Francis Maude Oakeshott Memorial Lecture 2014

Francis Maude delivered the 2014 Robert Oakeshott Memorial Lecture on employee ownership and the future of public services.

View full coverage of the minister’s speech on Storify.

Introduction

It’s a great privilege and a pleasure to be invited to deliver this lecture today (25 March 2014) and to be a guest of the Employee Ownership Association and really a genuine honour to deliver the 2014 Robert Oakeshott Memorial Lecture.

It’s great to see representatives from John Lewis, Arup, Gripple, and some of the other amazing private sector success stories here today.

It’s also a pleasure to be at the ICAEW, itself a mutual albeit a membership mutual rather than a staff one. But a great deal of symmetry.

Robert Oakeshott lived through one of the most polarised eras in political history, yet his own place in that order was never a fixed one. His party political affiliations were broadly with the centre-left but he wrote widely, and his writings found expression across the pages of the Spectator, the Economist and the Financial Times.

Independent-minded, he was a man of very strong beliefs. Today his name has become synonymous with this cause above all others — the cause of employee ownership.

Historically, employee ownership has never really had a fixed ideological abode: it was often shunned by the left because of their dogmatic commitment to state ownership; down-played by the right in favour of what some saw as classic red-blooded capitalism.

I was remembering just last week when reading Tony Benn’s obituaries how in the 1970s he tried to save three companies by turning them into workers’ cooperatives, notably the Triumph motorcycle works at Meriden. It was an experiment really in syndicalist industrial reorganisation; and the failure of those ventures I think set back the cause of employee ownership and cooperatives by some years.

Public sector productivity

So how does all of this bear on the reform of public services? In 2010 when the coalition government was formed we faced a public service crisis. We faced the biggest budget deficit in the developed world; we faced rising public expectations relating to the quality of services; and we faced a stagnant economy.

Between 1997 and 2010, according to the Office for National Statistics, productivity in the public sector flat-lined. Yet in the private services sector 0151 the nearest equivalent — over the same period productivity rose by nearly 30%. Even a back of the envelope analysis suggests that if productivity had risen by the same amount in the public sector, the annual deficit could have been at least a quarter smaller — probably much more — a cut of around £50 billion; or the economy larger by a minimum of £2,000 for every household. However you calculate it, the absolutely inescapable conclusion is that our economic and fiscal position would have been radically different.

So how do we drive up productivity in the public sector? There have been plenty over the years who didn’t believe you could. As a Treasury Minister in the early 1990s, I was charged with developing the Citizen’s Charter, an early programme concerned with the systematic improvement of public services. I faced what felt like a tacit conspiracy of defeatism. The Treasury struggled with the idea that services could be improved without departments constantly demanding more money. And departments themselves, faced with demands for better quality, entirely predictably confirmed the Treasury’s gloomy prognosis by — yes — demanding more money.

Absent from both sides was any recognition that productivity could be improved; that more could be achieved for the same amount; that the same could be achieved for less money; least of all the proposition that we are now amply proving on a monthly basis: that you can deliver more for less. This was the defeatist consensus that has held back public services for too long.

That approach reached its nadir in the last decade. The NHS budget more than doubled, but productivity if anything deteriorated. The apparent age of plenty seemed to have relieved the public sector of the need to be creative. And then suddenly one morning there was no money. As sir Ernest Rutherford famously is alleged to have said:

We’ve run out of money. Now we must think”.

Public service reform — 5 principles

Our thinking led us to propose public service reform which has followed 5 principles.

- The first of those principles is openness, because transparency sharpens accountability, improves choice for the public, and it raises standards. So first, openness.

- Second, digital by default. If a service can be delivered online, then it should only be delivered online because as well as being an order of magnitude cheaper — 30 times less than by post and 50 times less expensive than face to face — services delivered online can be faster, simpler and more convenient for the public to use. So second principle is digital by default.

- Third, a properly innovative culture, so public servants have permission to try sensible new ideas, moving away from the risk aversion that has tended to hold back progress.

