PM and Deputy PM speech on emergency security legislation

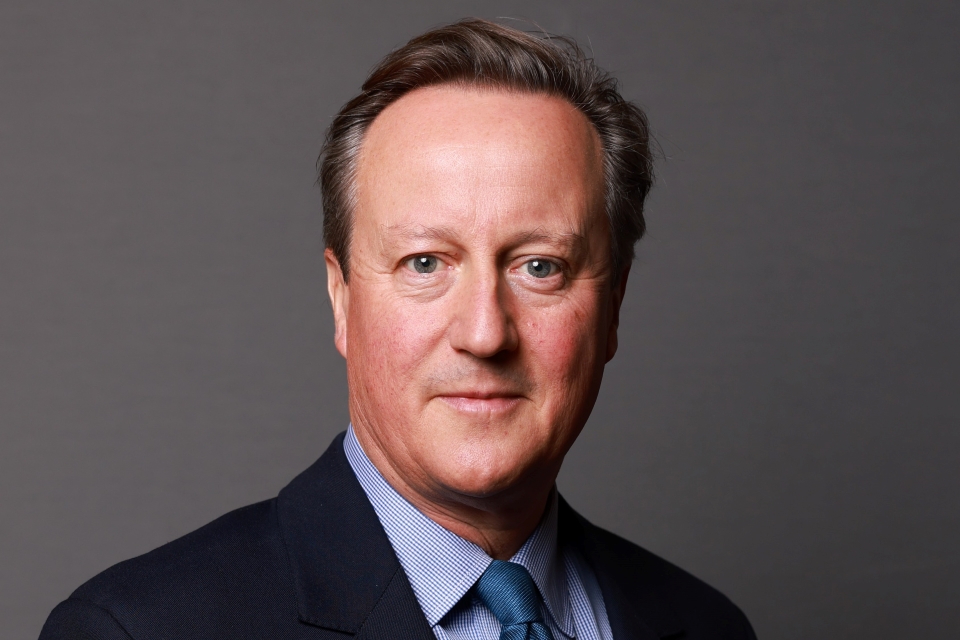

David Cameron and Nick Clegg discussed new emergency legislation on access to telecommunications data at a press conference at Downing Street.

Prime Minister

Good morning. As Prime Minister, my first duty is to protect our national security, and to act quickly when that security is compromised.

In recent weeks there have been 2 developments that require urgent action. First, the European Court of Justice has struck down legislation that enables telephone and internet companies to hold data for security purposes. This means that unless we act now, companies will no longer retain the data about who contacted whom, where and when, and we would no longer be able to use this information to bring criminals to justice, and to keep our country safe.

Now, let me be clear. I am not talking about the content of those communications, just the fact that those communications took place, the so called ‘communications data’: information about who contacted whom, when and where. This is at the heart of our entire criminal justice system. It is used in 95% of all serious organised crime cases handled by the crown prosecution service. It has been used in every major Security Service counter terrorism investigation over the past decade, and it’s the foundation for prosecutions of paedophiles, drug dealers and fraudsters. For example, without mobile phone call logs the killers of Rhys Jones and the men who groomed young girls in Rochdale would not have been convicted.

Now, the second, entirely separate, development concerns the legal framework to underpin those very specific instances where telephone and internet companies work with government to share the actual content of communications. Listening to someone’s phone calls or reading their emails is an extremely serious thing to do. So let’s be absolutely clear about the very strict circumstances under which this happens, and the clear framework of accountability that we have in our country.

The case for a warrant has to be made based on threats to our national security, or serious criminal activity. The request – the request to access data has to be necessary and proportionate with that risk. Warrants have to be signed off personally by a Secretary of State; they are reviewed by the independent Commissioner, who is a senior judge. And of course all the work of our security services is overseen by Parliament’s newly strengthened Intelligence and Security Committee (ISC).

Sometimes in the dangerous world in which we live we need our security services to listen to someone’s phone or read their emails to identify and disrupt a terrorist plot. As Prime Minister, I know of examples where doing this has stopped a terrorist attack. We rely on the assistance of telephone and internet companies.

