, but global policies appear to present a challenge to them when applying UK legislation.

Regulation of online content

Ofcom are the regulator of online services and have provisions enabled by the Online Safety Act 2023 to take action against platforms for failing to remove of specified harmful and illegal content as well as define the standards that social media platforms must adhere to. The onus through the act is on platforms conforming to a standard of self-monitoring and regulation, which in turn can offer Ofcom the opportunity to fine or issue penalties. Ofcom remain committed to combating knife crime online, their supervision team will engage with the largest and highest risk services to proactively address compliance concerns. Ofcom’s role in this area is to drive systemic change rather than manage individual complaints or specific content. This works towards ensuring that platforms have robust governance systems to manage the risk of illegal content or the glamorisation of prohibited knives. Ofcom can test and recommend changes to the algorithms. However, in order to recognise where changes are needed, specific systemic issues need to be identified.

Monitoring and enforcement is inconsistent across platforms and police force areas, which has identified gaps in skills, training and equipment within law enforcement. Law enforcement does not currently have the capability to consistently monitor and refer harmful content to the platforms and subsequently make Ofcom aware of the systemic issues that exist. Many platforms proactively target certain types of harmful or illegal content, but posts relating to the sale of knives is often reactive. Platforms often operate under global policies which do not recognise UK legislation relating to knives. The result of this is the lack of opportunities to explore whether platforms are adhering to UK legislation and as such, particularly for knife sales, content removal or investigation is challenging. Community reporting of illegal or harmful content is equally difficult, with platforms using this system relying on a user’s judgement that content is illegal or harmful, when many of these posts are designed to attract more users to subscribing.

Regulation of online sales

Online sales regulations are currently enforced by Trading Standards and law enforcement. However, there are currently no requirements for licensing or registration to sell or own knives in the UK. There is legislation introduced under the OWA 2019 which prohibits the sale of certain knives and restricts the way that knives are marketed, but UK retailers operating outside of the grey market are generally selling knives lawfully. The challenge lies in the identification of retailers and the obligations they hold when selling knives. If a retailer is operating lawfully, there is no requirement for law enforcement to be informed as to where knives are being sold, particularly when sold in volume or with regularity to individuals. This has created opportunities for the grey market sellers to buy knives in bulk and resell them, potentially ending up in incidents of violence, without detection. Lessons learned from firearms licensing shows that the regulation of the weapons markets reduces the availability and use of weapons in incidents, but it comes at significant cost to law enforcement.

The introduction of a registration system for knife retailers is a measure that could deliver immediate benefits. From a law enforcement perspective, those involved in firearms licencing are open to the registration of retailers as a potential option to regulate sales, but do warn of significant difficulties in licensing individual knife holders if that was ever considered. Unlike firearms, knives have uses in daily life as either trade or household tools and therefore implementing licenses for individuals would be prohibitive with legal definitions of knives being particularly difficult. Other challenges include volume, cost and resources, with licensing teams operating at a net loss across the country. These concerns are shared by this review team and it is not making that specific recommendation. However, at this time though, there are no checks conducted on knife sellers in the same way as firearms dealers to ensure they are appropriate to be involved in the distribution of these items.

Knife retailers have expressed concern around regulation and have pointed to importation as the biggest risk in knife supply. However, case studies have shown UK retailers being the source of knives involved in violent offences. A risk in this area will be businesses moving abroad and as such registration of knife dealers with subsequent offences for selling knives without registration may need to be accompanied by regulations covering the importation of knives. Some retailers would be in favour of importation licenses to that extent.

Traditional shop front (bricks & mortar) retailers

Whilst it’s recognised that this review is focussed on the online sale of knives, when looking at regulating the overall market, it may be necessary to extend some of this to those traditional retailers based in fixed locations on local high streets and beyond. Many are already signed up to responsible retailer guidelines, but these may need to go further so that both online and high street retailers are moving in the same direction. The public will want confidence that if someone walks into a hardware store, or small business, that they will not be able to buy a relevant knife repeatedly over a period of time, without it being noticed and potentially reported. Given the complexity and volume of these shops, further consultation will be necessary to explore the impact and agree implementation timelines if this was agreed.

A prohibited person

The review has highlighted a need to look at the concept of a prohibited person, both in terms of selling and buying knives. There is already evidence of a minority of owners of registered online retailers having previous convictions for violent offences and are wholly inappropriate to be selling knives to others. This is certainly something that works well where firearms are concerned and is a natural recommendation to make.

There is then the question about those either selling knives through a grey market or purchasing for their own use. Again, existing firearms legislation is helpful from a conceptual point of view. Having more robust action against those that have a propensity for violence and/or found in possession of knives is crucial. They (or anyone on their behalf) should not be able to purchase a relevant[footnote 5] knife online and an overall registration requirement, along with border notifications would aid law enforcement in both identifying risk and safeguarding individuals.