- Fourth, tight control from the centre over common activities — like property, IT and procurement — because it reduces costs and encourages collaborative working. These tight central controls account for two thirds of the £10 billion we saved for the taxpayer just last year in central government spending alone.

- The fifth principle is loose control over operations, which is where employee ownership steps in. The people who know best how to deliver public services best aren’t the politicians in Westminster or the bureaucrats in Whitehall and in town halls, but the professionals working on the frontline. Tight control over the centre must be matched by much looser control over operations.

Opening up public services

For too long, delivery of public services has been shackled by a top-down, Whitehall-knows-best attitude. Public sector workers were left feeling alienated: dispossessed from effective control over their ability to shape the services they had responsibility for delivering.

Too often there seemed to be a binary choice: either the public sector as a bureaucratic in-house monopoly provider; or on the other hand, full-blown red-blooded commercial privatisation or outsourcing.

Happily, that’s changed and there are now alternatives. Social enterprises. Joint ventures. Voluntary and charitable organisations. And, of course, public service mutuals.

And it’s this last — public service mutuals — that is the fastest growing alternative, which is arousing most interest among governments abroad and which will I believe will increasingly be the way of the future.

Creating a new sector

Why? Because creating a mutual releases creative energy and entrepreneurialism. And that’s the problem many critics have with this programme. They either don’t believe entrepreneurs exist in the public sector. That it’s solely the domain of stuffy bureaucrats. Or they don’t think entrepreneurialism should be allowed to mix with the public service ethos, lest it contaminates the purity of this ethos. Both I believe are wrong. There are loads of latent entrepreneurs in the public sector. They may not think of themselves as entrepreneurs, but they have all of that spirit of enterprise, the willingness to back their ideas, and invest their energy and creativity to make things happen.

It doesn’t mean they all want to be Branson-type millionaires and billionaires. In most spinouts the staff themselves have chosen that the entity should be a not-for-profit company or organisation. They didn’t need to make that choice — they would have had the opportunity to make it a for-profit organisation — but for the most part that’s the choice they made.

Yes you can get improved productivity through conventional outsourcing. That will often be the right option to take. But rarely in my experience does it deliver the almost overnight improvement that mutualisation can stimulate.

The last government started down the path of mutualisation. But their approach was in my view and that of others, too top-down, too prescriptive and bureaucratic; and resulted in no more than a handful of new mutuals.

I decided against this approach. And I want to do something at this stage that ministers too rarely do which is to pay a tribute to the civil servants who worked with me on this programme during this period led by Rannia Leontaridi. This is a team of officials who have been creative, dedicated, incredibly hard working, incredibly effective in making things happen. So I’d like to say a very big thank you to you Rannia and all of your team who have supported me during this programme. So we decided against the top-down approach. So there was no White Paper; no all-encompassing strategy; no big bang media launch. It was what I know think of as the JFDI school of government — the just do it school of government. We didn’t start with the theory and move on to the practice. We did it the other way round. We decided we’d find a hundred flowers and build a hothouse around them so they can bloom and grow.

So the first thing was to identify groups of workers who wanted to spin out from the public sector. As Pathfinders, we gave intensive support to these organisations, who in return shared their experiences with us and with others. Many of these Pathfinders are now among the country’s best performing mutuals.

Next, we made £10 million available through our mutual support programme. It’s not a lot of money — I know that. But we’ve made it go a really long way. The funding isn’t allocated directly. Instead it’s used to build the capability of these new businesses — as that’s what they are — through professional expertise and advice. That’s the way the government can negotiate the best deal and, over time, we’ve built up a valuable set of tools and templates which upcoming spinouts can access and draw upon for free.

And there’s no “one size fits all” approach, no one size fits all format. Some mutuals are conventional companies; some are companies limited by guarantee; some are community interest companies; some choose to be charities. Some have 100% employee ownership; but to qualify there must be no less than 25% employee ownership so that staff can exercise at least negative control over the entity. So there’s a whole spectrum of different models available, and each group must select the right course for their particular horse. Each spinout is a journey for and by its own staff. They’re the ones in the driving seat, leading the change.