Some companies are now questioning whether there’s a legal basis for them to share the content of data with government when their company is not based in the United Kingdom. We’ve always maintained that the law requires this wherever a company is based, but there is now a real risk that legal uncertainty will reduce companies’ willingness to comply with UK law even where they would wish to support us in the fight against terror, child abuse or other serious crimes.

Some companies are already saying they can no longer work with us unless UK law is clarified immediately. So failure to act now would fundamentally undermine our capability to counter a range of threats to the safety of our citizens, and I will not stand by and let that happen. So we’re going to introduce emergency legislation to preserve these 2 vital capabilities:

- first, the capability for telephone and internet companies in the UK to retain data on who contacted whom, when and where, essentials to so many prosecutions at the heart of our criminal justice system

- second, the capability for such companies who offer services to UK customers to assist in specific UK national security or criminal investigations, regardless of where in the world these companies are based

These capabilities can only be restored through legislation, and this must be done quickly, before companies stop retaining the data, and before companies stop sharing the vital information that we need. So Parliament will consider this legislation before the summer break. I’m determined to proceed on a cross party basis. The Home Secretary will be making a statement to the House of Commons later this morning, and there’ll be a full debate on the floor of the House next week.

Read a statement made by the Home Secretary on communications data and interception in the House of Commons.

Of course, at the same time as acting to restore these capabilities it is vital that we always ensure we get the right balance between protecting our people and preserving the right to privacy. So in restoring these powers, I’m building on the existing measures to introduce more safeguards and transparency over how these powers are used. And while we have to take these measures to restore existing capabilities immediately, I want this to be the beginning of a wider, more substantive debate in the next Parliament about the powers we need to protect our people in an era when technology continues to evolve.

Let me briefly take each of these points in turn. First, on additional safeguards, when it comes to that communications data it’s not just government that needs this information: for example, it’s local authorities who use it to protect the vulnerable; the ambulance service who use it to trace an emergency call when the mobile calling them loses reception or gets cut off.

But there are a number of bodies who have, for many years, had access to this data without the same obvious need, and it is time for that to change. So the Deputy Prime Minister and I propose to limit the number of public bodies which are able to make requests to access communications data through legislation in the autumn. As a result, organisations like the Royal Mail, the Charity Commission and the Pensions Regulator are among more than a dozen bodies that will lose access to this data, whilst others will face additional screening before their requests for data are agreed.

Second, to ensure that we strike the right balance between security and privacy, we’ll build on the work of the Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation by creating a new Counter Terrorism, Privacy and Civil Liberties Board to scrutinise government policy and legislation.

Third, a number of overseas companies have asserted that their ability to work with the UK government is being severely constrained by international conflicts of jurisdiction. For example, where they think they have a British law saying that they should share data, and an American law saying that they shouldn’t. So we intend to appoint a senior diplomat to work with America and other countries to address these concerns and ensure that lawful and justified transfer of information across borders takes place to protect our people’s safety and security.

Finally, we’ll take additional steps to improve transparency by publishing an annual transparency report, which will set out in greater detail how many warrants are authorised each year, and for what purpose, and with what effect. The steps we’re taking today are not about new obligations for phone and internet companies, nor any new intrusions on civil liberties. They are about restoring and maintaining capabilities that are vital to our national security.

As you know, I proposed a new Bill on Communications Data in the last Parliamentary session. That Bill would have extended our capabilities to new internet technology, and I want to be clear with you: none of those measures are being introduced here today. This is merely about plugging holes in our existing legislation to maintain these vital capabilities.

But I do believe we should have a debate about our long term approach to maintaining vital security capabilities as technology develops. So the Deputy Prime Minister and I, with the support of the Leader of the Opposition, have invited David Anderson to lead a comprehensive review of the capabilities our security and intelligence agencies need, and the safeguards that govern their access to private communications.

We will then establish a joint Parliamentary committee to review the legislation and to report after the election so it can inform that debate. And we are proposing a termination clause on the emergency legislation that you can see today that will preserve our powers up until the end of 2016, and only up until then, and that will force a proper debate in the next Parliament.

Now, we face real and credible threats to our security from serious organised crime, from the activity of paedophiles, from the collapse of Syria, the growth of ISIS in Iraq and Al Shabaab in East Africa. And I’m simply not prepared to be a Prime Minister who has to address the people after a terrorist incident and explain that I could have done more to prevent it.

