Main report for the Participation Survey (May 2023 to March 2024)

Updated 13 February 2025

Applies to England

February 2025 - A small number of figures have had revisions due to a minor processing error. The corresponding data tables and this report have been updated. We expect we may make a small number of similar minor revisions at the end of March, but not to any of our headline indicators.

1. Background

- Released: 24th July 2024

- Geographical Coverage: England

This release provides estimates on engagement in the digital, culture, media, and live sport sectors reported during the period of May 2023 to March 2024 (2023/24). The Participation Survey is a nationally representative annual survey of adults (16+) in England that aims to track the latest trends in engagement in DCMS, Arts Councils England (ACE), and digital sectors[footnote 1]. The format of the survey is push-to-web, with a paper version for those who are not able or wish not to complete this online.

This report presents the headline estimates during May 2023 to March 2024, and demographic breakdowns[footnote 2] of adults who have engaged in the specific sectors covered in the survey. Further estimates can be found in the accompanying data tables. Differences between groups are only reported on in this publication where they are statistically significant, that is, where we can be more confident that the differences seen in our sampled respondents reflect the population[footnote 3]. Estimates for the final quarter of 2023/24 (January to March 2024) have also been published in a separate set of data tables, alongside the first three quarters of the survey year.

It should be noted that most questions in the survey ask about engagement with cultural and digital activities in the last 12 months (such that it covered the period May 2022 to March 2024). Comparisons of this year’s 2023/24 results are made against the previous year 2022/23 (covering the period of April 2022 to March 2023).

In 2023/24, DCMS partnered with ACE to boost the Participation Survey to be able to produce meaningful estimates at Local Authority level. This has enabled us to have the most granular data we have ever had. It also means there are some new questions and changes to existing questions, response options and definitions in the 2023/24 survey.

Where there has been a change, we have highlighted where a comparison with previous data can or cannot be made. Questionnaire changes can affect results, and therefore should be taken into consideration when interpreting the findings.

2. Arts

Examples of physical arts engagement include reading, performing music, or going to a comedy event. Examples of digital arts engagement include watching live-streamed or recorded theatre, participating in live visual arts programs, or listening to pre-recorded music or dance events. The full list of qualifying activities[footnote 4] and events we asked about are in Annex 3, and shown in Figures 2.4 and 2.5. All estimates in this chapter (excluding the grey box below) are based on DCMS’ definition of the arts sector, as outlined in Annex 3.

Headline findings

During May 2023 to March 2024 (2023/24): 91% of adults engaged with the arts at least once in the last 12 months, a 1 percentage point increase from 2022/23 (90%).

Figure 2.1 shows that 90% of adults had engaged with the arts physically in the previous 12 months before being surveyed, a 1 percentage point increase from 2022/23 (89%). The corresponding figure for digital engagement was 36%, an 8 percentage point increase from 2022/23 (28%).

Figure 2.1: Engagement with the arts sector, England: 2022/23 – 2023/24 (Base: All adults).

Figure 2.2 shows that of the 91% of adults who engaged with the arts, 55% of adults engaged exclusively physically, whilst 35% engaged both physically and digitally and only 1% engaged exclusively digitally.

Figure 2.2: Physical and digital engagement with the arts sector, England: 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

Figure 2.3 shows that of those who engaged with the arts physically, the most frequent level[footnote 5] at which adults attended any arts event or participated in any arts activity was once a week (59%). Whereas, of those who digitally engaged with the arts the most frequent level at which adults engaged with the arts sector online was three to four times a year (33%).

Figure 2.3: Most frequent level of physical and digital engagement with the arts sector, England: 2023/24 (Base: Adults who physically or digitally engaged with the arts)

Figure 2.4 shows that the most popular way to engage with the arts physically was reading books or magazines (64%). This was followed by cinema screening of a film or movie (55%) and a theatrical performance (39%).

Figure 2.4: Form of physical engagement with the arts sector, England: 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

Figure 2.5 shows that for digital engagement, watching a pre-recorded music or dance event was the most popular (21%). Around 17% of adults reported that they watched a live music or dance event as it was happening, whilst 10% of adults reported that they watched a pre-recorded arts event including theatre, visual arts or literature. This was similar to the previous year (2022/23).

Figure 2.5: Forms of digital engagement with the arts sector, England: 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

Of those who did engage digitally with the arts, nearly half of respondents (49%) said ‘content is paid for through TV licence fee’ and 46% said they accessed ‘free content’. Nearly a quarter (24%) of adults paid ‘a monthly or annual subscription’. Only 2% reported they accessed ‘paid content for free, using other methods’ and similarly only 2% reported they accessed ‘content using a log-in belonging to someone not in their household’.