Progress so far

And our approach is working.

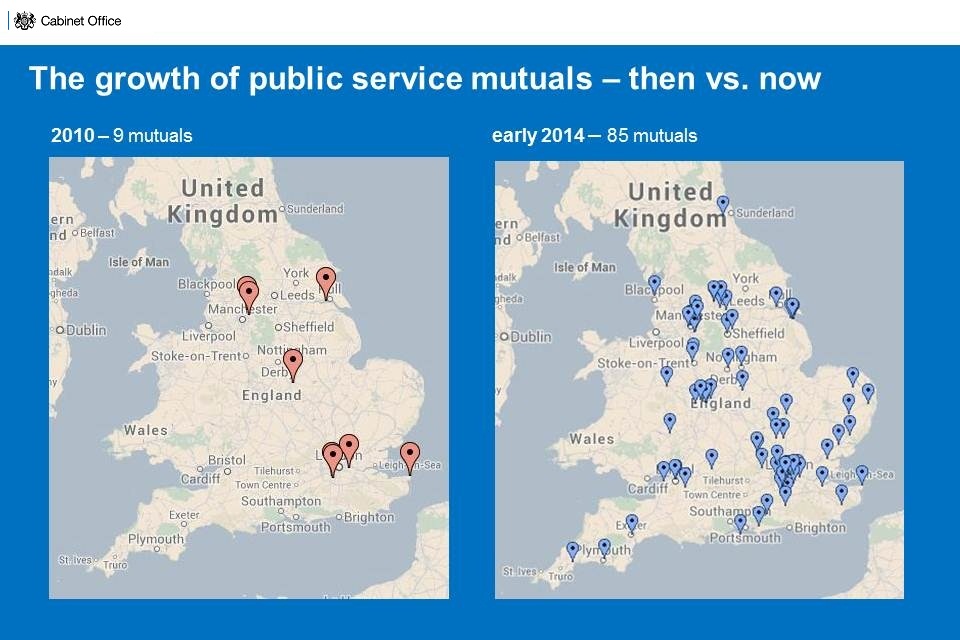

4 years after the last general election, the number of mutuals has increased tenfold to nearly 100. Between them they employ over 35,000 people, delivering around £1.5 billion worth of services. They’re in sectors ranging from libraries and elderly social care to mental health services and school support. They range in size from a handful of staff to upwards of 2000 staff.

Neither is this confined to any one region — it’s certainly not a London niche – it’s a national success story. The map of mutuals shows them spread across Britain. The results are spectacular. Waste and costs down. Staff satisfaction up. Absenteeism — a key test or morale and productivity — is falling and falling sharply. Business growing.

Staff engagement surveys bear out the simple truth that service improves and productivity rises when the staff have a stake; when they feel they belong; and that their individual voice and actions count.

Our latest data shows that after an organisation spins out as a mutual absenteeism falls by 20%; staff turnover falls by 16%. Take City Healthcare Partnership based in Hull as an example. 91% of staff said they now feel trusted to do their jobs — and this level of empowerment has had a knock-on effect in the quality of care they give. Since they left the NHS in 2010, there has been a 14% increase in patients who’ve rated their care and support as excellent, and 92% say they would recommend the service to family and friends.

No wonder City Healthcare came 46th in the Times 2014 top 100 not for profit companies to work for.

At SEQOL in Swindon, a groundbreaking mutual formed by integrating in one entity intermediate healthcare activities from the PCT with some social care activity from the council, staff proudly showed me the stockroom, where a nurse had painstakingly attached stickers with the unit price of each item. “Why did you do that?” I asked the nurse showing me round. “To make us more aware of the cost so we could save money”, was the response. “But why?” I persisted. “You’re a not for profit organisation and none of you will benefit financially from the savings you make”. “No. But every pound we save makes us more competitive. And it’s a pound we can put straight back into better patient care”.