Our police and our security services do an often unsung and truly incredible job, regularly putting themselves in grave danger to protect us from these threats. As Prime Minister I would always ensure that they have the tools to do the job to keep the country safe today and in the years to come.

Thank you. The Deputy Prime Minister is now going to speak about this issue as well.

Deputy Prime Minister

Thank you.

As a Liberal Democrat I believe that successive governments have neglected civil liberties as they claimed to pursue greater security. But I will not stand idly by when there is a real risk that we will suddenly be deprived of the legitimate means by which we keep people safe. Liberty and security must go hand in hand; we can’t enjoy our freedom if we are unable to keep ourselves safe.

So I wouldn’t be standing here today if I didn’t believe there is an urgent challenge facing us. No government embarks on emergency legislation lightly, but I have been persuaded of the need to act, and to act fast. As the Prime Minister has set out, we face the very stark prospect that powers we’ve taken for granted in the past will no longer be available to us in the coming weeks.

Now, much of this might sound like a lot of technical, legal issues, but communications data and lawful intercept are now amongst the most useful tools available to us to prevent violence and bloodshed on Britain’s streets. There are multiple plots that we rely on our police and agencies to stop. You will remember the plot to detonate liquid explosives on multiple transatlantic flights in 2006 and there are lots of other examples.

Vital to the work of the police and the agencies is lawful intercept, which allows them to look, under warrant, at specific communications between individuals, who may be planning plots of this time, and without retained communications data, we wouldn’t, for example, be able to piece together the web of relationships between members of the organised crime gangs responsible for trafficking drugs and vulnerable children and adults into our country.

I’d like to make 3 further points:

- first, and crucially, this bill has nothing to do with the so called ‘Snooper’s Charter’. That was a Home Office proposal to store every website you’ve ever visited for a whole year. I blocked that last year and I’ve blocked every further attempt to bring it back.

- second, as I touched on earlier, this is about maintaining existing capabilities, not creating new powers. The legislation will restore the data retention powers we had before, but amend the law to do it in a more proportionate way. And it will help companies which currently provide assistance with UK intercept warrants to continue to do so

- third, I have only agreed to this emergency legislation because we can use it to kick-start a proper debate about freedom and security in the internet age. A debate the Liberal Democrats have been calling for, for a long time. In the post Snowdon age, people are, rightly, demanding to know more about what the state does on our behalf. There are fundamental questions to be asked about the scope of existing powers; about whether the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (RIPA) has kept pace with technology; about how nation states grapple with a global internet; and about how we continue to protect security, privacy and liberties while safeguarding our security.

We can’t answer those big questions on the hoof, and that is why I’ve insisted that the legislation only extends the existing powers for a temporary period. We’ve inserted a termination clause in the Bill that means the legislation falls at the end of 2016, so the next government is forced to look again at these big issues. We’re giving ourselves the time we need to look at all these issues in a considered way.

We will do that in the first instance by asking the independent reviewer of terrorism legislation to carry out a review of our communications data and intercept laws. Then, starting early in the next parliament, all 3 party leaders will commit to a full parliamentary review of RIPA, leading to proposals for an updated and reformed approach in 2016.

This is exactly the approach I’ve been advocating for months, and the reason why I asked the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) to set up their own expert panel back in March. And I’m pleased that the work of RUSI will now be accompanied by other reviews looking at every aspect of these issues.

On the question of the application of the law to foreign service providers, I don’t believe the Bill we’re putting forward today presents the whole solution. There are broader issues around how the authorities in one country access data which is held in different legal jurisdictions. We need to discuss these legal complexities between governments, and that is why we will be appointing a senior former diplomat to lead discussions with the American government and the internet companies to put these issues on a more stable footing through an international agreement.

At the same time, we will introduce new checks and balances to protect privacy and civil liberties for the future. We will establish for the first time, as the Prime Minister has said, a Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board on the American model to ensure that civil liberties are properly considered in the formulation of government policy on counter terrorism.

