Overview

Published 14 February 2025

On 20 February 2024 we launched a market study into the supply of infant formula[footnote 1] and follow-on formula in the United Kingdom.[footnote 2] This followed our November 2023 report on price inflation and competition in food and grocery manufacturing and supply.

Our final report sets out our conclusions from the market study and makes recommendations to UK, Northern Irish, Scottish and Welsh governments, in collaboration with other organisations, for action to deliver better outcomes for parents who depend on infant formula to feed their babies.

During the market study we have gathered extensive evidence from a wide range of sources to develop our understanding of the market. We engaged with governments, food standards agencies,[footnote 3] Trading Standards Services, the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA), NHS representatives, nutrition and healthcare organisations, national competition authorities and others with an interest in the market. We issued detailed information requests to manufacturers and retailers using our compulsory powers and commissioned consumer research to understand the drivers of parents’ decisions. We tested our emerging thinking, seeking views on our provisional findings and possible measures to address our emerging concerns in November 2024, when we published an interim report and invited responses to this.

Infant formula is a vital part of the weekly shop for many parents[footnote 4] across the UK, who rely on it to give their babies the best possible start in life. Although a large proportion of parents plan to breastfeed their baby, most parents use formula milk at some point.[footnote 5]

This market has a number of specific features that distinguish it from other consumer goods markets. In particular, the market is tightly regulated for public health reasons. Further, parents are often in vulnerable circumstances when they first make choices about whether and which infant formula to use, their brand choice is often based on incomplete or unclear information, and they are typically then reluctant to switch brands. Against this backdrop, manufacturers place significant emphasis on building their brands – including through their willingness to supply the NHS below cost – and differentiating their products to attract parents, rather than competing strongly on price. And price competition between retailers has typically been weak, including because of the restrictions on advertising and price promotion.

Our analysis indicates that these features, in combination, are leading to poor outcomes for parents in terms of the choices they make and prices they pay for infant formula.

Combination of these market features driving poor market outcomes

We consider that a combination of market features, namely, the regulatory framework, patterns of consumer behaviour, and the prevailing ways in which manufacturers and retailers do (and do not) compete in response to these conditions, are leading to poor outcomes for consumers.

We are therefore making a number of recommendations to governments for action to help bring about better outcomes for consumers.

Features of a well-functioning market

In our view, for the many parents who use infant formula, a well-functioning market would have the following characteristics:

-

clarity for parents that all infant formula products meet the nutritional and safety needs of healthy babies and that cheaper products are not nutritionally inferior

-

clarity for parents about the features that differentiate brands and that these are not related to nutritional need

-

easy access to clear, accurate and impartial information that enables parents to come to an early and informed decision, with relatively little effort, about which product(s) best meets their needs and preferences

-

effective competition between multiple infant formula manufacturers to offer infant formula products with features parents can easily interpret and verify, at competitive prices, and an ability for newer entrants to challenge incumbents if they offer a competitive product

-

effective price competition between retailers, with parents easily able to compare retail prices for their preferred product to get the best deal, without undermining governments’ objective to support breastfeeding

-

a well-designed and robustly enforced regulatory regime that supports governments’ public health objectives without undermining – to the extent possible – the functioning of the market as set out in the preceding bullets

Our market study indicates that the infant formula market does not currently display these characteristics.

Measures to improve outcomes in this market

We are making recommendations to the UK, Northern Irish, Scottish and Welsh governments for action to improve outcomes for parents in terms of the choices they make and the prices they pay for infant formula.

We have identified 3 potential routes to improve market outcomes:

Option 1:

-

action: Reduce regulatory restrictions in the market, in particular by allowing price promotions, and by implication some forms of advertising, in relation to infant formula

-

objective: To stimulate greater price competition at both the retail and manufacturing level, bearing down on prices of infant formula products for consumers

Option 2:

-

action: Improve the design, effectiveness and enforcement of the existing regulations to create a more balanced decision-making environment, counteracting the strong and disproportionately influential effects of branding and the vulnerabilities of consumers in this market

-

objective: Help parents make purchasing choices that are more in line with their underlying preferences, empowering them to select lower-priced offerings in the market, where they wish to do so

Option 3:

-

action: Introduce further regulations to cap infant formula prices

-

objective: To place an upper limit on the amount consumers would have to pay for this vital product, and guard against future periods of rapid price inflation

We have rejected Option 3, which would involve more interventionist regulation in the form of price controls, to set a maximum price for infant formula. This would directly limit prices but would involve significant risks, including that lower prices in the market could rise to the level of the ceiling, resulting in some parents missing out on cheaper options on the market. There would also be significant challenges in the design and implementation of such a measure. We are therefore not recommending the introduction of price controls at this time. However, governments may wish to retain this as a backstop option, if our proposed package of measures does not achieve the desired market outcomes within a reasonable timeframe.