Attendance, participation or watching arts events or activities covered by ACE’s policy remit

Arts Council England (ACE) is the national development agency for creativity and culture. They invest in artists, arts organisations, museums and libraries, and provide development opportunities for this sector[footnote 6]. As part of our partnership with ACE, we have published additional estimates for the proportion of adults who attended, participated in or watched arts events or activities covered by ACE’s policy remit. Options within the survey which would fall within this remit include:

Attendance:

- An exhibition of art, photography or sculptures

- A theatre play, drama, musical, Pantomime, Ballet or Opera

- An event connected with literature, books, reading, poetry reading or writing

- A craft exhibition

- A live music event

- An arts festival and or carnival

- A street art event

- A live dance event

Participation:

- Written stories, plays, or poetry

- Written, practised or performed music

- Painting, drawing, printmaking, calligraphy, colouring

- Crafts

- Choreographed or performed a drama or dance routine

- Photography as a hobby

Watched online:

- A live arts event including theatre, visual arts or literature

- A pre-recorded arts event including theatre, visual arts or literature

- A live music or dance event, watched as it was happening

- A pre-recorded music or dance event

In 2023/24, 78% of adults attended an art event in person, or participated in an art activity in person, or watched online an arts event covered by ACE’s policy remit, in the last 12 months. Of which:

- 65% of adults attended an art event in person in the last 12 months.

- 45% of adults participated in an art activity in person in the last 12 months.

- 36% of adults watched an art event online in the last 12 months.[footnote 7]

Further data is published in the accompanying datasets.

Who engaged with the arts?[footnote 8]

Figure 2.6 shows that in 2023/24:

-

Age: There was some variation in how people of different ages physically engaged with the arts. For example, adults aged 85 and over (86%) were less likely to engage with the arts physically than adults from all other age classifications presented here. Similarly for digital engagement, there was also some variation, for example adults aged 85 and over (29%) were less likely to engage with the arts digitally than adults from all other age classifications presented here.

-

Disability Status: For both physical and digital engagement with the arts, there were no differences observed between disabled adults and non-disabled adults.

Figure 2.6: Physical and digital engagement with the arts sector, by age and disability status, England: 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

Figure 2.7 shows that in 2023/24:

- Sex: Female adults (92%) were more likely to engage with the arts physically than male adults (89%). There were no differences in the level of digital engagement with the art sector by sex.

- Gender identity: For both physical and digital engagement with the arts, there were no differences observed between adults whose gender identity was the same as their sex registered at birth and adults who reported that their gender identity was different from their sex registered at birth.

- Sexual Orientation: Heterosexual or straight adults (91%) and adults in the “other” sexual orientation classification (90%) engaged less with the arts physically than gay or lesbian adults (95%) or bisexual adults (96%). Heterosexual or straight adults (36%) engaged the least with the arts digitally than all other sexual orientation classifications presented here (43–45%).

Figure 2.7: Physical and digital engagement with the arts sector, by sex[footnote 9], gender identity[footnote 10] and sexual orientation[footnote 11], England: 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

Figure 2.8 shows that:

- Religion: There was a lot of variation in how adults from different religious groups engaged with the arts. For example, Muslim adults (75%) engaged the least physically with the arts than adults from all other religious groups presented here (86–94%). Similarly, for digital engagement, Muslim adults (25%) engaged the least digitally with the arts than adults from all other religious groups presented here (31–47%).

- Ethnicity: There was a lot of variation in how adults from different ethnic groups engaged with the arts. For example, adults from the Pakistani ethnic group (73%) engaged less with the arts physically than all other ethnic groups presented here with the exception of adults from the Bangladeshi (77%), Arab (78%) or Gypsy or Irish Traveller ethnic group (80%). For digital arts engagement, similarly adults from the Pakistani ethnic group (22%) engaged less than all other ethnic groups presented here (30–47%), with the exception of adults from the Bangladeshi ethnic group (23%).

Figure 2.8: Physical and digital engagement with the arts sector, by religion and ethnicity, England: 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

| Bar label | Ethnicity | Bar label | Ethnicity | Bar label | Ethnicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Bangladeshi | G | Caribbean | M | Arab |

| B | Chinese | H | Any other black, African, or Caribbean background | N | Any other ethnic group |

| C | Indian | I | Mixed white and Asian | O | English, Welsh, Scottish, Northern Irish, or British |

| D | Pakistani | J | Mixed white and black African | P | Gypsy or Irish Traveller |

| E | Any other Asian background | K | Mixed white and black Caribbean | Q | Irish |

| F | African | L | Any other multi-ethnic background | R | Any other white background |

Figure 2.9 shows that:

- Socio-economic classification: There was some variation in both physical and digital engagement in the arts for adults of different socio-economic classifications. For example, for both physical and digital engagement in the arts, adults from the higher managerial, administrative and professional occupations classification (96% and 41%) engaged with the arts more than adults from all other socio-economic classifications presented here. Whilst adults from the never worked and long-term unemployed classification physically engaged with the arts (76% and 29%) less than adults from all other socio-economic classifications presented here.

- Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD): There was some variation in both physical and digital engagement in the arts for adults in different deprivation deciles. For example, adults from the highest decile (the least deprived) (95%) engaged the most with the arts physically compared to adults from all other deciles (82–94%), whilst adults from the lowest decile (the most deprived) (82%) engaged the least with the arts physically compared to adults from all other deciles (86–94%). Similarly for digital engagement, adults from the lowest decile (the most deprived) (30%) engaged the least with the arts digitally compared to adults from all other deciles (34–40%).

Figure 2.9: Physical and digital engagement with the arts sector, by socio-economic classification[footnote 12] and Index of Multiple Deprivation[footnote 13], England: 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

| Bar label | Socio-Economic Classification |

|---|---|

| A | Higher managerial, administrative, and professional occupations |

| B | Intermediate occupations |

| C | Routine and manual occupations |

| D | Never worked and long-term unemployed |

Geographical findings

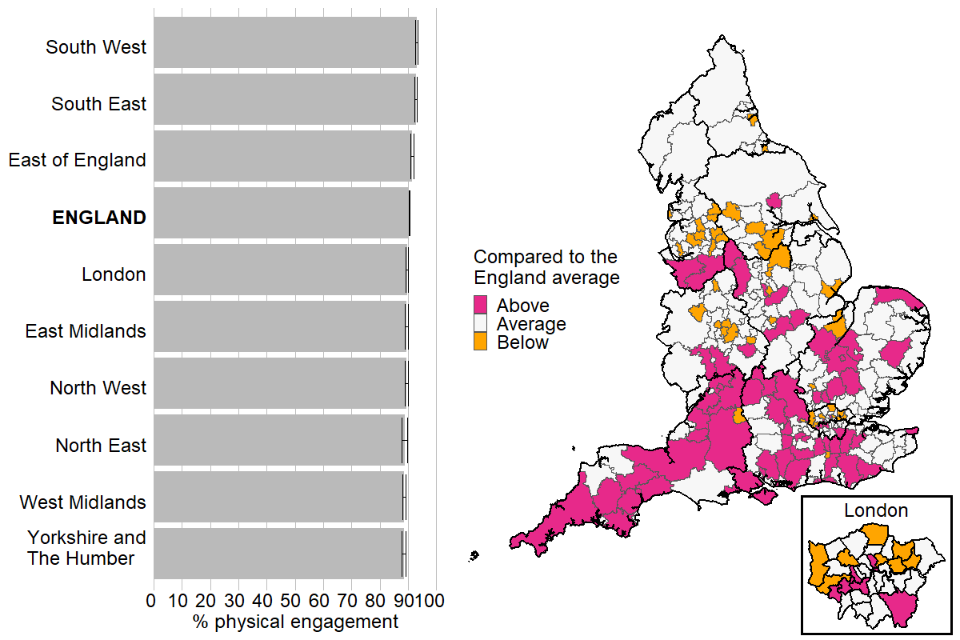

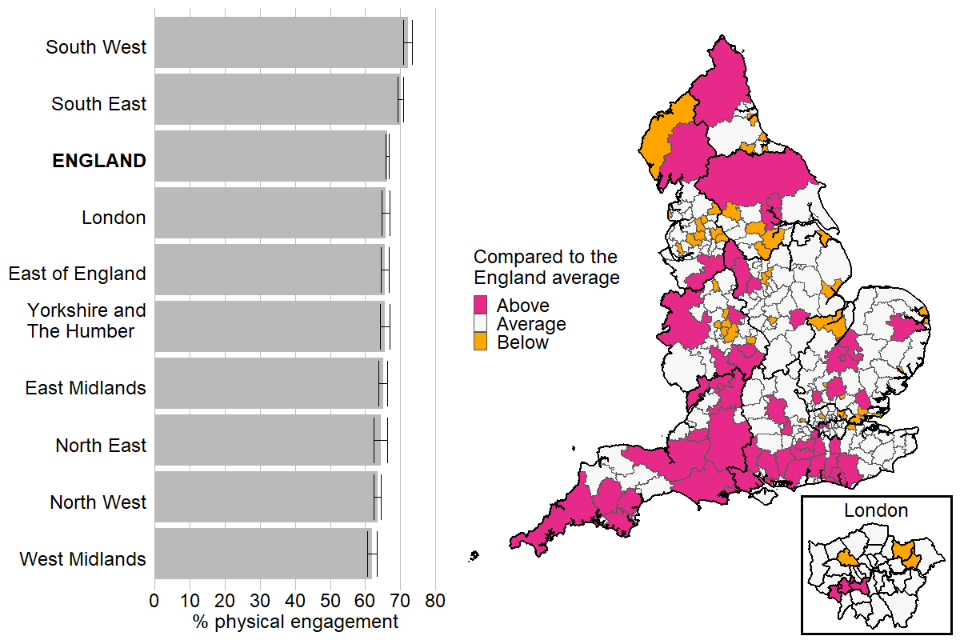

Figure 2.10 shows that there was a high proportion of physical engagement with the arts sector for adults of all regions, varying from 93% for adults in the South East and South West to 89% for adults in the North East, North West, West Midlands and the Yorkshire and the Humber regions.Of 296 LAs, 62% are not significantly different to the England average, with 24% above and 14% below, although some of these differences are small but significant. In general, the patterns of engagement at the regional level are also observed at the local authority (LA) level.