Legislation and sentencing

The legislative options open to law enforcement and Trading Standards includes prosecution of sellers of prohibited weapons, sellers marketing or indicating the knives could be used for combat and the sale to under 18s. Also within the legislation is guidance on how knives should be delivered and age verified on delivery. The sales and marketing offences that can be used are not commonly identified in policing and is an area where officers may not come across it in their day-to-day business. As such, the legislation is rarely used and attempts to use it can encounter barriers at the prosecution stage, with those CPS prosecutors contacted never having dealt with a relevant offence. The separation of offence and power to obtain a warrant under s.141 and s.142 CJA 1988 has caused some confusion in courts with warrants sometimes refused on the grounds of s.141 being a summary only offence (low gravity).

The seriousness of the offence as guided by sentencing has an effect on the police response with possession of a prohibited weapon reaching up to 4 years imprisonment, whilst the supply of prohibited weapons is a summary only offence, with up to 12 months imprisonment. This disparity is at odds with other legislation such as drugs where the illegal supply is treated more seriously than possession offences. Difficulties are faced by law enforcement when obtaining data from tech and communications companies in relation to the specified offences above. The majority of these platforms are based abroad and so require Crime Overseas Production Orders (COPO) or Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty (MLAT) applications, which in the main are only available for serious crime and not available for knife offences.

Knife possession and perception

There could be a number of reasons for the increase in knife incidents as recorded by the ONS including accounts from the voluntary sector which point towards the visibility of knives in the public eye. The reality of knife crime may not change, but the images and videos accessible to the public constantly do. The algorithms on social media platforms adjust content to the user, and so if a young person starts watching videos containing knives it may offer more content of the same type. The use of larger more ‘especially’ dangerous knives may cause people who see these images to feel less safe and as such carry a knife themselves. This in turn could mean young people end up viewing and coming into contact with grey market seller accounts or going directly to a retailer and try and circumvent the age restrictions.

Marketing and communications

Search engines and social media platforms often work on monetisation or views to boost posts or websites into the view of the public. This has an adverse effect on young people in that specific adverts or search results may mean that websites selling dangerous knives become accessible. The algorithms within these platforms are designed to tailor content towards the user and therefore searching or viewing content about knives or featuring knives may lead to advertisements for knife retailers being shown to under 18s. Unlike gambling or other regulated industries, there are not enough warnings on the knife adverts despite knives only being available to those over the age of 18. The lack of any warning may mean that websites are visited more often than they otherwise would have.

Conclusion

There is no doubt that much more can be done to reduce harm by all involved in the end-to-end process of importation, sale and delivery of knives, including greater collaboration between policing, UKBF, Trading Standards, private sector stakeholders and others. Information and intelligence is not shared efficiently and there is an inconsistent response to the receipt of intelligence across the board.

In relation to advertising, tech companies ensure that algorithms are in place to deal with other illegal content, but the same focus is not placed with knives. This is an area in which a line cannot be clearly drawn between what is legal and illegal content at present. More focus is required to ensure children are not subject to online content that either advertises or displays knives, particularly when glamorised. However, a systems change across the board is required to reprioritise targeting the availability of knives online and ensure that where they are available, the right tools and intelligence capabilities are given to authorities in the UK to respond to the threat of knife crime. This should include a more effective law enforcement function that sits nationally and coordinates between all relevant enforcement agencies, stakeholders (including regulators) and tech companies.

Overall, this report highlights the need to urgently review the requirements on knife sellers, but this cannot be addressed in isolation. The review has identified a lack of governance and regulation around the sale of knives and knife sellers in general, whether online or otherwise. This raises concerns about the potential for prohibited or particularly dangerous items to be purchased, as well as the risk of such items being obtained by individuals who may use them for any criminality. Many in law enforcement believe that regulating knife sellers is achievable. However, stronger regulation on the UK market alone may push sellers abroad and as such importation regulations for knives may need to be addressed in tandem. The issue of age verification remains a key vulnerability as it is not done to a minimum standard with both retailers and carriers[footnote 6] unable to provide complete confidence in their operating conditions. The lack of minimum standards and poor compliance has led to knives becoming available to under 18s. Where age verification is used, ID is not required in legislation and therefore has left systems open to abuse. This must be tackled now through a standardised and more robust approach.

3 Summary of recommendations and further areas to explore

The recommendations are numbered relating to the order that they appear in the report. The numbering does not represent any priority in the importance of any recommendation over another.

1. Data recording

Improved data recording across Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice including:

a. The types of knives used in offences.

b. The number of recorded offences for sales, marketing and prohibited weapon offences.

c. The criminal justice outcomes for sales, marketing and prohibited weapon offences.

2. Age verification

Age verification at point of sale and point of delivery should change to buyer verification, requiring the provision of identification documents and a necessity for confirmation that the receiver is connected to the buyer.

Further exploration with couriers and retailers around delivery tracking and verification.

3. Couriers

a. All packages to be clearly labelled as containing a bladed item.

b. Age/identification verification to be robustly employed at point of delivery and collection.

