Executive summary

Published 26 July 2022

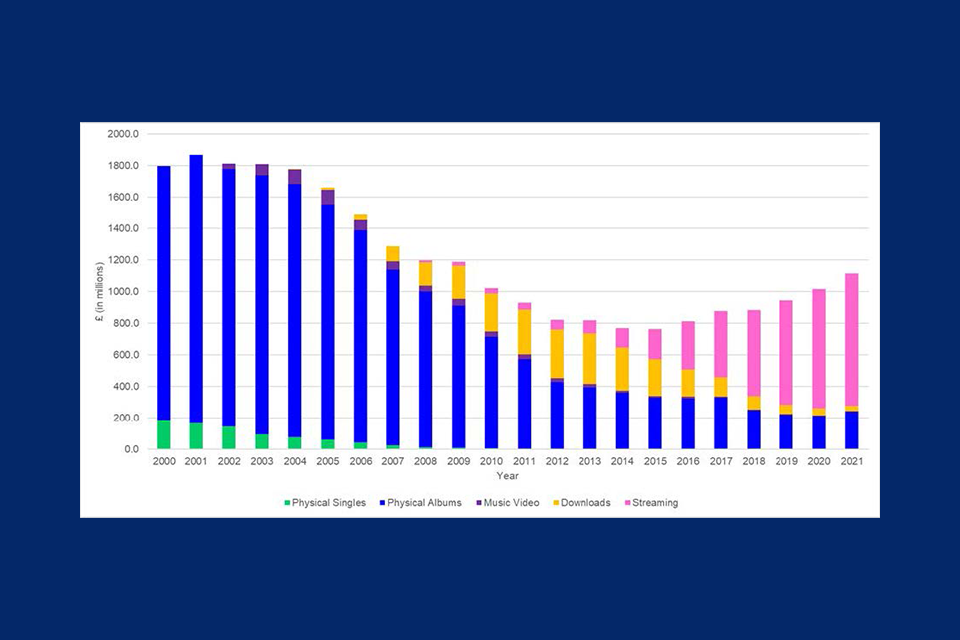

Music streaming has transformed the music industry. Whereas previously consumers would typically own a few CDs or vinyl records by their favourite artists, the rise of music streaming has given consumers easy access to large catalogues of music covering a vast array of genres and time periods for a fixed monthly price (or free, but with ads). Recorded music is now also costing consumers less overall compared to when CDs and other physical formats were more popular, with inflation-adjusted UK recorded music revenues falling by around 40% from £1.9 billion in 2001 to £1.1 billion in 2021.

Consumers have embraced music streaming – in 2021 in the UK there were 39 million monthly active users of music streaming services and there were over 138 billion streams. Streaming is now the primary means for artists and labels to distribute music and has been pivotal in securing the sector’s recovery from piracy. The price for music streaming services for consumers has also gone down in real terms in recent years because the monthly cost of music streaming service subscriptions has generally not kept pace with inflation.

Our study has assessed the impact streaming has had on the music sector and whether competition is working well for consumers by delivering high-quality, innovative services for low prices. Although our primary focus is on consumers, we have also considered the position of songwriters and artists, to consider concerns raised by some stakeholders that the market is not serving creators’ interests sufficiently.

Digitisation had a significant impact on the music industry

The digitisation of music, in its early years, increased the use of illegal filesharing which caused a collapse in music industry and creator revenues as CD and other physical sales declined – inflation-adjusted UK recorded music revenues fell by around 60% from £1.9 billion in 2001 to £0.8 billion in 2015. The introduction of services to enable legal, paid downloads of songs, followed by music streaming, meant that consumers could access the music they wanted legally, and that music companies and creators could monetise their content on digital services for the first time. Today, more than 80% of music is listened to via music streaming services. As a result of the introduction of music streaming services, inflation-adjusted recorded music revenues have increased from £0.8 billion in 2015 to £1.1 billion in 2021, although these revenues remain below their pre-piracy peak.

Streaming also created new opportunities for labels and creators to reach new audiences and has extended the lifecycle for earning revenue from songs. This is a benefit to those creators whose music continues to be listened to, but is not necessarily good for all artists because it means that today’s new music competes with yesterday’s songs for a share of streaming revenue.