Some of the local authorities where physical art engagement was highest were in Chichester, South Cambridgeshire, City of London and Rutland (97%). Some of the local authorities where physical art engagement was lowest were in Leicester (80%), Slough (81%) and Blackburn with Darwen (81%).

Figure 2.10: Physical engagement with the arts sector, by Local Authority[footnote 14][footnote 15], England: 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

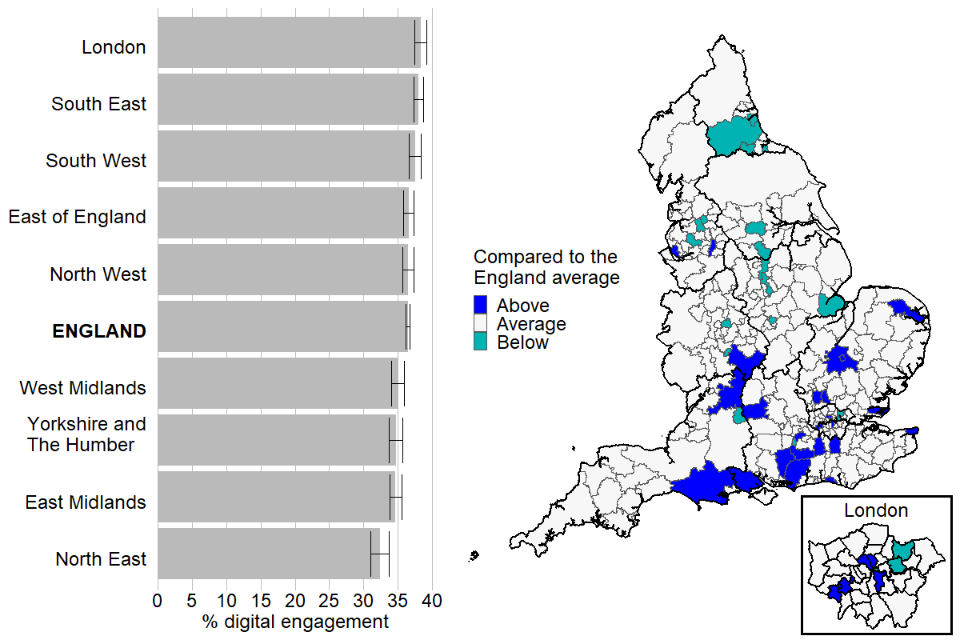

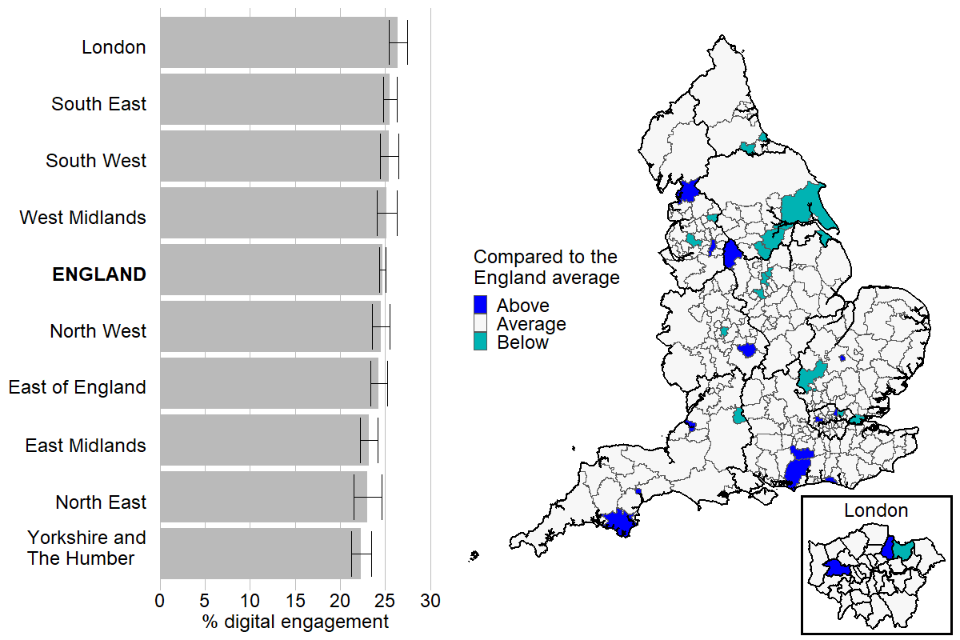

Figure 2.11 shows that adults in London (38%) and the South East (38%) regions digitally engaged with the arts more than the England average (36%), whilst adults in the South West (37%) engaged slightly more. Adults in the North East (32%) region digitally engaged with the arts less than the England average, whilst adults in the West Midlands (35%), Yorkshire and the Humber (35%) and East Midlands (35%) regions engaged slightly less .Of 296 LAs, 84% are not significantly different to the England average, with 9% above and 7% below, although some of these differences are small but significant. In general, the patterns of usage at the regional level are also observed at the local authority (LA) level. There are however some exceptions:

- In London (38%) and South East (38%) regions where digital engagement with the arts were above the England average, City of London (25%), Newham (30%), Redbridge (29%) and Rushmoor (31%) local authorities were lower than the average.