We are not recommending Option 1 on a standalone basis at this time for 2 reasons.

First, it is clear that the UK, Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish governments are committed to the public health goal of supporting breastfeeding. From our discussions with them, we also understand that they have concerns that allowing price promotions would risk undermining their important policy goals. While it is not for the CMA to assess the extent of this potential impact, we note and respect the public policy positions of the governments at this time.

Second, given the current market dynamics that we have observed, we consider that there are limitations on the extent to which such measures would lead to better outcomes for consumers without other measures to change consumer behaviour. While allowing price promotions could incentivise retailers to drop prices for certain periods, with consumers saving money, this would address only a proportion of the potential savings consumers could make in this market. Retail margins for these products are not notably high at present, and this measure would do nothing to support consumers in choosing lower-priced brands in the market, which would be a much more significant source of cost savings.

Additionally, while there is a potential argument that allowing retail price promotions would put greater incentives on retailers to push back on cost increases from manufacturers, we have found that retailer buyer power is relatively weak in this market, so this effect is likely to be limited.

We are therefore not recommending that governments pursue Option 1 at this time. However, we note that if action is taken to enable more effective consumer engagement in this market (as we set out in Option 2) and/or governments’ understanding of the appropriate trade-offs between public health and consumer goals were to shift, this may be an option that policymakers wish to explore. We stand ready to assist governments further in that case.

At this point, we are therefore recommending Option 2, which comprises a package of measures to sharpen the effectiveness of existing regulations to maximise the ability of parents to make choices that suit their preferences and budgets. We recommend that governments pursue this package vigorously and in full to maximise the extent to which this market can be expected to operate well for consumers, within the constraints of current public-health oriented regulation.

Taken as a whole, our package of mutually reinforcing measures aims to fundamentally alter the dynamics of competition in the infant formula market to bring about better outcomes for parents in general in terms of the choices they feel able to make and prices they pay for infant formula. These measures provide a necessary counterweight to the combined effects of unintended consequences of existing regulation, the strategies adopted by manufacturers, and the ways in which consumers are inclined to interact with the market. They will do this primarily by creating a situation where parents become more price sensitive and have greater confidence to select less expensive options on the market. This will in turn incentivise manufacturers to compete harder on price, bringing greater downwards pressure to bear on prices.