And that’s the point. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with better financial reward for public servants. But it’s not the biggest driver of better productivity. It’s the satisfaction people get from putting their ideas into action, and seeing swift results. It’s the sense of pride that it’s their organisation that is delivering the service. That they can make improvements quickly, taking responsibility for making things happen, without new ideas getting bogged down in bureaucratic treacle. Just looking at the Baxendale Awards for Employee Owned Businesses this year, you can see the spinouts dominating the innovation category. So in a mutual, public servants can give effect to their public service ethos with immediate and gratifying speed.

Whenever I visit a mutual — which I do a lot, it’s a drug, it’s addictive — I always ask the same question of staff: “Would you go back to work for the council/health authority/ministry?”

The answer is always “No”. “Why not?” “Because in a mutual we can do things.”

That’s the essence of it. People can see how things can be done better and do it. They can give effect and take responsibility and pride for making things happen. People typically say they are working harder than they were but they are enjoying it more, it’s more rewarding, more fulfilling. That’s why I think the public service mutual is the way of the future.

Growth

Of course, the public service ethos remains front and centre. But it doesn’t have to be at the expense of strong commercial instinct.

Spinouts are winning new business — and winning new business fast. A study from Boston Consulting Group projects an average increase in revenues of 10% this year.

MyCSP, which is responsible for administering the Civil Service Pension Scheme, was the first mutual joint venture to spin out from central government. Under its contract the cost of the service to the taxpayer will halve over 8 years. The private sector partner has taken on the transformation and IT costs that would otherwise have fallen to the Exchequer. Under its innovative equity structure, the government retains a 35% stake. The staff, with a 25% stake, all received a first year dividend of nearly £700. And in its first year of operation it gained 47 new clients. This is a growth business.

Social AdVentures in Salford saw a growth in revenues last year of no less than 262%.

3BM in London increased their business by over 25% in their first year as a mutual.

Since spinning out in July 2011 — in the middle of the economic downturn — Allied Health Professionals in Suffolk has increased its number of staff from 63 to around 100; its turnover from just over £2 million to £3 million — all on the back of winning new contracts.

And in Norfolk, East Coast Community Healthcare’s first year profit was 40% ahead of plans.

The point is that each of these new mutuals represents a new and dynamic enterprise in the market economy. They are all incentivised one way or another to improve and grow. They all strengthen the market for their services and they make the market deeper, wider and more competitive. And as we have seen all too clearly in the last year, public service commissioners had become too dependent in too many areas on too limited a range of suppliers. Every new mutual helps to remedy that deficiency to improve the depth and dynamism of the market.

Argument

So — cutting costs; improving quality; supporting economic growth and jobs: what’s not to like about all that?

I had a really interesting experience recently when successfully negotiating in the European Parliament some much needed changes to EU public procurement rules. We wanted to have a provision that would shield future new public service mutuals from the immediate full panoply of EU regulations while they established themselves as businesses. We had brilliant support from British Conservative and Liberal MEPs. But beyond them? Well, the socialists thought that it was promoting privatisation by the back door. And some on the centre-right thought it was a scandalous erosion of the pure milk of the competitive free market.

Well let’s examine both contentions. Is mutualisation equivalent to privatisation? Technically yes. Mutuals are spinouts from the public sector into the private or social sectors so they get classified as non-public sector. It’s certainly not privatisation by the back door though. It’s as open a process as you could want.

On the other hand does mutualisation by negotiation frustrate competition? Well actually not at all. It promotes it. It opens it up a broader hybrid economy with a wider range of suppliers — there’s a place for mutual spinouts, joint ventures and charities and voluntary organisations, alongside private companies and the public sector. So it’s just worth asking ourselves why is such a small proportion of public service delivered by suppliers outside the public sector? Because I think part of it is conventional outsourcing and privatisation is fraught with political and industrial relations risk. It can look ideological and dogmatic, and can arouse the hostility of the staff. It makes managers anxious because of the fear that the contract will be overpriced leading to excess profits and uncomfortable hearings at the Public Accounts Committee.

But mutualisation can square all these circles. If it is driven by the staff and is a not-for-profit then where’s the problem? And if it’s for profit then why not keep a stake for the state? Then the taxpayer benefits along with the staff and managers. And often the alternative to a mutual joint venture is a straight outsourcing. And I don’t come across many public servants who, if their operation is going to move out of the public sector, wouldn’t prefer themselves to have a stake and some control over the new entity.