- In the West Midlands (35%) region where digital engagement with the arts was slightly lower than the England average, Stratford-on-Avon (43%) local authority was higher than the average.

Figure 2.11: Digital engagement with the arts sector, arts sector, by Local Authority[footnote 14][footnote 15], England: 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

Barriers to engagement

Respondents who did not engage with the arts were asked why they did not. The most common reasons given are shown in Figure 2.12 and were:

- For physical engagement, ‘No reason in particular’’ (28%) and ‘I’m not interested in cultural or arts activities’ (24%) were the most common barriers cited for not engaging with the arts sector.

- For digital engagement – ‘No reason in particular’ (41%) and ‘I cannot afford it’ (20%) were most commonly identified as barriers to engaging with the arts sector.

Figure 2.12: Reasons for not physically or digitally engaging with the arts sector, England: 2023/24 (Base: Adults who did not engage with the arts)

3. Libraries

Physical library engagement includes visiting a public library building or mobile library in-person during leisure time, being visited by a home library service and using another library outreach services (for example attending a community event where the library staff or volunteers were present). Digital engagement with libraries could include survey respondents using their online catalogue, paying fees online, or borrowing e-books and downloading audiobooks. The full list of included activities[footnote 4] we asked in the survey are in Annex 3 and shown in Figures 3.5 and 3.6.

Headline findings

During May 2023 to March 2024 (2023/24): 3 in 10 (30%) of adults engaged with the libraries at least once in the last 12 months, a 4 percentage point increase from 2022/23 (26%).

Figure 3.1 shows that 25% of adults had engaged with libraries physically in the previous 12 months to being surveyed, a 6 percentage point increase from 2022/23 (19%). The corresponding figure for digital engagement was 14%, a 1 percentage point increase from 2022/23 (13%).

Figure 3.1: Engagement with the libraries sector, England: 2022/23 – 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

Figure 3.2 shows that of the 30% of adults who engaged with the libraries, 16% of adults engaged exclusively physically, whilst 9% engaged both physically and digitally and only 5% engaged exclusively digitally.

Figure 3.2: Physical and digital engagement with the libraries sector, England: 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

Figure 3.3 shows that of those who engaged with the libraries physically, the most frequent level at which adults attended any library event or participated in any library activity was three to four times a year (34%). Similarly of those who digitally engaged with the libraries, the most frequent level[footnote 16] at which adults engaged with the libraries sector online was three to four times a year (31%).

Figure 3.3: Most frequent level of physical and digital engagement with the libraries sector, England: 2023/24 (Base: Adults who physically or digitally engaged with libraries)

Figure 3.4 shows that the most popular activities to do whilst physically engaging with libraries was ‘browsing, borrowing, and returning reading and media materials’(60%) and ‘‘Took a child to borrow, browse or return books’ (27%). This was followed by ‘Used free Wi-Fi, computer or printing facilities’ (23%) and ‘Used the library as a study space’ (19%). This was similar to the previous year (2022/23).

Figure 3.4: Activities done whilst visiting a public or mobile library in person, England: 2023/24 (Base: Adults who physically engaged with libraries)

Figure 3.5 shows that for digital engagement ‘Reserved or renewed books or paid a fine’ was the most popular (48%) activity, followed by ‘Searched online catalogues or dictionaries or made an enquiry’ or ‘Borrowed digital or online resources’, both 44%. This was similar to the previous year (2022/23).

Figure 3.5: Activities done when engaging online with the libraries sector, England: 2023/24 (Base: Adults who digitally engaged with libraries)

Who engaged with libraries ?[footnote 8]

Figure 3.6 shows that in 2023/24:

- Age: There was a lot of variation in how people of different ages physically or digitally engaged with libraries. For instance, 50–54 year old adults (19%) and 55–59 year old adults (18%) physically engaged with libraries less than all other age groups presented here (21–33%). For digital engagement, 16–19 year olds (23%) digitally engaged with libraries more than than all other age groups presented here (7–19%), whilst the adults aged 85 or older (7%) digitally engaged less than all other age groups presented here (9–23%).

- Disability Status: Non-disabled adults (26%) were more likely to physically engage with libraries than disabled adults (24%). Similarly for digital engagement, non-disabled adults (15%) were more likely to digitally engage with libraries than disabled adults (13%).

Figure 3.6: Physical and digital engagement with the libraries sector, by age and disability status, England: 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

Figure 3.7 shows that in 2023/24:

- Sex: Female adults (28%) were more likely to physically engage with libraries than male adults (22%). There was a similar pattern for digital engagement, as female adults (15%) were more likely to digitally engage with libraries than male adults (13%).