UK inflation-adjusted recorded music revenues between 2000 and 2021 by format type

Alt text: Bar chart showing UK inflation-adjusted recorded music revenues between 2000 and 2021. It shows that initially revenues came solely from physical albums and singles. In more recent years, streaming has generated the most revenue. Total revenue dipped in the 2010s, recovering after a low in 2015, but remains significantly lower than at its peak in 2001.

Source: CMA analysis of data provided by the BPI.

Notes: Inflation adjustment using the ONS CPI Index 22 June 2022.

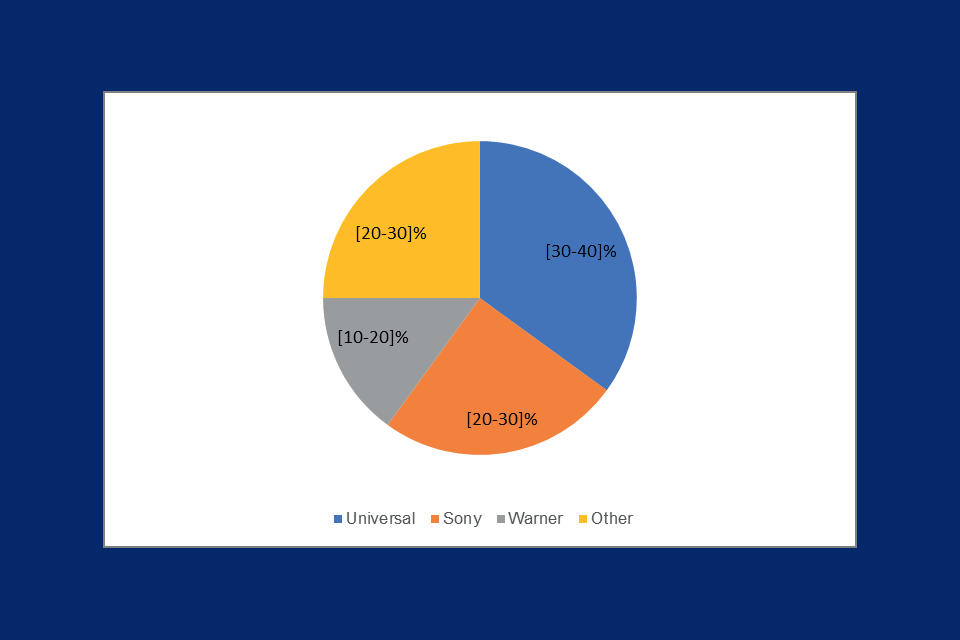

The recorded music sector is concentrated, but the evidence does not show this is driving the concerns raised by artists

The recorded music sector is concentrated, with the 3 major labels holding a combined share of over 70% of UK streams, and this has persisted for some time. This persistent market concentration is one of the reasons why we launched this market study to check whether the market is working well. The market share in terms of streams of independent music companies (indies) has remained steady at around one quarter for several years. This share is very fragmented with only 2 indies having a share in excess of 1%.

Label shares of total UK streams in 2021

Alt text: Figure shows label shares of total UK streams in 2021. These are: Universal [30-40]%, Sony [20-30]%, Warner [10-20]%, and Other [20-30]%

Source: CMA analysis of data from Official Charts.

Notes: This pie chart is for illustrative purposes only. These figures are provided in a 5% range where the figure is below 10%, and a 10% range where the figure is between 10% and 100%. The midpoints of the ranges have been used to provide an illustration of relative size in the market. Where the sum of these midpoints does not equal 100%, we have scaled the pie chart so that the area segments represent the share of the sum of the midpoints.

The scale of the majors and their global reach mean they can offer large advances which attracts proven and successful artists. In turn, this can make it difficult for independent labels to attract and retain artists as they become successful, which can create a barrier to expansion for independent labels.