And finally, we will take practical steps to improve the accountability and transparency of our laws. We will radically cut the number of public bodies who have the right to approach phone and internet companies for your data. I don’t believe, for example, that local councils should unilaterally be able to access your communications data. From now on, councils will need to justify their requests first to a central body, and then a magistrate, and will not be able to approach phone and internet companies directly.

We will also for the first time publish regular transparency reports, listing new details about exactly how many warrants are issued, by whom, and for what purposes. The public will know more about how and why surveillance powers are administered on their behalf than ever behalf.

We have been working on this on a cross party basis, and I want to thank not only the Prime Minister, but also the Leader of the Opposition for his cooperation in achieving a balanced package which restores necessary powers while at the same time taking big new steps to defend our civil liberties.

Prime Minister

Thanks very much. We’ve got some time for questions. We’ll start with Nick Robinson.

Question

Thank you very much indeed. Nick Robinson, BBC News. One on the practicalities and one on the approach, if I may.

How is this different from what some people may regard as state sponsored phone and email hacking in practical terms?

And then, does history not warn us to be very suspicious of politicians who say: “We all agree; there’s an emergency. We have to legislate in haste. Don’t worry your heads; it’s all going to be fine”? Shouldn’t people be rightly suspicious of any politician who says that to them?

Prime Minister

Okay, well let me – let me try the first part first. The government has had the power to do 2 vital things. First of all, to make sure that you can find out who has called whom, when, and where from, in order to test someone’s alibi, in order to solve a serious crime. And as I put it, in 95% of serious crimes, that power has been absolutely vital.

Now, we are not legislating to extend that. We are not legislating to extend it into new areas of technology. We are simply saying that the right of law enforcement agencies to be able to look at that communications data – who called whom, and when – should continue into the future. And if we don’t do anything, the danger is those mobile phone companies and other telephone companies will destroy that data. So this is not new – this is not a new power that the government is giving itself. It is to make sure we can go on solving those vital crimes.

In terms of your question about, you know, ‘Should the public be worried?’ I think the public should be worried if we didn’t act. As Prime Minister, I am standing here and saying very clearly that if we don’t do anything, our ability to solve serious crimes will be radically reduced and our ability to prevent terrorist acts will be radically reduced. I’m not standing here asking for new powers and new capabilities; I’m standing here saying we need to legislate, very rapidly, to keep those capabilities and powers that we have.

The time to debate what more we might need to do, we’ve agreed, is for the future. My own very strong view is that we need to ask ourselves this simple question: do we want, as a country, to leave a means of communication for paedophiles, terrorists, and other serious criminals, to communicate with each other that, in extremis, we cannot intercept?

My own view is, no, we don’t. Governments up to now have always taken the view, whether it is to do with the mail, whether it is to do with fixed telephony, whether it is to do with mobile phones, in extremis, to keep the country safe, there are occasions when you need to be able to intercept those communications.

I believe that as technology develops, we will have, over time, to do more to make sure that they – we don’t give paedophiles, terrorists and criminals another way of communicating that we can’t, in extremis, intercept. But that debate’s for the future. That debate’s not for today. Today is simply about maintaining the existing capabilities that we have, and we have come to the conclusion that the right thing to do is legislate – to legislate rapidly. And I think if we explain it as clearly as that, we can take the public with us, particularly given that we are actually adding existing safeguards even before we have that debate about the future.

Deputy Prime Minister

The only thing I would add, in answer to the question: “Is it right for people to be sceptical, to pose questions, to make probing queries when all 3 parties in Westminster say we must act and act fast?” – yes, of course. As an old fashioned liberal, I think it’s incredibly important that people ask anyone in a position of authority about why the powers that are administered on behalf of the public are done in the way that they are, particularly when many of them are wielded in secret.

All I would say is, firstly, as the Prime Minister has said, this is merely maintaining existing capabilities, but, crucially, we have inserted a ‘poison pill’, if you like, into the legislation. That it will fall in December 2016. We are not putting anything permanently on the statute book. What we are doing is recognising an immediate need to shore up existing capabilities.

We are not pretending we have all the answers to all these complex issues in the meantime, and we are admitting that wider debate which we will have to have, and which will need to be decided upon one way or the other early in the next parliament, and there’s a timetable. The next government, the next parliament will have to decide what to do before the end of 2016 because these things will lapse.