- Gender identity: Adults who reported that their gender identity was different from their sex registered at birth (31%) physically engaged with libraries more than adults whose gender identity was the same as their sex registered at birth (25%). This was a similar pattern for digital engagement, where 14% of adults whose gender identity was the same as their sex registered at birth digitally engaged with the libraries, whilst 25% of adults who reported that their gender identity was different from their sex registered at birth digitally engaged with the libraries.

- Sexual Orientation: Bisexual adults (34%) and adults in the “other” sexual orientation classification (35%) were more likely to physically engage with the arts than heterosexual or straight adults (25%) or gay or lesbian adults (24%). For digital engagement, adults in the “other” sexual orientation classification (34%) engaged more than all other sexual orientation classifications presented here. Whilst, heterosexual or straight adults (14%) digitally engaged with libraries less than all other sexual orientation classifications presented here. Bisexual adults (25%) digitally engaged with libraries more than gay or lesbian adults (17%). There were no other differences between the classifications presented here for library engagement.

Figure 3.7: Physical and digital engagement with the libraries sector, by sex[footnote 9], gender identity[footnote 10] and sexual orientation[footnote 11], England: 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

Figure 3.8 shows that:

- Religion: Non-religious adults (24%) engaged less physically with the libraries sector than adults from all other religious groups presented here (25–35%). Christian adults (25%) were less likely to physically engage with libraries than adults from all other religious groups presented here (29–35%) with the exception of non-religious adults. For digital engagement with libraries, Christian adults (13%) were less likely to engage with libraries than adults from all other religious groups presented here (14–26%). Non-religious adults (14%) were also less likely to digitally engage with libraries than all other religious groups presented here with the exception of Christian adults. Adults from the ‘any other’ religious group (34%) engaged less than all other religious groups presented here with exception of non-religious adults or Christian adults. There were no other differences between the classifications presented here for library engagement.

- Ethnicity: There was a lot of variation in how adults from different ethnic groups engaged with libraries either physically or digitally. For instance, white British adults[footnote 17] were less likely to physically (23%) or digitally (12%) engage with libraries than all other ethnic groups presented here.

Figure 3.8: Physical and digital engagement with the libraries sector, by religion and ethnicity, England: 2023/24.

| Bar label | Ethnicity | Bar label | Ethnicity | Bar label | Ethnicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Bangladeshi | G | Caribbean | M | Arab |

| B | Chinese | H | Any other black, African, or Caribbean background | N | Any other ethnic group |

| C | Indian | I | Mixed white and Asian | O | English, Welsh, Scottish, Northern Irish, or British |

| D | Pakistani | J | Mixed white and black African | P | Gypsy or Irish Traveller |

| E | Any other Asian background | K | Mixed white and black Caribbean | Q | Irish |

| F | African | L | Any other multi-ethnic background | R | Any other white background |

Figure 3.9 shows that:

-

Socio-economic classification: There was some variation in both physical and digital engagement in the libraries for adults of different socio-economic classifications. For example, for both physical and digital engagement with libraries, adults from the higher managerial, administrative and professional occupations classification (28% and 16%) engaged with libraries more than adults from all other socio-economic classifications presented here, whilst adults from routine and manual occupations (19% and 10%) engaged less with libraries than all from all other socio-economic classifications presented here.

-

Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD): There was some variation in both physical and digital engagement with libraries for adults in different deprivation deciles. For example, adults from the highest decile (the least deprived) (29%) engaged the most with libraries physically compared to adults from all other deciles (23–26%). For digital engagement, adults from the highest decile (the least deprived) (16%) engaged slightly more digitally with libraries compared to adults from all other deciles (13-15%), with the exception of adults from the 3rd or 4th decile (both 15%).

Figure 3.9: Physical and digital engagement with the libraries sector, by socio-economic classification[footnote 12] and Index of Multiple Deprivation[footnote 13], England: 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