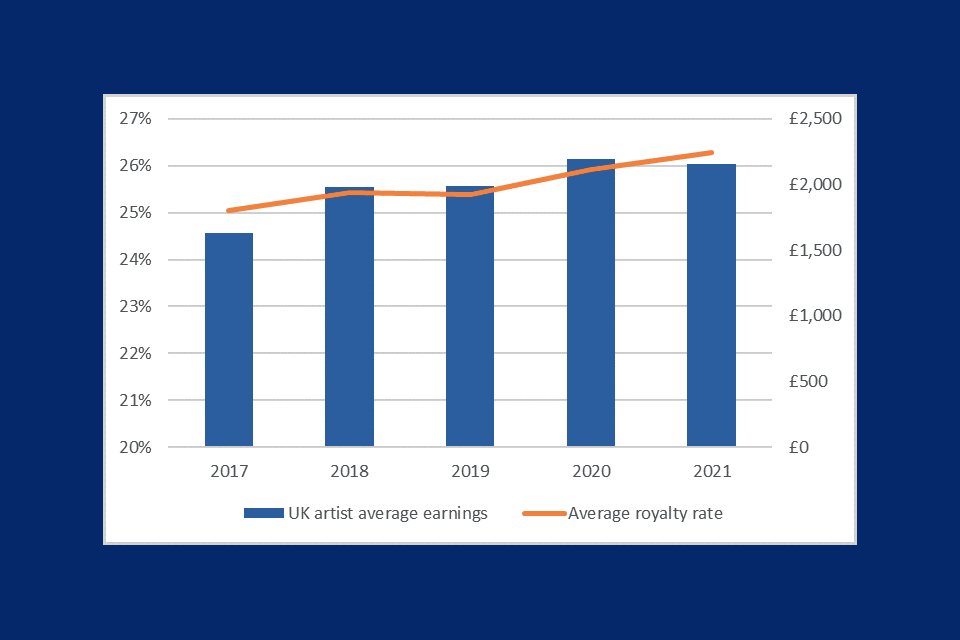

Despite the concentrated nature of the market, there is competition for some artists especially those who are already popular or are particularly likely to be. Competition to sign such artists can be very intense with offers from many labels. Traditional record deals face increasing disruption from alternative models, in particular service deals from artist and label (A&L) service providers, and there are more options than ever for artists to get their music to market. Evidence indicates that new artists today are more likely to be offered higher royalty rates and shorter contract terms than in the past.

Average UK artist streaming earnings from majors and average royalty rates

Alt text: Figure showing the average UK artist yearly streaming earnings from majors and average royalty rates between 2017 and 2021. It shows a rising trend for both average earnings and average royalty rates. It also shows that the average UK artist earned £2,000 from streaming from majors in 2021 with an average royalty rate of around 26%.

Source: CMA analysis.

Our current assessment is that outcomes for artists are driven by factors which are largely unrelated to the high degree of concentration. There has been a huge increase in the number of artists sharing their music and a vast back catalogue made available via streaming. This, coupled with the fact that there is only a finite amount of music a consumer can listen to and a relatively fixed pot of revenue from streaming, inevitably reduces the amount that most artists can earn, even with increased royalty rates. While the majors’ profits have been increasing since the lows of piracy, the current evidence does not suggest that market concentration is allowing the majors to make sustained and substantial excess profits.

The market is challenging for some creators, but more artists are releasing music and they have more choice

