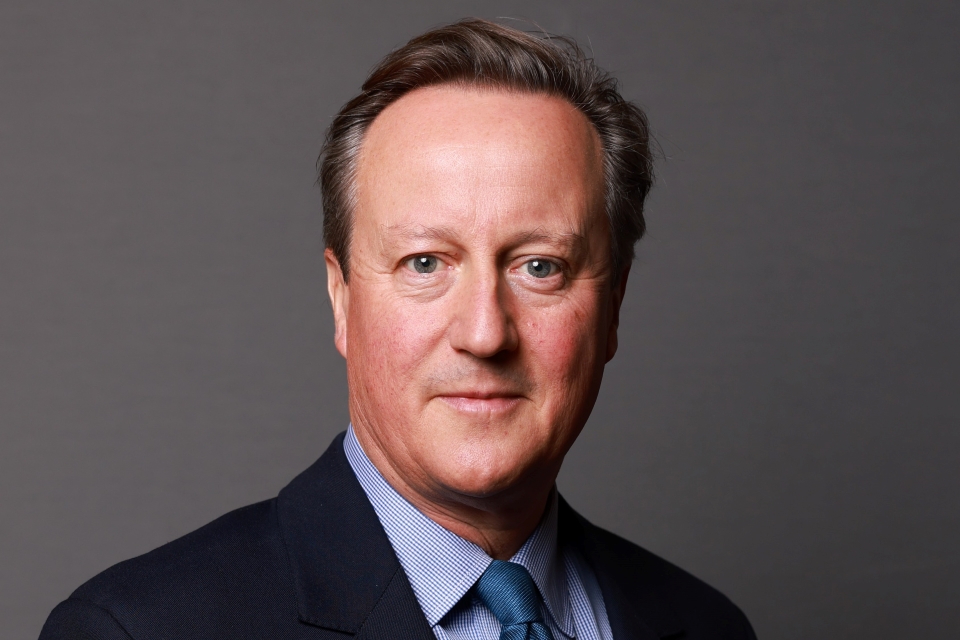

Prime Minister's speech on the economy

A transcript of a speech on cutting the deficit given by the Prime Minister in Milton Keynes on 7 June 2010.

Prime Minister

Today my speech is about the deficit and the debt and the financial problems that we face. But at the same time as that we must never take our eyes off the need for building strong and sustained economic growth in Britain, growth in which our universities – and perhaps the Open University in particular – should play a huge part.

The knowledge-based economy is the economy of the future, and in building that economy and in recognising that it is not just about young people’s skills but about people’s skills all through their lives, the Open University has a huge, huge role to play. It is a great British innovation and invention and it is a privilege to be here this morning.

I have been in office for a month and I have spent much of that time discussing with the Chancellor and with government officials the most urgent issue facing Britain today, and that is our massive deficit and our growing debt. How we deal with these things will affect our economy and our society, indeed our whole way of life.

The decisions we make will affect every single person in the country and the effects of those decisions will stay with us for years, perhaps even decades, to come. And it is precisely because these decisions are so momentous, because they all have such enormous implications and because we cannot afford either to duck them or to get them wrong, that I want to make sure we go about the urgent task of cutting our deficit in a way that is open, responsible, and fair.

I want this government to carry out Britain’s unavoidable deficit-reduction plan in a way that tries to strengthen and unite our country at the same time. I have said before that as we deal with the debt crisis we must take the whole country with us, and I mean it. George Osborne has said that our plans to cut the deficit must be based on the belief that we are all in this together, and he means it.

Tomorrow, George Osborne and Danny Alexander will publish the framework for this year’s Spending Review. They will explain the principles that will underpin our approach and the process we intend to follow including, vitally, a process to engage and involve the whole country in the difficult decisions that will have to be taken.

But today, I want to set out for the country the big arguments that form the background to the inevitably painful times that lie ahead of us. Why we need to do this, why the overall scale of the problem is even worse than we thought and why its potential consequences, and the consequences of inaction, are therefore more critical than we originally feared.

There are three simple reasons why we have to deal with the country’s debts. One: the more the government borrows, the more it has to repay; the more it has to repay, the more lenders worry about getting their money back; and the more lenders start to worry, the less confidence there is in our economy.

Two: investors – people lending us this money – they do not have to put their money in Britain. They will only do so if they are confident the economy is being run properly, and if confidence in our economy is hit, we run the risk of higher interest rates.