| Bar label | Socio-Economic Classification |

|---|---|

| A | Higher managerial, administrative, and professional occupations |

| B | Intermediate occupations |

| C | Routine and manual occupations |

| D | Never worked and long-term unemployed |

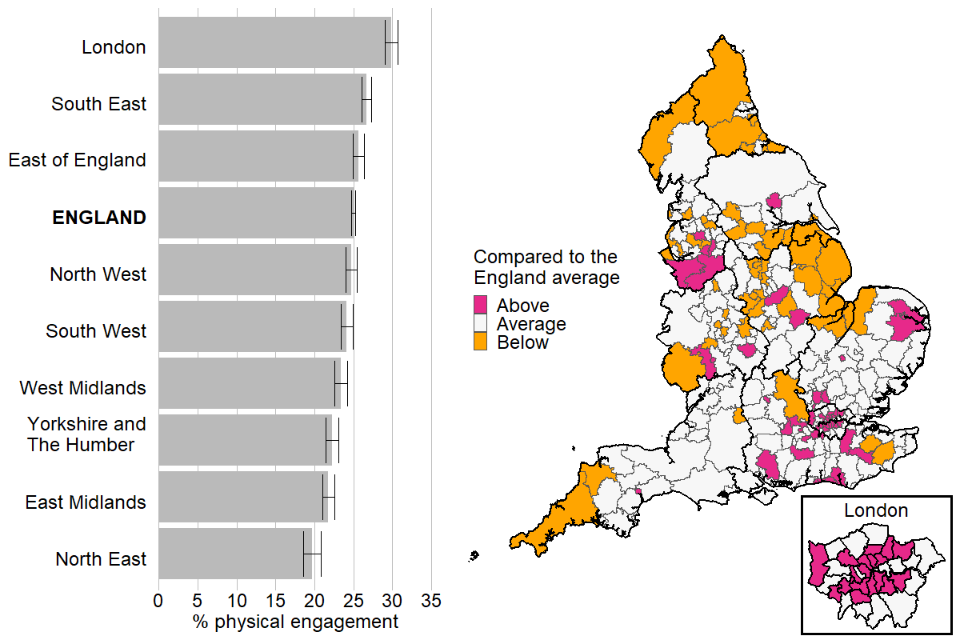

Geographical findings

Figure 3.10 shows that compared with the England average, adults in the London (30%) region physically engaged with libraries more, whilst adults in the West Midlands (23%), Yorkshire and the Humber (22%), East Midlands (22%) and the North East (20%) regions physically engaged with libraries less than the England average (25%). Of 296 LAs, 63% are not significantly different to the England average, with 17% above and 20% below, although some of these differences are small but significant. In general, the patterns of usage at the regional level are also observed at the local authority (LA) level. There are however some exceptions:

- In the South East (27%) region where physical engagement with libraries was higher than the England average, Ashford (19%), Buckinghamshire (21%) and Maidstone (18%) local authorities were lower than the average.

- In the West Midlands (23%) region where physical engagement with libraries was lower than the England average, Malvern Hills (32%), Warwick (32%) and Worcester (33%) local authorities were higher than the average.

- In the East Midlands (22%) region where physical engagement with libraries was lower than England average, Rushcliffe (35%) and Rutland (31%) local authorities were higher than the average.

- In Yorkshire and the Humber (22%) region where physical engagement with libraries was lower than the England average, York (31%) local authority was higher than the average.

Figure 3.10: Physical engagement with the libraries sector, by Local Authority[footnote 14][footnote 15], England: 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

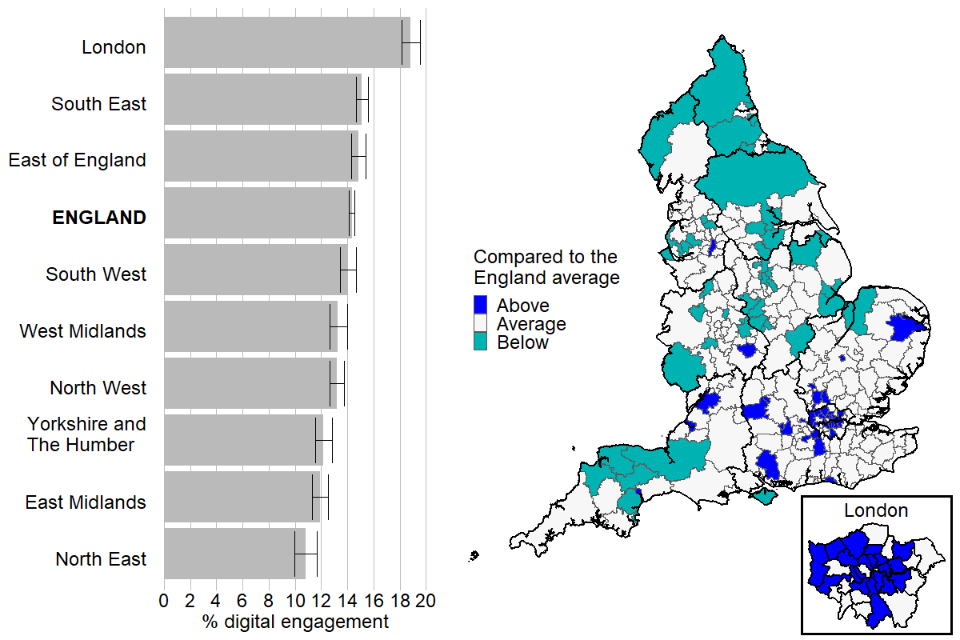

Figure 3.11 shows that similarly to physical engagement with libraries, compared with the England average, adults in London (19%) digitally engaged with libraries more, whilst adults in the South East (15%) digitally engaged with libraries slightly more than the England average (14%). Adults in the West Midlands (13%) and North West (13%) regions digitally engaged with libraries slightly less than the England average, whilst adults in Yorkshire and the Humber (12%), East Midlands (12%) and the North East (11%) regions digitally engaged with libraries less than the England average. In general, the patterns of usage at the regional areas are also observed at the local authority (LA) level. Of 296 LAs, 70% are within the England average, with 14% above and 16% below, although some of these differences are small but significant. There are however some exceptions:

- In the South East (15%) region where digital engagement with libraries was slightly higher than England’s average, the Isle of Wight (7%) local authority was lower than the average.