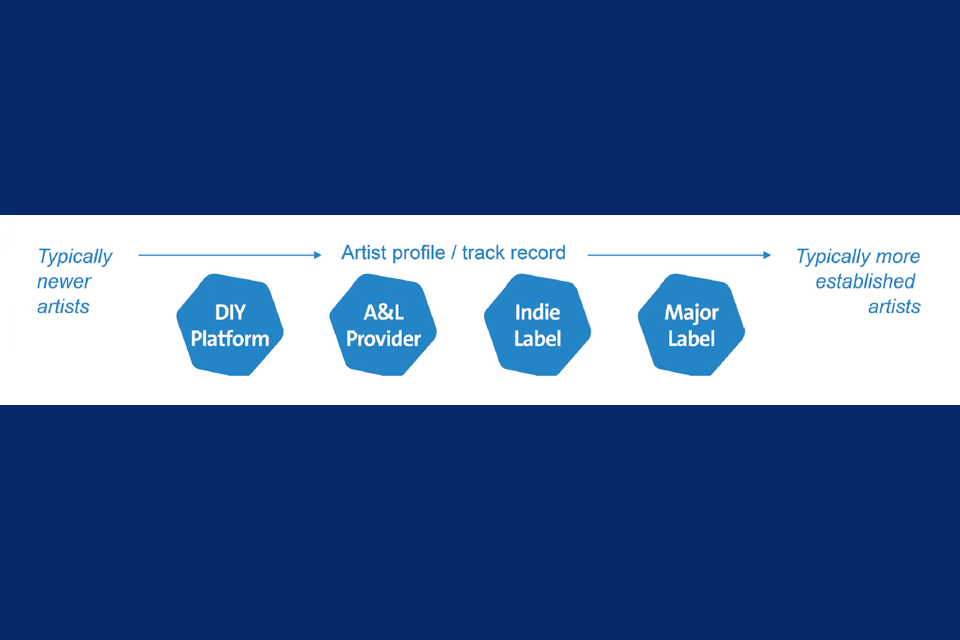

More creators than ever before are releasing music – with the number of artists who stream their music increasing from around 200,000 in 2014 to 400,000 in 2020 – and today they have more choice over how they distribute it. Technological innovation has made it easier to create and record music outside the confines of a traditional music studio, and new services have emerged which enable creators to get their music onto streaming services without the need for a record label. Shifts in technology have also allowed consumers, creators, and music companies to upload content to User-Uploaded Content (UUC) platforms, such as YouTube and TikTok, which gives them an alternative means to share music.

When choosing how to release their music and develop their careers, some artists agree a ‘traditional’ deal with a major record label, which is attractive because it tends to offer higher up-front earnings and those labels have the experience of supporting artists to become commercially successful. However, there are alternatives to the traditional record deal. These include A&L services which offer more scaled down services than that of traditional deals in return for artists keeping a greater share of royalties, or DIY distribution models which allow artists to distribute their own music without label support in return for artists keeping most or all of the royalties. Artists can also seek to build their own fanbase using social media to either drive listening to their tracks on streaming services or use the fact that they have a strong fanbase already as leverage when negotiating a record deal with a label.

Alt text: Figure showing the differences in the artist propositions offered by different options. The figure shows the options as DIY platforms, A&L providers, indie labels and major labels, in that order. It suggests that artist profile and track record tends to increase across these options, with typically newer artists using DIY platforms and typically more established artists at the label end.

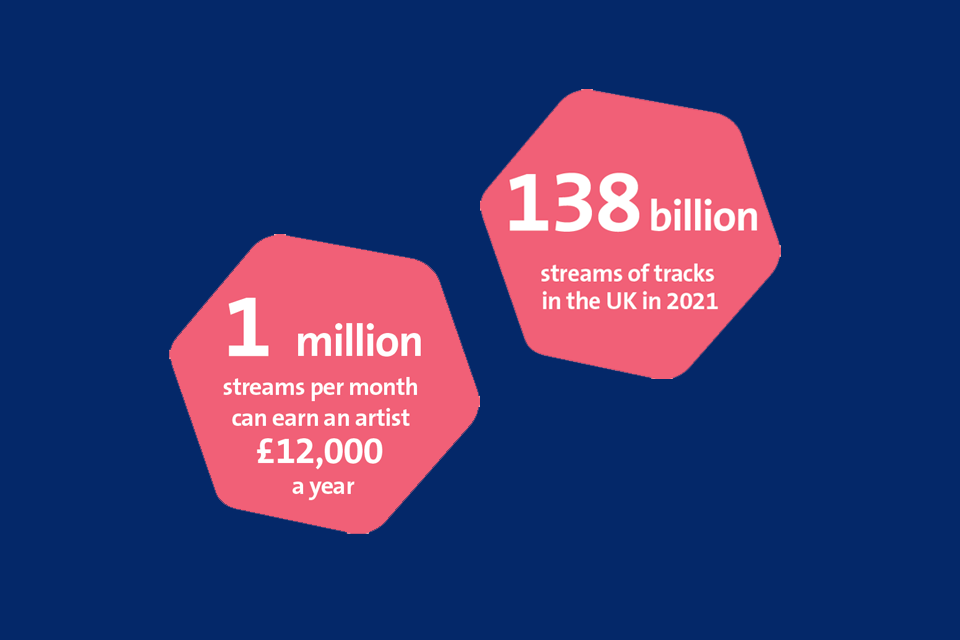

We note that it has long been the case in recorded music that only a very small minority of artists will achieve the highest level of success. Given the large number of streams that occur each year in the UK and the need for a song to be streamed many millions of times to reach the top of the charts, for many artists they will see their songs listened to perhaps millions of times but that not translate into streaming becoming a significant share of their income. Less than 1% of artists achieve more than one million streams per month, which could earn an artist around £12,000 per year.