Further areas to explore

c. UK couriers to agree to data sharing agreement with UK Law Enforcement Agencies (LEA)

d. Consider implementation of verification PIN reference number to ensure purchaser and recipient are linked. (similar to fast-food order applications)

e. Legal review into s38 and 39 Offensive Weapons Act to ensure implementations across UKBF and courier networks. (Prohibition on delivering to a residential address)

4. Social media and technology platforms

Provisions for the removal of knife related content on law enforcement. Recommended provisions may be:

a. The requirement for social media platforms to remove of prohibited material within 48 hours of police notification.

b. Requires social media companies to provide comprehensive information regarding individuals and companies unlawfully offering to supply weapons and knives online.

c. Greater awareness for UK LEA to refer and request removal of offending content.

Further areas to explore

d. Social media companies must operate a UK policy, taking into account the specific laws relevant to the UK.

e. Search engines to ensure prohibited articles are not promoted or available to UK customers.

5. Knife retailer registration (England, Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland)

Set up a registration scheme for online knife retailers. It may be helpful to further explore increasing the safeguards in place for offline stores in future.

Conditions for the registration may include:

a. Mandatory reporting of suspicious or bulk purchases.

b. Details of buyer to be recorded, retained and made available to UK law enforcement upon request.

c. All marketing material to display clear age verification livery.

d. Registrants will agree to Police and Trading Standards inspection and test purchasing.

e. New criminal offences of selling, offering to sell and marketing knives without registration (triable either way)

f. Unregistered selling of knives is treated more seriously than possession offences.

g. Retailers will be prohibited from the sale of ‘mystery boxes’ ‘mystery knives’ and ‘reduced priced add-ons’.

h. Registered retailer must not be a prohibited person (to be defined).

i. People and premises will be subject to checks for appropriateness to store and sell knives.

j. Extends to any business selling relevant bladed items, including traditional ‘bricks & mortar’ retailers

6. Creation of a prohibited person

Potential options that could apply:

a. A prohibited person would not be able to apply to be a registered knife seller.

b. The ownership of certain types of knives, or knives believed to be for the purpose of use in violence would be prohibited (an offence would be created)

c. Police may have additional powers in relation to the person or known premises they occupy.

d. A prohibited person should not be able to purchase certain types of knives and it is an offence to purchase knives on behalf of a prohibited person.

7. Importation

a. Import licensing scheme to prohibit unlicensed importation of knives and prohibited weapons.

b. Review the knife import tax levy to ensure knives are identifiable.

Further areas to explore

c. Standardise entry routes into the UK for bladed items, restricting use of less intrusive methods.

d. Training and awareness for UKBF in the knowledge and understanding around prohibited knives.

e. Use of cease and desist letters to overseas retailers.

8. Policing, Trading Standards and Ofcom

a. Creation of a central (national) function to allow for information and greater collaboration amongst key stakeholders.

b. Increase law enforcement capability to identify prohibited online sales activity

c. Increase capability to conduct random test purchase operations.

d. Upskilling of law enforcement to disrupt and prosecute grey market activity.

e. Review of current information sharing amongst UKBF, Trading Standards and UK Law Enforcement.

f. Improve data recording for knife retail specific offences and the types of knives used.

g. Adjust the sentencing guidelines of offences related to online sales making all offences triable either way.

h. Work with Ofcom to consider future OSA code changes.

4 Introduction

This chapter provides more detailed background information to the independent end-to-end review of online knife sales. It details the methods of data collection and terms used throughout the report in order for readers to fully engage with the content.

4.1 Background

Between April 2013 and June 2024, the number of selected offences[footnote 7] involving a knife has risen from 26,501 offences over the year to 50,748 offences (ONS, 2024). A drop in offences was seen during the period in which Coronavirus restricted the movement of individuals however, rates of offences have returned roughly to pre pandemic levels. Similarly, possession of bladed and pointed article offences have also been rising steadily since 2009. The recovery of weapons leading to possession offences is largely down to police activity, but the number of stop and searches is significantly lower than 2010 (gov.uk, 2024). Although an absolute causation cannot be drawn from the comparison between the data sets, it could be suggested that there are more bladed articles and therefore it becomes easier to find them.

It has been previously recognised that there was insufficient governance over the sale and delivery of weapons, particularly online which brought forward the introduction of legislative provisions under the OWA 2019. The provisions ensuring age verification at the point of sale and point of delivery made steps towards addressing sales to under 18s, however it is recognised by police and government that the criminal market and under 18s still have access to not only knives, but more specifically large knives and machetes.

The growth of social media, particularly over the last 10 years shows the emergence of new photo and video services, rising rapidly in popularity. Snapchat (launched in 2011), Instagram (launched in 2010) and TikTok (launched in 2016) now have over now have over 4.2billion users combined (statista.com, 2024) with TikTok showing the fastest growth ever in a social media platform. The opportunities for criminal and harmful activity on these services therefore have grown with usage and the nature of these services presenting challenges in accurately determining how much illegal or harmful content there is.