So I don’t think there can be a clearer guarantee to the British people, who are acting proportionally and carefully, and thoughtfully, other than the fact that we’re taking the very unusual step of saying that we’re only doing this temporarily. It is a temporary extension, we’re not pretending that we’ve got all the other answers, we’re setting up processes, the review of RIPA, the negotiation, led by a former senior diplomat with the Americans to try to come to a government to government agreement so that we can have more durable and balanced solutions to all these legitimate questions by the end of 2016.

Question

Patrick Wintour, the Guardian. Can I ask the Prime Minister, did you not set your face against the debate about the accountability of the security services and the way in which the Deputy Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition, indeed, the President of the United States, didn’t? And you’d specifically said – and you’ve got the ISC to say this as well – that the warrants were legal. What’s changed on that?

Secondly, what are you actually doing in terms of complying with this ECJ ruling, because you, as far as I can see, are retaining all the powers you currently have. You’re making a point of the fact that you’re not extending them, but you’re retaining them.

And lastly, why are you doing this under emergency powers? It’s perfectly possible that this ruling – ECJ ruling, will not be settled in the UK courts until probably late autumn.

Prime Minister

You have 4 questions there. I’ll do each one in turn. First of all, why is it an emergency? It is an emergency, quite simply, because if we don’t deal with the data retention issue, mobile phone companies could start deleting their records of the comms data of who called whom and when. They could start doing that relatively rapidly, and we’d lose this information that helps the National Crime Agency, it helps the police to solve crimes.

So it is an emergency. It’s also an emergency in terms of interception, because companies have told us that they may start not cooperating with the request, because they don’t think the law is sufficiently clear, so we are satisfied that it is an emergency and we do need to legislate on the basis of an emergency.

On the European Court of Justice, what the European Court of Justice did was actually strike down the European Data Retention Directive. What we had chosen to do as a country was to have secondary legislation under that directive rather than primary legislation. So countries like Denmark that have their own primary legislation are fine; they don’t need to do anything. But effectively, because the actual directive has been struck down, we are left in a position where we need primary legislation to put beyond doubt the need for those companies to retain that data. Again, we’re not asking them to do anything new; they are being asked to do what they were doing anyway. And it wasn’t our law that was struck down, it was the Data Retention Directive.

In terms of warrants, an argument I would make is that – and I made this argument before, and I make exactly the same argument today – our system for interception, warranted intercepts, is a very, very strong one.

A warrant is put up to the Home Secretary; she has to look at it in detail; she’ll redirect some warrants, she’ll ask for changes to them. She then signs a warrant– no one’s telephone can be listened to until this process is gone through. A warrant has to go up to the Home Secretary, has to be signed by the Home Secretary, this is then overseen by an Interception Commissioner who writes an annual report – and I’d recommend you read Sir Anthony May’s report, it’s a brilliant description of how this system works. The ISC, the Intelligence and Security Committee, then reviews the whole system and the way that our approach works.

And I think that is probably one of the best and most accountable systems anywhere in the world for carrying out what I described in my statement. It’s very difficult but necessary work to keep us safe.

In terms of the debate, I’m all for holding a debate about this issue, but I want to do it in the context of making sure that we are at least maintaining the capabilities that we have. Let’s by all means have a debate about what needs to happen next, but of course as technology advances, terrorists, paedophiles and criminals are finding all sorts of new ways to communicate with each other. And the debate we’re going to have, as well as what are the right civil liberties safeguards which is a good debate to have – we’ve also got to have a debate about do we need new laws and new rules so that we can actually, if necessary, intercept the communications that terrorists, paedophiles and criminals are going to be having using new methods?

To take a really big picture way of explaining this – when we moved from only being able to communicate via the Royal Mail to having telephony, should a government at that stage have said, ‘Well, obviously we can’t either ask companies to retain data about telephone calls nor can we intercept someone’s telephone call even if there’s a terrorist plot taking place.’ I think that would have been a bad decision.

Likewise, I think it would be a bad decision if – as the world goes from fixed telephony to mobile telephony and into new forms of communication, I think it would be a bad decision to say there’s nothing we can do about these new forms of communication. But that’s not a debate for today, that’s a debate for between now and the election, at the election and after the election, but I’m pretty clear about where I stand in that debate. But yes, we must debate both the civil liberties issues and the capabilities issues for the future.