Alt text: Two hexagons containing text as follows: 1 million streams per month can earn an artist £12,000 a year. 138 billion streams of tracks in the UK in 2021.

Although more artists than ever are releasing music, this does not mean that there are a larger number of successful artists – analysis published by the Intellectual Property Office (IPO) shows that the number of artists reaching one million UK streams per month has increased but remains low at around 1,700 (approximately 1 of every 250 (0.4%) artists who were streamed).

Overall, there have been some positive changes in the market for artists, such as the fact that barriers to entry for releasing music are much lower than they used to be. But this has also led to a very large increase in the number of artists competing for streaming revenues, and as a consequence only a small minority are able to earn substantial revenues.

The evidence suggests that the majors are not suppressing publishing revenues

There are 2 sets of music rights:

- rights in the underlying song or ‘publishing rights’ which includes the music and lyrics; and

- rights in the particular recording of that song, the ‘recording rights’.

Creators may transfer their publishing and recording rights to, respectively, music publishers and record companies. Both rights are needed when streaming a song, so music streaming services must seek licences from both music publishers and record companies. Given the complementary nature of these rights, many music companies (including the majors) have both publishing and recording interests, with the majors leading both sectors. Songwriters and their representatives have suggested that it is financially advantageous for the majors to maximise revenues paid to the recording side of the business and that, as a result, publishing’s share of revenues is unduly suppressed causing harm to songwriters.

As part of our analysis, we have therefore also considered whether the majors operating both record label and publishing arms reinforces their market power or has a detrimental impact on songwriter revenue.

Evidence shows that the share of revenues going to publishers (publishing share) has increased from 8% in 2007 to approximately 12% in 2012, and incremental increases thereafter. Our analysis shows that in 2021 the share of streaming revenue paid to publishing is now 15%. So since 2007 this publishing share appears to have almost doubled. In the most recent period (between 2017 and 2021) there has been a slight fall in the publishing share, mainly due to an increase in the share retained by music streaming services rather than a shift from publishing revenues to recording revenues. However, in absolute terms, overall publishing revenues from UK streaming have grown significantly.

It appears unlikely that any strategy of disadvantaging the publishing business would be beneficial to a major’s business as a whole. If a major were to act contrary to the interests of songwriters by diverting revenues to recording instead of publishing, it would likely impact its ability to retain existing songwriters and compete for song writing talent. The major’s publishing share would no longer be competitive, compared to other publishers, so the major would likely lose songwriters to other publishers.

The current evidence indicates that deals with the music streaming services are largely negotiated separately by the recording and publishing arms, and the evidence we have seen does not suggest close cooperation or cross-influence on financial terms. Record label and publishing businesses are ultimately accountable for securing the best contract terms possible for their respective artists and songwriters.

Overall, the evidence we have seen does not support the allegation that there are restrictions or distortions to competition that are leading the majors to suppress publishing revenues.

Labels could do more to improve the information they provide to artists

Throughout the study we have heard strong concern from some artists and their representatives that they do not get enough information from record labels on how their earnings from streaming services are calculated or how the deals that exist between labels and streaming services may affect what they earn or could earn in future. We heard that artists and their representatives are prevented from seeing contracts between majors and music streaming services due to non-disclosure agreements, which means that they do not know how those contracts affect the overall amount they may earn from streaming.

In general, there are aspects of contracts between record labels and third parties such as streaming services that are not relevant to artists’ understanding of what they are paid, which we would not expect artists to have access to. However, we do expect artists to have relevant information about the basis for calculating their earnings.

Our initial analysis indicates that artists are provided with information, such as number of streams and the rate per stream, which tells them how much they have earned per stream on music streaming services, and we saw some positive examples of labels presenting this information in a user-friendly way. However, this was not consistent across all labels, and we think information could be presented in a more straightforward way with appropriate guidance on how to interpret the data. This will help creators better understand how they are paid for streaming and the sources of their income. We welcome the work the IPO is undertaking on issues around transparency for artists and will share our findings with them to help inform their work.