The government has taken steps to address content online through the Online Safety Act 2023, however through the government’s Safer Streets Mission a knife crime action plan has been launched which recognises that knife crime over the last decade has claimed too many young lives. The commitment includes holding tech companies more to account, prohibition of further weapons and strengthening rules to prevent online sales.

In order to help achieve this, an independent end-to-end review of online knife sales was commissioned. Commander Stephen Clayman, the NPCC lead for knife crime was appointed in 2024 to lead this review which was given a three-month timeframe, with findings and recommendations to be completed by the end of January 2025.

A terms of reference[footnote 8] was outlined by the Minister of State for Policing, Fire and Crime Prevention Rt Hon Dame Diana Johnson DBE MP which defined the following key objectives –

To gain an understanding of:

- The different ways knives are sold online and delivered within England and Wales by companies based in the UK and imported by companies based outside the UK.

- The processes followed as part of the online sales process, from the point of sale through to the actual delivery or supply of the knife.

- How law enforcement applies the law in this area.

- The effectiveness of measures currently used by sellers based within the UK, sellers which are based outside the UK and import knives in and delivery companies to prevent the sale and delivery of knives online to under-18s and the sale of knives listed as prohibited offensive weapons.

- What gaps and deficiencies exist in current processes and procedures used by online sellers, online marketplaces and companies, delivery companies, enforcement agencies and within existing knife legislation.

- What examples of best practice are being used by online sellers and delivery companies to prevent the sale and delivery of knives to under-18s and the sale of knives listed as prohibited offensive weapons.

- What law enforcement can do to improve the way that it enforces the law on the online sales of knives?

This report contains the research and findings gathered throughout the review which are used to conclude in recommendations provided to His Majesty’s Government (HMG).

4.2 Aims

The overall aim of this review is to conduct a critical analysis of the online sales process, from knife seller to knife buyer, looking at retailers, enablers, authorities and systems that allow this process to happen. To address this, both qualitative and quantitative reviews have taken place to explore the views and data provided by participants in this process. These include:

-

Sales platforms: An analysis of the different types of platforms where knives are sold, including mainstream e-commerce sites, specialised knife retailers, private websites, social media, and informal marketplaces.

-

Sales processes: A detailed examination of how knives are marketed, sold, and shipped. This includes the methods used for age verification, customer identification, and payment processing, as well as how legal compliance is monitored throughout the process.

-

Delivery mechanisms: The review explores the role of delivery companies in ensuring that knives are delivered in accordance with the law, particularly with respect to age verification at the point of delivery.

-

Enforcement and regulation: An evaluation of how law enforcement agencies, including the police, Border Force, Trading Standards, and the Crown Prosecution Service, apply current laws to monitor, investigate, and prosecute illegal knife sales online. This section also considers the challenges faced in tracking online sales, particularly those originating from international sellers.

The report provides the findings of this research and gives recommendations to reduce the availability of knives to those intent on using them in crime.

4.3 Terms used throughout the report

This section is to clarify the agreed terms used throughout the report.

In this report there will be references to four different types of online sales platforms:

- Knife retailers: Sellers who operate on the open or clear web with a virtual store, and (in the UK) will be registered as a company and pay taxes. Sales are usually hosted and transacted through an independent website managed by the retailer.

- Overseas knife retailers: As above and based outside the UK. These can also include what are known as drop-shipping websites.

- Online marketplaces: An online marketplace is a type of e-commerce website where product or service information is provided by multiple third parties. (Wikipedia, 2024) This allows multiple independent retailers to operate through a single portal. For example eBay, Gumtree and Facebook Marketplace.

- Grey market: This is a term used throughout this report to describe knife sellers who operate outside of the traditional knife retailer or online marketplace model. Sellers are usually private individuals and not a registered businesses, who advertise and transact over social media or sell through their own personal network.

There will also be references to specific knives, either defined by law or otherwise widely associated by certain terms. These terms are defined in this section, but it should be observed that when researching knives, particularly with knife retailers’ terms may vary depending on interpretation:

- Prohibited weapons: For the purposes of this report, prohibited weapons will be limited to knives and bladed articles as defined under Section 141 Criminal Justice Act, revised under Section 47 Offensive Weapons Act 2019. The legislation prohibits the manufacture, sale, hiring, exposing for sale, lending or possession in private of any defined weapon.

- Machete: A broad heavy knife typically used as an agricultural implement in a similar way to an axe or a scythe.

- Hunting knife: Used traditionally in hunting or to prepare game after a hunt. Usually has specific features such as fixed blade with a single sharpened edge on the blade. It may have a curved portion of the blade designed to skin game and also a straight cutting edge. Variants may include survival knives that also have a serrated edge for sawing.

- Kitchen knife – These are knives that come in a large range of shapes and sizes. They can have either blunt or sharp tips depending on their intended use in the kitchen

4.4 Report structure

This report is structured thematically giving information under the headings of the key themes of the review.