So for the staff it can feel like a lower risk alternative to straight privatisation and for managers a way of harvesting productivity gains without the downside of immediate competition. Because in nearly all situations, a negotiated spinout into a mutual or mutual joint venture must be followed after a few years by an unfettered competition, where the mutual will have the advantage of a track record and incumbent advantage but will staff to go up against the competition.

Next steps

But while we have come a long way since 2010, we’ve only reached the end of the introductory chapter of this story. For many years to come the state is going to be facing, here and across the world, the same combination of tight budgets, rising expectations and challenging economic circumstances.

We’re going to continue to be expected to deliver more for less; so the transformation can never cease — spreading deeper and wider, further and faster. Public service mutuals should be front and centre of that transformation. So we now need to move on the next chapter in this story.

First, I want to remove the blocks that obstruct motivated staff from spinning out from public sector control.

I can announce today plans to establish a peer review scheme to support staff and local authorities interested and involved in developing mutuals. Working with the Local Government Association, we’re looking to establish a voluntary programme that will offer best practice advice and examine perceived barriers to spinning out.

And our new Commissioning Academy will continue to build among commissioners across the public sector knowledge and confidence in how to support and negotiate new spinouts.

Second, I want to encourage even more spinouts in those areas where significant numbers of mutuals have already been created, such as healthcare.

Next month, following his review of staff engagement in the NHS, Chris Ham will provide a set of recommendations to government. Chris’ review has looked at how to give staff a stronger role in their organisations, including through mutual models. This included looking at Circle’s incredibly successful strategy for empowering and engaging staff at Hinchingbrooke NHS Trust and supporting frontline staff in delivering service change.

And we’re also working with the Department of Health to explore options for increasing staff control across the NHS, including expanding the Right to Provide.

Third, we’re going to focus our efforts on sectors with the greatest potential. I have spoken about the potential in youth services and adult social care where there are huge opportunities for mutualisation. We are also working to expand the offer in children’s services and in acute trusts. I have ensured that the current probation reforms have mutuals as a serious delivery option. We’ve even had expressions of interest from fire brigades about mutualising fire services in 1 or 2 areas.

Fourth, because what we’re seeing here is the creation of a whole new sector of organisations, I want to ensure that their progress and successes are recorded and underpinned by quality data which is freely available.

So far we’ve done much of the research in-house, in keeping with the kind of start-up nature of this programme. But as with any successful policy, maturity is marked by the state taking a step back.

I am pleased to announce that Cabinet Office we’re working with the Employee Ownership Association to set up a networked centre that brings together all the data on spinouts into one place, allowing everyone to see how they’re performing and what they’re achieving. That’s the next chapter in this story.

Beyond the public sector

The potential for growth is echoed in the private sector experience too. The employee owned sector has been one of the quiet success stories of the British economy in the last 20 years. Companies which are employee owned, or which have large and significant employee ownership stakes, now account for over £25 billion in total annual turnover. And they’re helping to lead the economic recovery, by growing at a rate 50% higher than the economy at large.

So support for employee ownership across both sectors has been and will remain a priority for this government and a core part of our long-term economic plan, a point reinforced by the Chancellor in last week’s Budget, which confirmed 3 new tax reliefs to encourage and promote employee ownership; I’m sure you all look forward to seeing more detail on these in the Finance Bill being published I think later this week. This had a nostalgic resonance for me. I recall as Financial Secretary to the Treasury working on the tax measures to support employee ownership that appeared in the 1991 Budget! This will always, I suspect, be a work in progress.

Conclusion

So, to conclude, 35 years on from Robert Oakeshott creating the Employee Ownership Association, now is the time to put employee ownership right at the heart of our public services.

Shifting power away from the centre and diversifying the range of public service providers is a historic opportunity to redesign how public services are delivered — not just to reduce costs, but to improve service, increase staff morale and stimulate growth.

And that’s a winning combination.