The evidence suggests that competition between music streaming services is currently working reasonably well for consumers

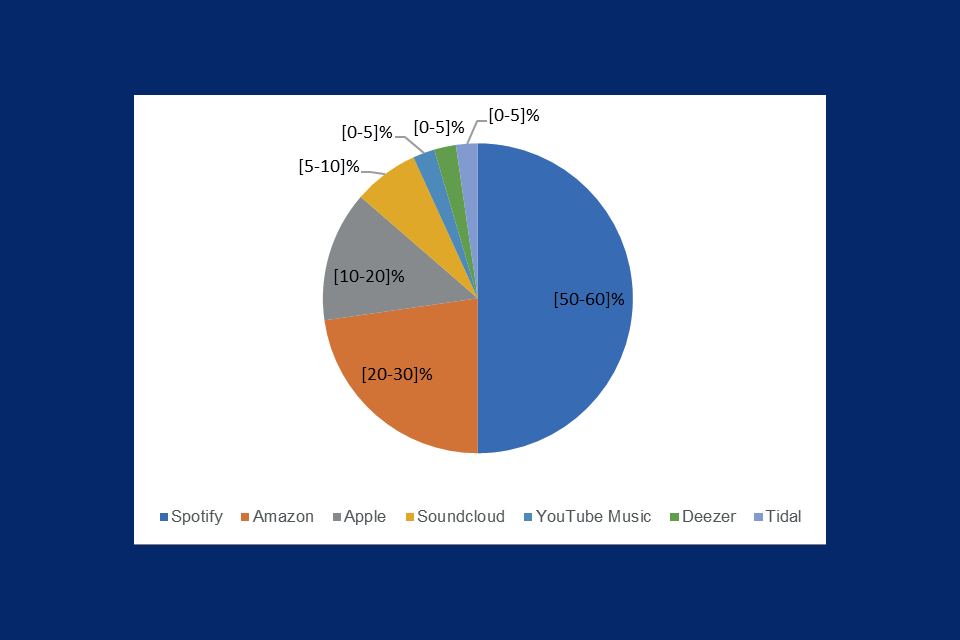

The music streaming services market is concentrated with a few larger streaming servicessuch as Spotify, Apple, Amazon and YouTube (which is part of Google), alongside a range of other smaller providers. Spotify has the largest number of monthly active users by some distance, as shown in the graph below. Music streaming services are popular with consumers and have grown rapidly – between 2019 and 2021 the number of monthly active users of music streaming services increased from 32 million to 39 million.

Despite the strong presence of large, well-known firms in the market, and the number of active users increasing, music streaming services are not making sustained, excess profits: indeed, our analysis has shown that many services have low or negative operating margins.

Share of UK Monthly Active Users by music streaming service in December 2021, excluding YouTube’s UUC platform

Alt text: Bar chart showing the percentage share of UK Monthly Active Users by music streaming service in December 2021, excluding YouTube’s UUC platform. It shows that Spotify has the largest share of Monthly Active Users [50-60]%, Amazon has [20-30]%, Apple [10-20]%, SoundCloud [5-10%]. YouTube Music, Deezer and Tidal each have [0-5]%.

Source: CMA analysis of data from music streaming services.

Notes: This pie chart is for illustrative purposes only. Monthly Active User shares only account for Spotify, YouTube Music, Apple, Amazon, Deezer, Soundcloud and Tidal which have a combined streaming share of over 99% according to CMA analysis of data provided by Official Charts. YouTube Music users include YouTube Music premium Monthly Active Viewers and YouTube Music ad-funded Daily Active Viewers, meaning this figure will provide an underestimation of YouTube Music’s actual users. These figures are provided in a 5% range where the figure is below 10%, and a 10% range where the figure is between 10% and 100%. The midpoints of the ranges have been used to provide an illustration of relative size in the market. Where the sum of these midpoints does not equal 100%, we have scaled the pie chart so that the area segments represent the share of the sum of the midpoints.