The report begins by introducing some of the lived experiences of people where the law hasn’t provided safeguards against serious crime, including the death of loved ones. This includes what charities and voluntary organisations feel about the online sale of knives. It is followed by a summary of the methodology and a chapter detailing how legislation interacts with online sales, as well as how law enforcement agencies approach online sales and delivery. The following chapter will explore the detail behind the processes and enablers of online knife sales. The various markets through which knives can be purchased online will be detailed in separate sub-headings with stakeholders in these areas given an opportunity to express their opinion.

Chapter 7 of this report focusses on the UK as a whole and explores whether collaboration takes place between the stakeholders in each area, whether data is shared and if so, what happens with that data. It will also look at some of the mechanisms that exist with other threats such as County Lines and Money Laundering. Finally, Chapter 8 will offer recommendations that are written to reflect improvements that can be made on various aspects detailed throughout the report.

5 The effects of online sales and knife crime

Where knives are used for violence on our streets, families and communities are left devastated. The risk posed by every knife in the wrong hands is why this review was commissioned, and it is integral to gain an understanding of how these dangerous weapons enter the market, how they are sold and who is buying them. As part of an evidence based approach, this review utilises detailed analysis to uncover what the factors leading to knife enabled offences are. This forms only a small part of a problem solving approach to prevent knives being used in violence. To understand why recommendations may be needed to tighten the policies, collaboration and legislation around online sales, it is important to include some experiences of victims, their families and the investigators in these cases.

Each one of the accounts below has been considered alongside the wider review to provide context to the findings and recommendations. The voices within this section have been drawn through consultation with people affected by knife crime and where it is known that the knife was purchased online.

Victor Lee

Victor Lee, a 17-year-old from Ealing, was tragically murdered on 25 June 2023 near the Grand Union Canal in west London. He had developed an interest in buying weapons online, including knives and crossbows, which he intended to sell for profit. To facilitate these purchases, Victor altered the date of birth on a non-UK passport to appear older. He arranged sales through social media platforms, notably Snapchat which utilised the messaging facility to communicate with prospective buyers to arrange the transactions and share images of available weapons.

Victor was believed to have purchased the knives and crossbows from a number of different sources including online retailers based in the UK and internationally as traditional shops. His primary method of payment was using a PayPal account. Notably he’d not only falsified his online ID submissions to knife retailers but also on his PayPal account to appear over the age of 18.

On the day of his death, Victor met 18-year-old Elijah Gokool-Mely to sell him knives. Earlier that day, Victor had sold a crossbow to Gokool-Mely but during their second meeting, Gokool-Mely attacked Victor, stabbing him twice in the back and once in the chest, before pushing him into the canal. Despite efforts by nearby residents to rescue him, Victor succumbed to his injuries at the scene.

Analysis of Victor’s mobile phone revealed the conversation on Snapchat in the hours leading up to his death and provided insight into a grey market sales operation run by him. Ultimately, once the weapons were in his possession, there was no legislative barrier preventing him from selling them, provided he had age verification processes in place.

The case underscores the dangers associated with the online sale of weapons and the use of social media platforms for such transactions. Victor’s ability to purchase weapons online by simply altering his date of birth, highlights a fragility in age verification processes and at some point these knives and weapons would have been delivered and received by Victor or in some way by a person that could have passed them on. Additionally, arranging sales through social media exposed him to potential risks. The weapons were not always shipped through the post and in this case the weapons were handed over in person.

Detective Chief Inspector Brian Howie commented on the tragedy, stating, “It will forever be a source of regret to me that this vulnerable but independent young man was able to buy weapons online simply by altering the date of birth in his passport.” He further emphasised that Victor’s use of Snapchat to arrange the sale ultimately “sparked the events which cost him his life.”

Kyron Lee

Kyron Lee, aged 21 from Slough, was murdered in Waterman Court, Cippenham, Slough on the evening of 2 October 2022. He was cycling along Earls Lane with a friend when he was struck by a VW Golf which was travelling in the opposite direction and intentionally drove at him. Kyron managed to get up and run off. He was chased by four masked males, all of whom were carrying machetes and long knives. They chased him down and attacked him causing a number of stab wounds. He was fatally injured having been stabbed in the right thigh from front to back, transecting the right femoral artery. The offenders made good their escape in the vehicle and left him to die alone.

A large scale investigation identified all those responsible. Fras Seedahmed (17), the driver, Mohamed Elgamri (18), who inflicted the fatal stab wound, Khalid Nur (20), Elias Almallah (20) and Yahqub Mussa (21) were all convicted on his murder and received life sentences. Mohamed Abdulle, who helped prepared the offenders before they set off, was convicted of conspiracy to GBH with intent.

Kyron and the offenders were part of two groups whose animosity for one another had existed for a number of years. In the months and year before the fatal attack, there has been a number of knife enabled stabbings between the two groups. This sadly culminated in the death of Kyron. The reasons why the group sought Kyron on the day have never really become clear. However, from the levels of preparation they took before the murder, it was clear that they were seeking out members of the other group and came across Kyron.