Three: the real, human, everyday reason this is the most urgent problem facing Britain, is that higher interest rates hurt every family and every business in our land. They mean higher mortgage rates and lower employment. They mean that instead of your taxes going to pay for the things we all want, like schools and hospitals and police, your money, the money you work so hard for, is going on paying the interest on our national debt. That is why we have to do something about this.

This argument that we have consistently made, for urgent action to start tackling the deficit this year and an accelerated plan for eliminating it over the years ahead, has already been backed by the Bank of England and the Treasury’s own analysis. It has been made more urgent still by the sovereign debt crisis in the Eurozone over recent months. The global financial markets are no longer focusing simply on the financial position of the banks. They want to know that the governments that have supported the banks over the last 18 months are taking the actions to bring their own finances under control.

This weekend in South Korea, George Osborne received explicit backing from the G20 for the actions this government has already taken. Around the world people and their governments are waking up to the dangers of not dealing with their debts, and Britain has got to be part of that international mainstream as well.

So we are clear about what we must do. We have also been clear about how we must do it – as the Deputy Prime Minister has said – in a way that protects the poorest and the most vulnerable in our society, in a way that unites our country rather than divides it, and in a way that demonstrates that we are all in this together.

And we should be clear too that these problems have not just appeared overnight. [Party political content]. Now that we have had a chance to look at what has really been going on, I want to tell you the scale of the problem that we face.

We have known for a long time that our debts are huge. Last year, our budget deficit was the largest in our peacetime history. This year – at least according to the previous government’s forecasts – it is set to be over 11% of GDP, of our whole national income.

Today, our national debt stands at £770 billion. Within just five years it is set to nearly double to £1.4 trillion. To put it in perspective, that is some £22,000 for every man, woman and child in our country.

Now, we knew this before. Soon, the independent Office for Budget Responsibility will set out independent forecasts that will show the scale of the problem we are in today. For the first time people will be able to see a really truly independent assessment of the nation’s finances and the size of the structural deficit.

This important innovation has been noticed around the world, and I believe will help restore confidence in our fiscal framework. But what I can tell you today – and what we did not know for sure before, in fact what we could not know, because the previous Chancellor of the Exchequer did not make the figures available – is how much the interest on our debt is likely to increase in the years to come.

We have looked at the figures and, based on the calculations of the last government, in five years’ time the interest we are paying on our debt – the interest alone, not the debt itself – is predicted to be around £70 billion. That is a simply staggering amount. [Party political content.]

Let me explain what it means. Today we spend more on debt interest than we do on running our schools. But £70 billion means spending more on debt interest than we currently do on running our schools in England, plus on combating climate change, plus everything we spend on transport. Interest payments of £70 billion mean that for every single pound you pay in tax, 10 pence would be spent on the interest on our debt. Not paying off the debt itself, just paying the interest on the debt.

Is that what people work so hard for, that their hard-earned taxes are blown on interest payments on the national debt? Think about it another way: corporation tax raises £36 billion a year, so all the money from all the tax on all the profits on every single company in Britain just pays a little bit more than half of the interest on our national debt. That is how serious this problem is. What a terrible, terrible waste of money.

So, this is how bad things are. This is how far we have been living beyond our means. That is the legacy that our generation threatens to leave the next unless we act. So no one can deny the scale of the problem, and that the scale is huge. But what makes this such a monumental challenge is the nature of the problem.

There are some who say that our massive deficit is just because we have been in a recession, and that when growth comes back everything will somehow be okay. But there is a flaw in this argument and it is rather a major flaw: we had a significant deficit problem way before the recession. In fact, much of the deficit is what they call ‘structural’. A problem built up before the recession, caused by the government spending and planning to spend more than we could afford. It had nothing to do with the recession and so a return to growth will not sort it out.

This really is the crux of the problem we face today and the reason we can’t just sit here and hope for the best. The previous government really did think that they had abolished boom and bust. They thought the good times would go on forever; the economy would keep on growing and they could keep on spending.

But the truth about that economic growth – and the tragedy – is that it was based on things that could never go on forever. The economy was based on a boom in financial services, which at its peak accounted for a quarter of all corporation-tax receipts. But this was unsustainable because the success of financial services – a great and important industry – was partly an illusion, conjured from years of low interest rates, cheap money and a bubble in the price of assets like houses.

The economy was based on a boom in immigration, which at one point accounted for a fifth of our annual economic growth. But this was unsustainable because it is just not possible to keep bringing more and more people into our country to work while at the same time leaving millions of people to live a life on welfare.