We have heard consistently that consumers demand access to a full catalogue of music. The result is that the main music streaming services effectively offer the same music content to consumers. Competition between the services, therefore, anchors around offering the best experience to consumers through good design, personalised playlists, and high-quality audio content, as well as through pricing plans. These services also now compete with one another by offering non-music content, such as podcasts.

For consumers, the monthly price of music streaming services is either free (ad-funded) or is falling in real terms as the price of individual subscriptions have remained stable and not kept pace with inflation. Most services offer a range of price plans, including family and student plans, as well as free ad-funded tiers. Streaming services are now also frequently bundled with other services, such as mobile phone subscriptions, and accessed via a range of devices, including smart speakers.

In a market that is expanding, music streaming services mainly compete for new consumers, rather than encouraging existing customers to switch to their streaming services. However, music streaming services with ad-funded plans do actively seek to get customers to upgrade to a paid-for service.

Switching between music streaming services can be challenging and consumers may be concerned that they will lose access to their favourite playlists if they switch. There are some nascent music data portability services that support switching, but demand for them is currently low. Whilst this is to be expected in a growing market and is not necessarily a dynamic that causes immediate concern, as the market reaches maturity it would be concerning if we did not see more vigorous competition between streaming services and enhanced efforts to make it seamless for consumers to switch and port their playlists or musical preferences.

Whilst the market is delivering good outcomes for consumers now, it is imperative for a sustainable and vibrant market that services can effectively compete with one another, and we could have concerns in future if we saw a reduction in competition.

The legal arrangements between major labels and music streaming services are complex

Like many industries which distribute intellectual property on behalf of others, music streaming services must negotiate with labels and publishers to obtain licences to stream music content and agree suitable financial terms.

A major label relies on music streaming services to distribute its music, and a streaming service cannot meet consumers’ needs without access to the large catalogue of each major record label. As listeners and music streaming services see the majors’ content as complementary rather than substitutable, the extent of competition between majors to supply music streaming services appears limited. Instead, competition between majors appears to be focused more on signing upcoming and proven talent and ensuring that their content is not marginalised on music streaming services.

The contracts between major labels and music streaming services are vital in ensuring that music can be streamed and are inevitably long and complex. Our analysis of these contracts uncovered several non-discrimination clauses such as those which prevent the music streaming service from favouring music content based on price, for example, by giving more prominence to music simply because it is cheaper for the service. We also found a number of Most Favoured Nation (MFN) clauses in contracts covering a range of provisions, including the setting of payment and marketing terms. Subject to their scope, MFN clauses mean the relevant music streaming service cannot offer another record company better terms without also offering those better terms to the major who benefits from the MFN clause. We note that the clauses identified do not relate to the price (or other terms) offered by music streaming services to the end consumer. Accordingly, they are ‘wholesale’ MFNs and can be distinguished from ‘retail’ MFNs which are more likely to raise serious competition concerns. Nonetheless, these clauses might still weaken competition. For example, the non-discrimination clauses and MFNs on marketing terms may restrict music companies from offering a music streaming service better financial terms in return for greater marketing support and could therefore weaken competition in relation to price and marketing.

To introduce innovations or changes to services, the music streaming services typically need to agree with the majors to amend existing contracts, which we heard can be a long process which may slow the pace of innovation. Innovation is intrinsic to a healthy, competitive market and we therefore take seriously any suggestion that innovation has been hindered.

We found examples of substantial innovation by music streaming services, both in terms of the product itself, such as the introduction of high-quality audio, and in the price plans available. But we were also given a few examples of innovations that were slow to market because of the complex negotiations needed to secure licensing agreements. There is a risk that contractual restrictions may contribute to the slower development of such innovations than might otherwise be expected or, potentially, preclude innovation altogether.

While potential competition concerns have been raised with us about the effect of agreements between the majors and music streaming services, it is not clear that any improvement to competition from changing the agreements would be more than marginal. The price MFNs do not prevent the record companies from lowering the price charged for their content, and we are not persuaded, for example, that the agreements are preventing significant competition between record companies on price in return for greater marketing support (that is, a record company agreeing to a lower licensing rate in return for more marketing of its repertoire from a music streaming service). Even without clauses that restrict this type of competition, the majors could continue to use the importance of their content to a music streaming service to secure both high licensing rates and significant marketing support. Further, it is not clear that in the absence of these clauses there would be vigorous competition to promote certain cheaper content given the current business model for music streaming and the need to ensure consumers are presented with music that reflects their interests and preferences.