An analysis of mobile telephone and financial records showed that the group had previously attempted to purchase weapons from an online knife retailer called Knife Warehouse:

-

The previous December that Mohammed Abdulle attempted three times to purchase knives from the company. However, these transactions failed for unknown reasons. Successful transactions were made and it is thought that the knives were distributed throughout.

-

Screenshots of a large number of machetes from this website were found on Khalid Nur’s mobile phone. Further analysis showed that Nur attempted to have items sent to Mohamed Elgamri at an address unrelated to any of the group. Only one knife was ever recovered and this was forensically linked to Nur. Interestingly this was an identical match for a knife sold on the website.

-

Furthermore, the investigation team recovered a video of Fras Seedahmed brandishing a knife in the company of associates. Again this closely resembled a knife for sale on that website.

Detective Chief Inspector Roddy stated, “Although there was no evidence to show that any of these transactions were successful or that this company supplied the weapons used in this murder, it is clear that these companies help enable such tragedies. Robust identification processes are all very well but it is the purpose behind the purchase which is critical. These items may well be advertised for recreational activities, but it would be disingenuous to suggest that this is the intention behind every purchase. The intention here was quite clearly to take another man’s life. The ease by which such dangerous weapons can be secured is alarming. Without more robust checks and balances, such tragedies will continue to happen.”

6 Methodology

The findings in this report come from a mixed method approach of data collection using both qualitative and quantitative analysis.

-

Online surveys with larger groups of contributors.

-

Consultations and interviews with regulatory bodies, tech companies and other contributors where their role in the online sales process is significant or particularly specialised.

-

Analysis of relevant crime statistics and criminal justice data.

6.1 Online surveys with larger groups of contributors

Online surveys were published and sent to a number different groups identified by the review team as having a significant contribution or expert knowledge that would guide the findings and recommendations in this report. The aim was to explore for each contributor, whether they played a part in online knife sales, how significant their role is and the approaches that can be taken to ensure a safer process. All of the surveys in this process were voluntary and anonymised, unless the contributors specifically contacted the review team to endorse the use of their details and submission.

When conducting the surveys it was not possible to achieve a consensus of the entire population of each stakeholder group. Instead, to maximise participation the survey was sent either through relevant contacts that could assist in the wider distribution or to all known respondents. It is acknowledged that there is a wider public view that was not consulted during this review, however the focus on the review was to gain expert knowledge and consult the stakeholders enabling or facilitating online sales.

The surveys and sampling approaches as part of this review were:

-

Online Knife Retailers – These surveys were sent directly to all online knife retailers that were previously invited to a ministerial round table. The survey was also published online for knife retailers[footnote 9] to engage with if they had not been part of the initial round table;

-

Law Enforcement – Surveys were sent through the National Police Chiefs Council (NPCC) chief constables for force engagement. A separate survey was issued to points of contact for the receipt of notifications of prohibited weapons from Border Force;

-

Border Force – There are six Border Force regions and surveys were issued to each of these regions through a senior Border Force contact;

-

Crown Prosecution Service – CPS employees involved in the prosecution of knife offenders and online sellers, sent through a CPS point of contact and distributed internally;

-

Voluntary Sector[footnote 10] – Charities and volunteer groups who support young people involved in or the victims of knife crime. Sent out through the Home Office voluntary sector lead;

-

Firearms Licensing – Police firearms licensing leads who manage the regulation and licensing of retailers of firearms and licensed individuals. Survey distributed through the NPCC firearms licensing working group;

-

Carriers – Courier/delivery companies. Distributed through the Institute of Couriers to all contacts;

Due to the rapid nature of the review, most surveys were open for a minimum period of three weeks between the months of October and December 2024. The questions were designed to ask mostly closed questions with a small number of open-ended questions to gather more detailed thoughts.[footnote 11] Surveys sent to each group were different in order to draw on the specific knowledge and experience of that group.[footnote 12]

All surveys were reviewed and considered as part of the consultation. The below table shows the number of respondents to each survey.

Table 1: Responses by participants per survey group

| Survey Group | Responses |

|---|---|

| Online Knife Retailers | 57 |

| Law Enforcement | 37 |

| Law Enforcement – Response to Border Force notifications | 14 |

| Couriers | 55 |

| Border Force | 17 |

| Crown Prosecution Service | 18 |

| Voluntary Sector | 8 |

| Firearms Licensing | 36 |

The surveys were sent out to a wide section of the participant groups, however the results must be treated with caution as they will not be representative of everyone in that category. It must also be noted that some of the surveys asked for qualitative data. Due to the volume of this data, it is not possible to include every perspective within this review, but instead gives a broader sense of the types of responses with key highlights.

6.2 Consultations with areas where the participant’s role in the online sales process is significant or particularly specialised.