Question

Sam Coates from The Times. People who read the Edward Snowden revelations might be slightly perplexed today because the impression created by those was that the security services do have the ability to go in and examine and hoover up quite a lot of data that’s out there on the internet on Gmail and services such as that.

What would you say to the argument that you’re dealing with the stuff that we see in court, but the question is whether or not the emergency legislation makes any changes to the framework that the security services will operate under – that kind of regime. And secondly, someone in Labour is saying that they asked for changes to the way the Intelligence and Securities Committee operates and that the chair, in future, should be an opposition figure. Is that a recommendation that you’ve accepted?

Prime Minister

Okay. We’ve just changed the way the Intelligence and Securities Committee elects its chairman. It used to always be appointed by the Prime Minister. The House of Commons has just legislated that in future the members of that committee will choose the chairman, and they could choose the chairman from the opposition or from the government. So I don’t favour making this further change, but I’m very happy for it to be debated and discussed.

I think what really matters is that the ISC is fully independent, that it’s capably led, that it’s got all the resources that it needs; but actually Parliament has literally just legislated to change the way that it’s done. Parliament, of course, can take another view and go even further and do something else. Happy for that debate, but I’m not proposing that today.

In terms of Snowden – what we’re proposing today does not change the capabilities that our intelligence services have under the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act. It is just dealing with a specific problem that some companies are questioning - whether there is adequate legal grounds for them to cooperate if they’re no longer based in the UK even though they’re providing services in the UK. So we’re not changing the capabilities or the rules today, but all of that, as I’ve said, is a debate for the future.

Deputy Prime Minister

Shall I – on the first point, this only affects those legal intercept activities, all of which are subject to warrants. And that perhaps suggests that there are more checks and balances in the current system, never mind the traditional checks and balances which might be introduced in the future, that I think have sometimes been portrayed.

On the ISC – the Prime Minister’s quite right, there will be further debate on this. When that further debate happens, I personally believe that – it might be fair, it might be unfair, I don’t know, but there is clearly a need to make sure that the ISC’s independence from the government of the day is – in perception as well as reality – is seen to be very, very clear, and that’s why I’ve become persuaded of the case that it would be, in the future, right that the chair of the ISC automatically comes from the ranks of the opposition party.

But as the Prime Minister said, let’s have that debate; I think in the long run it would do the ISC good to have that clear difference so the chair always comes from the opposition ranks.

Question

Tom Newton Dunn from The Sun. Prime Minister, you say the debate for future powers, more legislation – rather than just by your admission standing still, which is really what you’re doing today, or having to do – is for the future. But by putting forward the Communications Data Bill which you’ve strongly backed Theresa May on doing, you’ve made it very clear that the debate needs to happen now.

So do you accept and will you admit by not going further today – just effectively standing still – you’re already taking risk? And Deputy Prime Minister, you’ve heard the same briefings as the Prime Minister and the Intelligence Services, who really wanted a lot more than they’re getting today. Do you accept that there’s also risk and therefore if that risk unfortunately comes true, you’ll have blood on your hands?

Prime Minister

What I would say, Tom, is – look, today it wouldn’t be appropriate to use emergency legislation to change capabilities for the future. The emergency legislation is right, because we’re facing a potential cliff edge of loss of intelligence, and that would be a bad thing, and so we need to correct that and we need to correct it urgently. There is a debate to be had for the future about how you apply the current system that we’ve got, both of retaining the communications data – the ‘who called whom and when’ bit – and also being able to intercept the content of communications. As we go into a world of 5G and voice over internet and all the new technologies, there’s a debate to be had about how you do that. We had the Comms Data Bill; it was decided in the coalition not to proceed with that. I think this RIPA review that David Anderson and the cross party committee can look at may help to build some more consensus for that.

But I think it is important to try and proceed on the basis of consensus; I don’t want this very difficult and sensitive area to be subject to a whole lot of party political ding dong, I don’t think that would be good for our country, I don’t think it would be good for our security. So let’s have the debate; I hope we can build consensus for taking further action, but today is about shoring up our current system.