The economy was based on a boom in government spending, with some budgets doubled or even trebled in a decade. Again, this was not sustainable because, in the end, someone has to pay for all that spending. So when the inevitable happened and when the boom turned to bust, this country was left high and dry with a massive deficit that threatens to loom over our economy and our society for a generation. So the problem we face today is not just the size of our debts, but the nature of them.

[Party political content.]

We are now publishing the information about how all your money is spent. We are shining a spotlight on where the waste went and it is a scandalous sight to see: a Department for Work and Pensions that increased benefit spending by over £20 billion and gave some families – some individual families – as much as £93,000 in housing benefit every year; a Ministry of Defence that allowed 14 major projects to overrun, which at the last count are between them £4.5 billion over budget; a Department of Health which almost doubled the number of managers in the NHS; and a Treasury that sanctioned all of this because it published growth forecasts that were far more optimistic than independent forecasters’.

And look at how [this was done] while at the same time doing so much damage to the fundamentals of our economy: letting it get completely out of balance by hitching our fortunes to a select few industries; accepting as a fact of life that eight million people are economically inactive in our country; and allowing our economy to become far too dependent on a public sector whose productivity was falling; and far too hostile, I would argue, to a private sector that has now actually shrunk in size to a level not seen since 2004.

Nothing illustrates better the total irresponsibility of this approach than the fact that [party political content] unaffordable government spending [increased] even when the economy was shrinking. By the end of last year our economy was 4% smaller than in 2007. But if you look behind the headline figures, you see why we face such a massive deficit crisis today: because while the private sector of the economy was shrinking, the public sector was continuing its inexorable expansion. While everyday life was tough for people who didn’t work in the public sector with job losses, pay cuts, reduced working hours, falling profits, for those in the public sector, life went on much as before.

Since 2007 public spending has actually gone up by over 15% – some extra £120 billion in just three years. And while private-sector employment fell in this period by 3.7%, public-sector employment actually rose. So it has been, if you like, a tale of two economies: a public-sector boom and a private-sector bust.

But there was a problem with this public-sector splurge. The previous government argued that more spending would support the economy, conveniently forgetting that if you start with a large structural deficit, you ramp up spending even further, which is actually going to undermine confidence and investment, rather than encourage it. So, while the people employed by the taxpayer were insulated from the harsh realities of the recession, everyone else in the economy was starting to pay the price.

And now, today, we’re all paying the price because the size of the public sector has got way out of step with the size of the private sector. We’re going to have to try and get it back in line and that will be much more painful than if we had kept things properly in balance all along.

And the final part of the legacy is the fact the money the government put in to the public sector did not make it dramatically better or more efficient.

So, while the cutbacks that are coming are unavoidable now, they could have been avoided if previously we had spent wisely instead of showering the public sector with cash at a time when everyone else in the country was tightening their belt.

So that is the overall scale and nature of the problem. And I want to be equally clear about what the potential consequences are if we fail to act decisively and quickly to cut spending, to bring our borrowing down and to reduce our deficit.

If we do nothing, there are three possible scenarios. As we have seen, the best-case scenario is that we pay increasingly punishing amounts of interest on our debt, dozens of billions every year without ever actually paying our debts off. That huge drain on the public finances would threaten the money that could have been spent on the things we really want to spend it on: improving the NHS; giving our children a better education; investing in our country’s infrastructure. This, the best-case scenario, I would describe as dire, unprogressive, a bad outcome for our country.

But, as I say, that’s the best case. If we fail to confront our problems we could suffer worse, a steady, painful erosion of confidence in our economy, because today almost every major country in the world is focusing on the need to cut their deficits. And the G20 has called on those countries with the biggest deficits to accelerate their plans for reducing them.

If, in Britain, investors saw no will at the top of government to get a grip on our public finances, they would doubt Britain’s ability to pay its way. That means they would demand a higher price for taking our debt, interest rates would have to rise, investment would fall. If that were to happen, there would be no proper growth, there would be no real recovery, there would be no substantial new jobs because Britain’s economy would be beginning a slide to decline.

These outcomes would be nothing less than disastrous, in my view, not just for our economy but for our society too, and our vision of a Britain, which we want to see, that is more free, more fair and more responsible.

But even more worrying is the example of Greece – a sudden loss of confidence and a sharp increase in interest rates. Now, let me be clear: our debts are not as bad as Greece’s; our underlying economic position is much stronger than Greece’s; and crucially we now have a government that I would argue has already demonstrated its willingness and its ability to deal with the problem. But Greece stands as a warning of what happens to countries that lose their credibility, or whose governments pretend that difficult decisions can somehow be avoided.