Some of the respondents to this review singularly or through a small group hold a significant role in the chain of online sales. Where this was the case, it was possible to hold a series of smaller consultations to gain an in-depth response. These were semi structured, with the outline objective and questions similar for each participant in the relevant group.

Where possible a briefing document was provided ahead of time in order to gain expert knowledge from within the organisations and provide a fuller response. All consultations, interviews and focus groups took place between the months of November 2024 and January 2025. Table 2 shows the groups that took part in the consultation aspect of the review.

Table 2: Participant groups of the research conducted through consultation

Participant

- Tech sector (social media platforms & search engines)

- E-commerce

- HMRC

- UK Border Force

- Voluntary sector

- Department of Business and Trade

- Firearms licensing

- Police and Crime Commissioners (PCC) and the Association of Police and Crime Commissioners (APCC)

- Ofcom

- National Trading Standards

- Homeland Security Group

- Home Office

- Larger retail marketplaces (importers and retailers)

To provide anonymity, unless agreed with the participants in writing, they are named in groups rather than by organisation. All those who engaged will be listed in the appendices. Although the questions were broadly the same for participants in the same group, as with the survey questions, the questions were changed to suit the expertise and experience of the participant group, therefore the topics of the responses will differ from group to group.

All responses were then collated and analysed by the review team to pick out key areas to include in the review. Internal quality assurance was carried out to ensure the responses to be included were relevant to the review.

Language will be generalised to denote the consensus between the groups of stakeholders. The terms ‘many’, ‘some’ and ‘few’ will be used in the context of –

-

Many – The view was widespread between the groups of participants.

-

Some – There were more than a small number of participants that gave this response but not enough to use the term ‘many’.

-

Few – There were a small number of participants that gave the response.

Where a particular finding is attributed to one organisation, the report will make clear that this is the case, however the organisation will not be named unless previously agreed. In most cases the findings of the surveys and consultations will be combined as many will be based on the same questions.

6.3 Analysis of national crime data, criminal justice data and other data sources

To identify the key trends in knife crime, how it affects communities and the effectiveness of legislation, data was taken from reports published to the general public online. The analysis will present data that will indicate whether it is possible to ascertain the scale of knives purchased online and if not, what data is required to do so.

Quantitative analysis of data

Data was taken from tables published online from the following sources:

-

Office of National Statistics (ONS) crime and justice tables. Crime in England and Wales: year ending June 2024. (ONS, 2024)

-

ONS Homicide in England and Wales: year ending March 2023 (ONS, 2023)

-

Ministry of Justice (MoJ): Knife and Offensive Weapon Sentencing Statistics (MoJ, 2024)

Published data and the quantitative analysis from them provides a key insight into where particular issues exist in knife crime. The cross analysis with MoJ data provides an insight into the effectiveness of the police response and can contribute to area-based analysis. It could also indicate whether police are using the legislative provisions available to them to prosecute knife sellers and other knife offenders. The time periods used in this report are limited and only include the time periods present in the published data.

6.4 Ethics

Whilst undertaking the review, the following ethical principles were taken:

-

Participation: participation in the review was completely voluntary and withdrawal at any stage up to analysis was possible for any of the participants.

-

Consent: information regarding the review, report and data handling was given to all participants. Following this consent was gathered either through participation in consultations, or agreeing to the terms listed at the start of the survey.

-

Anonymity: participants in the review have been assured that their responses are anonymous unless particularly stipulated and pre-agreed in writing. Analysis was conducted at a level in which the participant would remain anonymous and the findings were presented as a more generalised view. Pre-warning was given to those completing the survey to keep responses limited, to ensure that no information that could lead to identification of the individual is included. Some surveys included a question to gather the email address of the participant. It was clear in these cases that this was voluntary and would be for the purposes of follow up questions from the review team.

6.5 Limitations and caveats of the review

Due to the timescales involved in the rapid review, it has not been possible to extend the consultations and surveys wider than has been conducted. Therefore, it must be noted when reading this review, the participant base is limited and may not be representative of the entire group.

Although knife crime affects all forces, some will be affected more than others, which was taken into account when assessing the results of surveys. The qualitative findings across all surveys are only representative of the individual participant and anyone that they have had consultation with in preparation to answer the survey. As such, some individuals within organisations that participated may not share the views and opinions put forward. Despite this, the qualitative analysis provided rich insight into the effect of online knife sales on the participating organisations and the specific roles they can play in order to combat illegal or harmful sales.

The views of the individuals that have taken part in the qualitative and quantitative questioning may not have expressed the findings published in national data sources. This can be attributed to the feelings and lived experience of the participant. It does not imply that this is any less reliable than published data and may give a more localised view than the larger area or national data that has been used.

When conducting quantitative analysis on published data sources, there are some occasions where the data is incomplete or may appear out of date. These can be put down to changes in recording practice or periodic reviews of certain crime types which means the publishing of data is less regular. Where data sources have been grouped together, it has only been done so where a like for like comparison can be made or the trend is comparable from the data. Due to different data collection requirements across different government organisations it has not always been possible to make a direct comparison and some offences or areas within the data may be collecting similar, but not exact matches[footnote 13].