We are also not persuaded that changing the contractual clauses would significantly increase innovation as music streaming services would still need to agree with multiple rightsholders on what financial terms they can use their content in new and innovative ways. It is these complex negotiations that appear to be the main barrier to even greater innovation, but these negotiations appear to be an inherent part of the licensing process – with the financial terms negotiated depending on the features agreed.

The evidence is mixed on the impact of UUC platforms on the market

UUC platforms allow consumers to access content uploaded by consumers or artists and labels for free (but often with ads), in some cases coupled with other content such as music videos.

UUC platforms differ from music streaming services because any user can upload content, which may include copyrighted material which they may or may not have permission to share. Often this content can appear on these platforms before a licence has been agreed with rightsholders. UUC platforms have some protection in law through a ‘safe harbour’ provision which limits the liability they have for hosting illegal content uploaded by users in some circumstances. However, once they become aware that content is available without permission from rightsholders, they must remove it or, as is more often the case, allow the rightsholder to grant permission and monetise the content.

We have heard conflicting accounts of the impact of the ‘safe harbour ’ provision. While a minority of stakeholders were relatively sanguine about the impact of ‘safe harbour’ protections available to UUC platforms such as YouTube (some labels, in fact, considered YouTube to be a partner), many artists and record companies expressed concerns that safe harbour protections are depressing music streaming revenues. The concerns raised were that removing content from UUC platforms is an onerous and ineffective process, and that this gives UUC platforms an unfair advantage in negotiations which results in music companies securing a worse deal from UUC platforms compared to music streaming services.

The evidence we have gathered so far has focused on YouTube. It appears to pay a broadly similar amount per stream to rightsholders compared to the ad-funded tiers of other music streaming services. However, YouTube may pay out a lower percentage of its ad revenues to rightsholders than other music streaming services, so there may be a ‘value gap’ on this basis. Given that revenues from YouTube itself account for [10-20]% of music streaming revenues in the UK, any ‘value gap’ would need to be substantial for it to have a material impact on the total UK revenues for rightsholders, including artists.

We plan to collect more evidence to test our initial findings and estimate the ‘value gap’ between what UUC music streaming platforms and music streaming services pay to rightsholders. We will share our findings with government and the IPO to help inform their wider work in this area.

The market continues to evolve

The music streaming market is changing rapidly, and further technological advances in the years to come may spark further changes to the way we listen to music. So far, our analysis indicates that the market is on balance delivering good outcomes for consumers. However, we could have concerns in future if aspects of the market changed in ways that harmed consumers’ interests. For example, factors that may give rise to concerns could include:

-

if the major labels or music streaming services began to make sustained and substantial excess profits

-

if future mergers or acquisitions could affect the bargaining power of either music companies or music streaming services, which may in turn lead to worse outcomes for consumers with the CMA likely to pay particularly close attention to any such merger activity and to investigate whether it could lead to a substantial lessening of competition

-

shifts in the way consumers access streaming services that influence their listening behaviour, for example if there is continued growth in the use of smart speakers, and whether this could exacerbate barriers to expansion of streaming services that do not have their own smart speaker ecosystem

-

whether playlists or recommendations will increasingly be generated using algorithms which may direct consumers to listen to a certain type of content, which could cause concern for consumers, artists, and music companies, if that is not done in a fair and transparent way

-

how difficult it is to switch between music streaming services and whether this limits the strength of competition between those services when the market is no longer growing

-

if the level of innovation on the part of streaming services were to decrease; or if innovations that would benefit consumers were to be prohibited by music companies; or if consumers were to be disadvantaged in other ways, including through higher prices

Next steps

We note and welcome the work of the Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport (DCMS), IPO and the Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation (CDEI) and will continue to engage with them for the remainder of the study and share our emerging thinking with them to help inform their work.

In light of our initial findings, we are consulting on our proposal not to make an MIR at the end of the market study. We are also seeking views on the evidence and emerging thinking set out in our update paper. We welcome responses by Friday 19 August 2022.