Deputy Prime Minister

Of course you need to constantly look at how technology is evolving and ensure that we – where we can and where it’s appropriate, where it’s proportionate – keep up to date with technological developments.

So for instance there’s this obvious issue that IP addresses are not easily traceable to individual people; I think that’s a real issue, and it’s something I’ve always said publically I think we need to address. We need to take further steps to do that. I don’t believe that in a mature liberal democracy – small l, small d, it is right to suggest to legislators and to governments that every single conceivable power that is requested should always be granted. That’s part of the checks and balances of the free society that we live in is that we balance issues to do with security and the powers needed to safeguard security against the long held British proud traditions of liberty, of privacy, and of civil liberties.

And that’s why I came to the judgement that the proposal that every single website that you, Tom, visit – every single one – is stored for a whole year – I didn’t feel that was a proportionate response to the threats that exist. But of course, as we’ve both said, this debate will resurface again and again; we now have a clear timetable by which that debate now needs to be closed and decisions need to be made.

But I balk at the suggestion that governments of all shapes and sizes and all political hues should just always willy nilly grant whatever new power is proposed. Part of the role of parliaments and governments is to strike the right balance, and that’s exactly what we’re seeking to do today.

Question

Rob Hutton from Bloomberg. One quite specific question, when did you settle on the idea that emergency legislation was the solution to this? Because I think the ruling was a couple of months back, and we’re now very close to the end of the Parliamentary term.

And one more general one; the oversight that you’ve described to us of how interception takes place is completely at odds with the oversight that Snowden has described to us. When the Snowden revelations came out, was your response, “Hang on a second” – to go to GCHQ and say, “Hang on a second, this isn’t what you told me was going on”? Or was it to say, “Oh dear, they’ve found out”?

Prime Minister

Okay let me – first of all, why are we having emergency legislation and the timing behind it? We’ve had these 2 problems, as I put it, the comms data problem and the legal intercept problem. Of course with comms data, when we lost the case – or rather when the European Union effectively lost the case in the European Court of Justice, we looked at –- well what are the options? Could we do secondary legislation? Could we correct this in another way? Is there another Bill that we could use?

And we came to the conclusion that the safest legal way to deal with this was primary legislation, and that was added to when – again, the problem of legal intercept, we looked – are there ways we can clarify the law without legislating? Are there ways we can have agreements with other governments to clarify this issue? And again we came to the conclusion, actually, the only safe and secure way is legislation.

There’s an urgency with both of these, because obviously if we lose companies helping with legal intercept, we then lose important capabilities, and obviously if we don’t have companies retaining communications data, we won’t have the information to catch criminals, terrorists and paedophiles, and that data could start to be destroyed quite quickly.

So in both cases the argument came together – and we’ve been discussing this – that actually legislation was necessary before the end of this Parliamentary term. So that has been a discussion we’ve been having over the past few weeks, in order to try to make sure that we have in place – we only do what is necessary to maintain our capabilities, and we do what is right in terms of safeguards, and that’s been a discussion that we’ve had over the last few days, and that’s how the decision’s been reached.

Deputy Prime Minister

You mentioned it earlier, but it’s quite important to remember that the European Court of Justice case struck down the directive. The directive, of course, didn’t have in it all the checks and balances which we have in our domestic provisions. So by now putting into primary legislation the way that we ask for communications data to be retained by the service providers, we not only put it beyond any legal doubt – because before we were just relying on the directive to do all the legal heavy lifting – we now, like the Danes and others, put it into primary legislation. So we fill that legal vacuum that has been opened up by the court ruling.

We also at the same time put in a sort of shop front window through primary legislation, those checks and balances which will satisfy the court ruling and its comments on proportionality at the same time. So it does both – it both provides legal certainty, but also at the same time addresses the substance of the court’s ruling about the need for communications data to be retained in a way that is proportionate, accountable and so on.

Prime Minister

To answer your question about Snowden and warrants – I mean, I looked at this very carefully post Snowden, and my conclusion is that at the heart of our system is a very sound set of measures, as I’ve said. If the intelligence services want to listen to someone’s telephone call, they’ve got to have a signed warrant by the Home Secretary, an elected Parliamentarian accountable to Parliament, that’s overseen by the Interception Commissioner and then examined by the Intelligence and Security Committee.