Thankfully this is a warning that has now focused the attention of the international community. This is why we believe there is only one option in front of us: to take immediate and decisive action. That’s why we have already launched and completed an in-year Spending Review to save £6 billion of public spending.

It’s why, shortly, our new, independent Office for Budget Responsibility will set out independent forecasts for both our growth and borrowing so that never again can this country sleepwalk into such a massive debt crisis. Our actions have already been noticed around the world, and I’m glad the G20 summit this weekend explicitly endorsed the decisions we have taken.

So this is the sober reality that I have to set out for the country today. The legacy left [party political content] is terrible. The private sector has shrunk back to what it was over six years ago. Unless we act now, interest payments in five years’ time could end up being higher than the sums we spend on our schools, on climate change and on transport combined.

Because the legacy we have been left is so bad, the measures that we need to deal with it will be unavoidably tough. But people’s lives – and this is vital – people’s lives will be worse unless we do something now. The cause of building a fairer society will be set back for years unless we do something now. We are not alone in this; many countries around the world have been living beyond their means and they too are having to face the music. And I make this promise to everyone in Britain: you will not be left on your own in this. We are all in this together and we are going to get through this together. We will carry out Britain’s unavoidable deficit-reduction plan in a way that strengthens and unites the country.

We are not doing this because we want to. We are not driven by some theory or some ideology. We are doing this as a government because we have to, driven by the urgent truth that unless we do so, people will suffer and our national interest will suffer too. But this government will not cut this deficit in a way that hurts those we most need to help, in a way that divides our country or in a way that undermines the spirit and ethos of our vital public services.

Freedom, fairness, responsibility: those are the values that drive this government; they are the values that will drive our efforts to deal with our debts and to turn this country around.

So yes, it will be tough. I make no bones about that, but we will get through this together and Britain and all of us will come out stronger on the other side. Thank you for listening.

Question

Prime Minister, you say we’re all in this together. Does that include the right-wing of your party, who have been lobbying so hard against any tax rises?

Prime Minister

That includes everybody. I mean I would argue the government immediately signalled the sign that we’re all in it together by actually saying that we’ve got to start with ourselves, that ministers should take a pay cut, that ministerial limousines should be cut back, that we’ve got to make sure Parliament costs less money and, yes, it does mean that we have to carry through tax policies, some of which we inherited from the previous government in terms of top rates of tax, as part of the picture. ies,’ and I think this is the sort of country that wants its government to go on being compassionate in that way, just as the people of this country themselves are compassionate when it comes to Red Nose Day or Comic Relief or all those other events where people give so generously.

So I think picking out those two areas is right, and it will help us to make the moral argument about what sort of country this is as we deal with the incredibly difficult decisions that we have in front of us. That’s what the coalition has to do. It is going to be a very, very difficult task, but I believe it’s a task that actually helps to bring us together in this common endeavour of making sure that at the end of this five-year period, at the end of a Budget and a spending round that will be difficult, that actually people say we sorted out our problems, we paid down our debts, we found our way in the world again, we started to grow again, we started to get an economy that was about jobs and living standards and things that we want. That’s what this is about: yes, difficulties, but, as I said in the speech, we’ll come through it together and in the end we will come through it stronger and it’ll be something that Britain will be able to turn round to others in the world and say we did this important thing. It needed to be done, we did it, we did it well, and we’re a better off country as a result of it. That’s what this challenge is about.

Thank you very much for coming. Thank you to the Open University again and thank you very much for listening. In terms of capital-gains tax, I think people understand we need to raise some modest additional revenue from capital-gains tax to pay for the increase in tax allowances that we all want to see to help the low paid, to help protect, as I said, the people that we want to help most at this time.

And I think people also understand, and actually if you read any of the things written by anyone who is concerned about capital-gains tax, they all understand this massive leakage of revenue that takes place when you have a very low rate of capital-gains tax and a very high rate of income tax. And clearly it would be irresponsible to allow that massive leakage to take place; we do need to be in a position where we get our deficit down. I think people understand that, but they know that there’ll be an answer in the Budget and I hope that will be an answer that people will find shows that we’ve addressed the concerns that people understandably have.