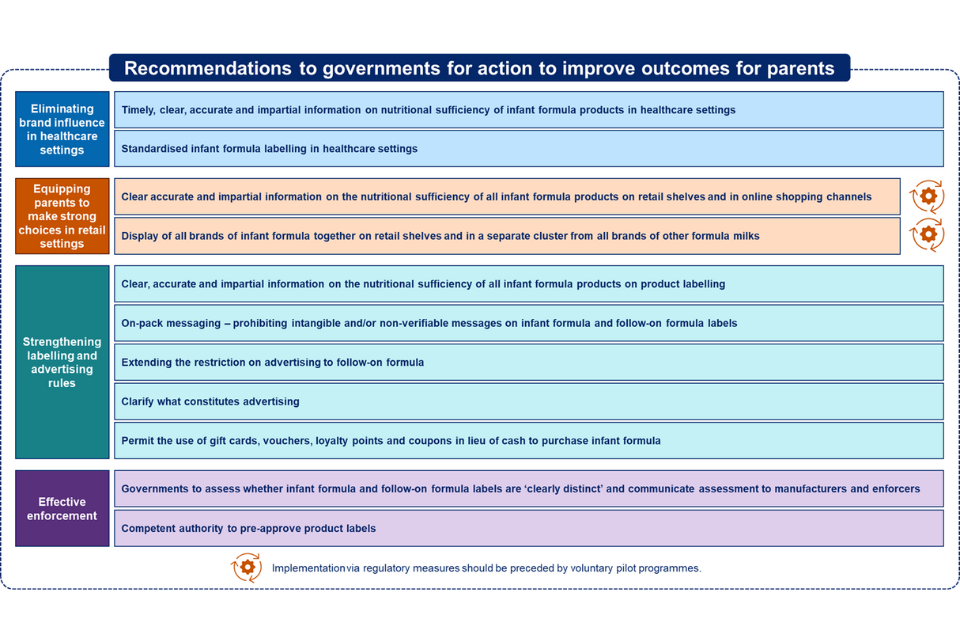

To deliver this fundamental shift, we are making a number of specific, actionable recommendations to governments, falling into the following categories, and illustrated at Figure one below.

Eliminating brand influence in healthcare settings:

-

the provision of timely, clear, accurate and impartial information on the nutritional sufficiency of all infant formula products

-

the provision of infant formula in healthcare settings with standardised labelling

Equipping parents to make strong choices in retail settings:

-

the provision of clear, accurate and impartial information on nutritional sufficiency of all infant formula products on retail shelf-edges and in online shopping channels

-

the display of all infant formula brands together on retail shelves, and in a separate cluster from all brands of follow-on formula, and other formula milks

Strengthening the labelling and advertising rules through:

-

requiring information on the nutritional sufficiency of all infant formula products on product labelling

-

prohibiting intangible and/or non-verifiable messages on infant formula and follow-on formula labels

-

extending the existing restriction on advertising infant formula to follow-on formula

-

clarifying what constitutes “advertising”

-

permitting the use of gift cards, vouchers, loyalty points and coupons in lieu of cash to purchase infant formula

Ensuring effective enforcement of current and updated regulations:

- including strengthening governments’ competent authority role[footnote 6] by introducing a pre-approval process for infant formula product labels

We consider that implementing this package of measures is essential to drive improved outcomes for parents. We therefore strongly encourage governments to act on our recommendations, vigorously and in full. We note however that these options are aimed at shifting widespread and deep-seated patterns of consumer behaviour. While we believe that this package has a strong chance of achieving this, the extent to which it will do so is inherently uncertain. It remains open to governments to consider, additionally, removing some regulatory restrictions including on price promotions should they wish to revisit the public policy position in terms of any impact on breastfeeding. We note in this regard that we have not seen any evidence that infant formula prices influence the decision of whether or not to breastfeed.

If, having implemented our recommendations, governments consider that the impact on consumer outcomes is insufficient, it remains open to governments to consider the backstop option of introducing price controls.

Following publication of our final report, we stand ready to engage with governments and others to explain the recommendations, and to facilitate and support their implementation.

A diagram showing the recommendations to governments for action to improve outcomes for parents. There are 4 categories of recommendations: 1) eliminating brand influence in healthcare settings 2) equipping parents to make strong choices in retail settings 3) strengthening labelling and advertising rules 4) effective enforcement.

-

In Northern Ireland and Scotland in the context of the Nutrition Labelling Composition and Standards Group. ↩

-

Infant formula is designed for use in the first months of life and is the only substitute for breastmilk that can satisfy, by itself, the nutritional requirements of healthy babies until appropriate complementary feeding is introduced. ↩

-

Follow-on formula is a product for use by infants once complementary feeding has started (generally from 6 months), intended to constitute the principal liquid element in a progressively diversified diet. The NHS advises that ’Research shows that switching to follow-on formula at 6 months has no benefits for your baby. Your baby can continue to have first infant formula as their main drink until they are one year old.’ All major suppliers of infant formula also sell follow-on formula. ↩

-

We use ‘parents’ to refer collectively to parents and carers in our report. ↩

-

Official statistics indicate that within 2 months of birth more than 2 thirds of babies are given at least some formula milk. Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (2023), experimental data, Breastfeeding at 6 to 8 weeks after birth, Apr 22 to Mar 23; Public Health Scotland (2023), Infant feeding statistics Financial year 2022 to 2023; and HSC Public Health Agency (2024) Health Intelligence Briefing. Data is for England, Scotland and Northern Ireland ↩

-

Regulations currently provide that no food business operator may place an infant formula on the market unless they have given prior notice to the competent authority where the product is being marketed. ↩