And Sir Anthony May, in his report this year, you know, went through that in quite a lot of detail and put more information in the public domain than had been done previously, and I think that’s the best account I can possibly provide for how our system works, and why, in a mature, liberal democracy, it’s a good and strong system. And I’d really recommend you’d look at that.

What we’re doing today is adding some extra balances and braces, some more transparency, another oversight panel, some more powers for the Intelligence and Security Committee. These are important additional safeguards. But my argument is, at the heart of our system, what I explain to people – because often people ask me about this, you know; do we have too intrusive intelligence and security services in our country. When I explain to people that in order to intercept someone’s telephone, there has to be a signed warrant by the Home Secretary overseen by an Intercept Commissioner, accountable to a Parliamentary committee, actually people can see that there’s a very strong safeguard.

And I think when people do understand the difference between that – the content of a communication, with all those safeguards. The difference between that and the fact of a communication, which obviously the police use in so many cases. I think people understand we have a strong system.

I think we probably have time for 2 more, let’s have – shall we have Sky News and ITV? I think would be a fair balance.

Question

What do you say to those critics who are already saying that today’s drama is really an attempt to distract public attention from the strikes and also from political embarrassments over paedophiles?

And secondly, are you sure this is going to work? I mean, given the international dimension of communications, is this actually going to be good law that is going to be effective, that’s going to make, for example, American telecom companies cooperate with the government in the way that you’d like?

Prime Minister

Well, first of all, in terms of distraction, I mean, there’s never a good day to do these things; it’s just, you know, we’re running out of time in this Parliamentary session. We need to take this legislation through, we wanted to agree a proper set of safeguards and a proper approach; we’ve done that, and we’re announcing it at the first available opportunity.

And the Home Secretary is making a statement in Parliament, and so I think it’s the right way to proceed. In terms of ‘will it work’, my understanding is that a lot of the companies concerned want to have greater legal clarity, so they can continue to cooperate in the appropriate way; and this will help. And that’s clearly the aim behind what we’re doing.

Question

Carl Dinnen, ITV news. Just how close were we to the cliff edge, and how much danger was Britain in had we reached it?

Prime Minister

Well, I think the best way to describe – there are really 2 cliff edges. One is the communications data, the data that mobile phone companies keep about who made a call, when and who to, that wouldn’t have disappeared instantly. But of course once you’ve lost the legal backing of the European framework law, the danger is that companies would have to start destroying that data unless it was kept for a specific business use.

So that was not so much an absolute cliff edge, but you were looking down the telescope of a declining capability which the police, the National Crime Agency, the intelligence services were all warning us would be very, very serious for their capabilities. The second area, which is the lawful intercept area – the ability in extremis to listen to someone’s communications – that is more of a cliff edge, because if companies that up to now have been sharing this data are saying, “well, because of legal uncertainty we cannot share this data”, that would have serious consequences for counterterrorism and other work that is done by intelligence and security services to help keep this country safe. And a lot of material and information that we would be otherwise able to receive, we would not be able to receive.

And I wouldn’t be standing here, announcing these extra powers, if I didn’t believe there was a real danger to the United Kingdom of not acting. I think there is a real danger and that’s why I’m recommending this action. And I believe that parliament should – should pass this bill and agree the safeguards that we are setting out.

Deputy Prime Minister

The answer is within a matter of weeks, otherwise we would have deferred this until after recess. But on both the legal vacuum which was opened up by the cases which were stayed while the European Court of Justice ruling was made, and because of the growing uncertainties around the application of the RIPA act to service providers that might be based elsewhere, but provided service in the United Kingdom, our judgement – the judgement of the leader of the opposition, judgement we’ve arrived at across parties – is we need to act now before the recess because doing so afterwards would simply be too late.

What does too late mean? It means that capabilities which we’ve all taken for granted for a long period of time and have been operating for years, and years, and years, would suddenly no longer be available to us and would have a very material effect on our safety.

So that is why we’re acting as we are and not doing so in the autumn.

Prime Minister

Thank you very much. Thank you.