Question

Thank you, Prime Minister. You say these cuts will affect our whole way of life, that they will affect every individual in the country, and yet you still have not spelt out any area that you’re looking for which will be painful to people. When will you start to do that? And when ministers make comparisons with, say, Canada, they blew up a hospital in Canada, they made redundant tens of thousands of people, they cut benefits too; is that what Britain has to look forward to?

Prime Minister

Well, what I would say is this: that we’ve got a proper process for doing this, a process where we have a Budget on the 22nd of June where we’ll set out the spending over the next three years and then I want to see a proper debate take place, that involves as many people as possible, that will lead to the actual spending reductions in departments being set out and what the consequences of those spending reductions are, and I want us to go about this in the best way possible, to take people with us.

What I would say about Canada – and I was speaking to the Canadian Prime Minister about this just last week – while they do stand as an example of a government (it was a previous government) that sorted out a debt and a deficit crisis, the great warning they give is that actually they put it off for too many years before they did it, so the problem they had to solve was even worse by the time they got round to it. I’m determined, seeing the figures as I can now see, understanding the warnings which I made before but make again today, that we shouldn’t put this off. We need to get on with what needs to be done. Yes, we need to take people with us, yes, it will mean difficult departmental decisions, and, yes, it will inevitably mean some difficult decisions over big areas of spending like pay and pensions and benefits, and we need to explain those to people.

But I profoundly believe that government is about acting in the national interest. It is our national interest to do this, and it’s in our national interest to try and take the country with us as we do it, but ducking the decisions would be a complete betrayal of what I believe in, which is government, public interest, national interest, doing the right thing. If this is the right thing to do, we must be able to convince people that it’s the right thing to do, and irrespective of how unpopular some of these decisions will be, we will, I think, in the long run, be able to take people through to a brighter economic future beyond.

Question

Just quickly, you’re saying people will get a sense of what this might involve, come the autumn and the spending round? Or within weeks?

Prime Minister

There will be difficult decisions in the Budget, undoubtedly. There will then be discussions over the summer about public spending and public spending changes that are going to have to be made in different departments and, as I say, these will be relatively open discussions, because once you start setting a spending envelope for the next three years – something the last government didn’t do. [Party political content]. Once you do that, people will see the sorts of choices that we, with them, will have to make. Perhaps Danny would like to say something about it a week into looking at some of those difficult choices.

Danny Alexander MP

Yes, thank you, Prime Minister. I mean, I’ve spent the last week looking over the books and obviously announcements will be made in the Budget and then in due course in the Spending Review, but I’m in no doubt at all, having done that, that the approach we’re setting out today is exactly the right thing to do. Because, there has been irresponsibility in the way that the previous government handled the public finances and we have to bring responsibility to the way that we do that. That’s the point of this agenda, and, in a sense, what we’re setting out today is, if we don’t take responsibility in the way that the Prime Minister has set out, what are the consequences of that? The £70 billion that we’d end up spending on debt repayments, for example, the consequence that has for money that you can’t spend on public services. That’s why, when you look at all the other options, no matter how painful what we have to do might be, we have to do it.

Prime Minister

Don’t put off what needs to be done is the thing to bear in mind.

Question

I’m interested that you say you want to engage and involve the whole country in this very painful cutting process that has to happen. It sounds good, it also sounds like it might be little more than a talking shop. How are you going to convince people that you’ll not only listen to them, but that you’ll also act on what they want and don’t want to happen?

Prime Minister

Well, that’s, to me, what politics should be about. I mean, we the politicians have got a duty, I think, to explain to the country the nature and scale of the problem. I’ve tried to do that today. I’ve tried to explain what happens if we don’t do anything, if we just sat back, took the easy course, enjoyed being in office and making decisions and having meetings, just sat there, what would happen? And actually, the consequences would be very dire. So we’ve set out the envelope, as it were, of what needs to be done. Then I think there needs to be a discussion following the Budget about, well, what are the priorities, what are the things we need to protect most of all, what are the difficult decisions that we could take, and involve people.

I don’t want to spend a lot of money doing this – there isn’t any money, as one of your predecessors put it so clearly – but I think it is a good idea to take people with you, have this discussion and debate about education spending, about whether we’re spending on transport, infrastructure, how much you try and protect capital spending, all those things, have a discussion with people, and then at the end, obviously, we have the Spending Review where you have to make your announcements.

Inevitably, we are going to make a lot of decisions that people won’t agree with, but we have to convince people first that the big decision, the need to reduce spending and get the deficit under control, is the right one, and I think once you’ve done that, then people, even if they don’t accept some of the individual decisions – because all these choices are hard choices – we can take people with us on the basis that the alternative, the doing nothing, the sitting back, the pretending somehow this is all going to be cured by growth, that would be incomparably weak. That’s what we have to try and do.