This report does not attempt to create a comprehensive analysis of research in all cases of online sales or government action and should be contextualised within the wider evidence base. This report should be read with the recommendations which derive from the findings in this report.

7 Knives and the law

7.1 Reporting and recording offences of knife enabled crime

The recording of knife crime and knife enabled offences is the responsibility of law enforcement and the offences included go well beyond what appears on the ONS and other data sources.[footnote 14] In order to understand the public perception of knife crime as informed by media sources, it is important to know that the Annual Data Requirement (ADR) for the collection of Offences involving Knives or Sharp Instruments includes only selected offences with specific sharp or bladed instruments[footnote 15]. The number of offences[footnote 16] where knives were used is still low in comparison to the total number of selected offences. Despite the percentage of offences involving a knife or sharp instrument remaining stable, the volume of knife offences has risen and stayed at an increased rate since around 2016. The chart below shows the total selected knife crime offences (left axis) against the percentage volume involving a knife (right axis).

Figure 1: Number of Knife and sharp instrument offences recorded by the police for selected offences, and the total percentages of these selected categories. (ONS, 2024)

Each knife offence will have a number of potential outcomes, however there is no reporting of criminal justice outcomes specifically against knife enabled offences and reports per offence without breaking down into knife enabled offences and other weapons categories. A representation of serious injuries caused by knives could be drawn from NHS data on hospital admissions. The data suggests that serious injuries caused by knives was on the rise before the Coronavirus pandemic with a high of 5,192 knife injury related hospital admissions between April 2018 and March 2019, however it has settled back to volumes experienced in 2014 following the lift on restrictions at 3,801 admissions between July 2023 and June 2024.

Figure 2: Number of hospital admissions in NHS hospitals in England and Wales for assault with sharp objects by age group (ONS, 2024)

This data, for specific offences is separated from knife possession and supply offences which, in most occasions will be generated by law enforcement or partner activity. There are specific offences relating to the possession of knives in public, which work with other offences particularly relevant to the subject of this report.

In terms of the recording of offences particularly relevant to online sales, the primary legislation falls under Section 1 Knives Act 1997 and Section 141 Criminal Justice Act 1988 which covers the unlawful marketing of knives and the manufacture, supply, importation and possession of prohibited weapons. Other knife offences, generally covering marketing offences have not been recorded on the ONS in isolation since 2021, albeit records before then show few offences were recorded by police. From March 2021 these offences were grouped with firearms and other marketing and licensing style offences.

The investigation into the possession of prohibited weapons is recorded on the ONS as a broader category of ‘Possession of other weapons’. There is no detail within that category that allows the extrapolation of offences relating to prohibited knives. There has been a rise in the number of crimes recorded under this category since 2021 which may correspond with the enactment of the Offensive Weapons Act 2019 legislation. This legislation however, is much wider than knives alone and encompasses many now prohibited weapons outside of knives and bladed articles.

Figure 3: Number of other knives offences (ONS, 2024)

Other knives offences

*No data after 2021 due to a change in reporting methodology.

One category that does record the types of knives used in incidents is homicide. This change was made as a result of discussions around strengthening the provisions against ‘Zombie style’ knives following the introduction of legislation under the OWA 2019. It was discovered that there were issues with the classification of knives by police officers, who are not knife experts and deal with many cases where the knife used in incidents was not recovered or reported by a third party. The only clear data set that ensured a more accurate collection of data was homicide and as such the Crimsec7 reporting criteria was changed to include the type of weapon in knife enabled homicides.

In the latest homicide report (year ending March 2023) there were 590 homicides in total, 244 (41%) of those homicides are recorded with the method of killing as a sharp instrument. Of those where the knife is known (192), 53% of offences were committed with a kitchen knife. This figure takes into account all homicides including domestic homicides where anecdotally the number of knives sourced from the kitchen is higher than other categories. The data for the types of knives however, does not distinguish between the location and categories of offence.

Figure 4: Knives and sharp implements used in homicides, year ending (ONS, 2024)

| Type of weapon | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Axe | 1 |

| Prohibited weapon, lock knife, machete, zombie knife | 22 |

| Kitchen knife | 53 |

| Sword | 2 |

| Other knife [note 27] | 19 |

| Other sharp instrument | 3 |

Without freedom of information requests to each force, the outcomes of investigations into the possession and the use of knives in violence cannot be measured. The Ministry of Justice do publish data containing the disposals in relation to knife and offensive weapons offences (possession and marketing offences). There is no breakdown of individual offences within these categories, however using the broader knife and offensive weapons category shows no real change in the percentage of offences resulting in immediate custodial sentences. Roughly one third of those found guilty of an offence under this category receive an immediate custodial sentence rather than another outcome as detailed below.

Figure 5: Percentage of knife offences resulting in different criminal justice outcomes.

*The remaining offences received no judicial outcome (e.g. Acquitted, no further action)