Question

Mr Prime Minister, is there a danger, in this globalised world, that by talking about things being far worse than you expected that you perhaps could be seen to be talking down the British economy which could be taken unfavourably by the markets? And also, you talk about uniting the country – isn’t there a danger that you’ll succeed not in doing that but in uniting the country against you and your government?

Prime Minister

Let me take both of those. I think there would be a danger in what you say if we hadn’t, as a government, already taken action. We’re not just arriving in government and saying, ‘Oh, look, this is all, you know, terrible.’ We’ve arrived in government and immediately had a mini-spending round and reduced spending by £6 billion in-year, so we have sent a very strong signal about that this is a government that recognises the problem, but also wants to take action to deal with the problem, and I think what I’ve set out today is a very calm and clear analysis of how bad the problem is and what the consequences are of not taking action, but I think people can judge us by what we have already done and then obviously judge us on the Budget that we announce, the spending figures we announce, the plans for the rest of the Parliament and that, I think, is what people will rightly want to hear.

Is there a danger we could unite people against us? This is fraught with danger. This is a very, very difficult thing we are trying to do. You know, I went to address all the peers in the House of Lords before the election. I remember looking round the room and there were all these great figures from the past, of Geoffrey Howe and Nigel Lawson, and no one in this country has had to deal with an 11% budget deficit before. Why? Because we haven’t had one before. This is worse than anything that people have had to deal with before, and so yes, there are great risks and great difficulties in dealing with it, but to me, the challenge of statesmanship is to take difficult decisions in the national interest because it’s the right thing to do, and you have to try and take people with you as you do that, but what is clear to me is an even easier way of uniting the entire country against you would be sitting back and waiting for the realisation to grow that Britain’s economy was hopelessly in debt, debt interest payments were eating up all of the hard-earned taxes that everyone in this room and beyond pays, and that the government was just too weak and feckless to do something about it.

We have to act, we have to convince people it’s the right thing to do, and then we have to do our best to take them with us on the difficult decisions along that path. That is what this is all about. It’s not meant to be easy, it is incredibly difficult, no one’s done it before, but we have to do our very best to deal with it and I believe that we can. And I think the coalition helps us, because we have two parties together actually facing up to the British people and saying, ‘Both of us have come to this judgment that it’s the right thing to do, and we’re going to carry this through together and we’re going to try and take you with us as we do so.’

Question

Thank you, Prime Minster. If the situation is so much worse than you previously thought, isn’t it time to take the difficult decisions as you suggest and look again at ring-fencing, protecting particular budgets, like sending billions of pounds of taxpayers’ money overseas and the Health Service, because surely everything should be up for grabs? And also, if I may, if the public sector has got too big, how much smaller should it be? Do you have any sense of the kind of share of the economy it could/should take up?

Prime Minister

I don’t believe in announcing some sort of pre-conceived share of what the government should account for in an economy; I believe in trying to get the economy growing, trying to get the private sector moving, trying to fire up the engines of entrepreneurialism so actually we have a more affordable situation, that’s what needs to happen.

In terms of the areas that we’ve ring-fenced, I think there are good reasons for them, and part of them are about what sort of country we want this to be. You know, the NHS is one of the most essential things for every family in our country, and I think it sends a very positive message to say to people: ‘yes, we are going to have to take difficult decisions, yes, there are going to have to be public spending programmes that are going to have to be cut, yes, there may be things that the government did in the past that it can’t do in the future, but when it comes to the service that every family absolutely wants to be there and provide the best they possibly can for their families, we’re going to protect that. So as we take these difficult decisions, a well-funded NHS (because health is the most important thing in your life) will be there for you.’

Again, on the issue of overseas aid, I would say that there is a very good moral argument. Britain has built a place in the world about sticking to our word on our aid commitments, and we can hold our heads up in the G20 or the EU or in any other forum in the world, on the basis that this is a generous country, a compassionate country, that even when we’re dealing with our difficult problems, we send money to other parts of the world where people are living on a dollar a day or less. And the fact that you can look in the eyes of the French politician, the Italian politician and many others and say, ‘Well, sometimes you may not say that Britain is engaged enough in these forums, but when it comes to the promises we make, we stick to them, and we stick to them on behalf of people who are living in incredible poverty, with huge difficult