- In the North West (13%) region where digital engagement with libraries was lower than England’s average, Manchester (22%) local authority was above the average .

- In the West Midlands (13%) region where digital engagement with libraries was slightly lower than England’s average, Warwick (19%) local authority was above the average .

Figure 3.11: Digital engagement with the libraries sector, by Local Authority[footnote 14][footnote 15], England: 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

Barriers to engagement

Respondents who did not engage with the libraries were asked why they did not. The most common reasons given are shown in Figure 3.12 and were:

- For physical engagement – ‘I don’t need to use library services’ (33%) and ‘I’m not interested’ (27%) were the most common barriers cited for not engaging with libraries.

- For digital engagement – ‘I’m not interested’ (28%) and ‘I don’t need to use library services’ (27%) were most commonly identified as barriers to engaging with libraries.

Figure 3.12: Reasons for not physically or digitally engaging with the libraries sector, England: 2023/24 (Base: Adults who did not engage with libraries)

4. Heritage

Physical engagement with the heritage sector is defined as visiting one of a variety of places with celebrated histories, such as those connected with industrial history, or ancient monuments, or archaeological sites. Digital engagement with the heritage sector includes taking a virtual tour of any of those physical locations listed in Figure 4.3, plus viewing documents from an archive in England online, or researching local history online. The full list of qualifying heritage activities[footnote 4] we asked about are in Annex 3 and shown in Figures 4.4 and 4.6.

Note, the total heritage engagement (physical or digital) figure and figure for engaging in heritage both physically and digitally are only available for quarters 3 and 4, due to an error in the survey set-up where the physical heritage questions were asked to one subset of respondents, whilst the digital heritage questions were asked to a different subset of respondents in the prior quarters. This error was rectified for quarter 3 and quarter 4. Thus, the estimates for “physically OR digitally” and “physically AND digitally” were calculated using the quarter 3 and quarter 4 data only. Other measures of heritage engagement in either mode are based on all four quarters.

Headline findings

During May 2023 to March 2024 (2023/24): 69%

of adults reported having engaged with the heritage sector in the last 12 months[footnote 18], no change from 2022/23 (69%), as shown in Figure 4.1.

Figure 4.1: Total engagement with the heritage sector (physically or digitally)[footnote 19], England: 2022/23 – 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

Figure 4.2 shows that 66% of adults had visited a heritage site physically in the previous 12 months to being surveyed, a 1 percentage point decrease from 2022/23 (67%). The corresponding figure for digital engagement was 25%, a 7 percentage point increase from 2022/23 (18%)[footnote 20].

Figure 4.2: Physical engagement and digital engagement with the heritage sector[footnote 19], England: 2022/23 – 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

Figure 4.3 shows that of those who engaged with the heritage sector, the most frequent level[footnote 21] was three to four times a year (around 38% for physical and 36% digital).

Figure 4.3: Most frequent level of physical and digital engagement with the heritage sector, England: 2023/24 (Base: Adults who physically or digitally engaged with heritage sector from subsample of approximately a third of online respondents)

Figure 4.4 shows that the most popular heritage activities were visiting:

- Parks or garden with historic or artistic features (40%)

- A city or town with celebrated historic nature (37%)

- A historic landscape or habitat (37%)

Figure 4.4: Forms of physical engagement with the heritage sector, England: 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

Figure 4.5 shows that the top cited reason for engaging with the heritage sector physically was “To spend time with family or friends” (57%), followed by “General interest in the heritage site” (52%). Furthermore, 33% of adults reported that they engaged with heritage sites because “It was in the area”.

Figure 4.5: Reasons for visiting heritage sites, England: 2023/24 (Base: Adults who physically engaged with heritage sector from subsample of approximately a third of online respondents)

Figure 4.6 shows that the digital heritage activity that most adults engaged with was something not in the list given (75%). From the list given, “Researched your local history online” was the most popular (14%).

Figure 4.6: Forms of digital engagement with the heritage sector, England: 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

Respondents were asked how they usually paid for digital heritage content. Of those who did engage digitally with heritage, the most common response was “Access content using a log-in belonging to someone NOT in my household” (69%), followed by “Access free content” (15%)

Who engaged with the heritage sector?[footnote 8]

Figure 4.7 shows that in 2023/24:

- Age:There was a lot of variation in how people of different ages physically or digitally engaged with the heritage sector. For example, 65 to 74 year old adults (74%) physically engaged with the heritage sector more than all other age groups presented here (45–70%). Adults aged 85 or above were less engaged physically (45%) or digitally (15%) with the heritage sector compared to all other age groups presented here.

- Disability Status: Non-disabled adults (70%) were more likely to physically engage with the heritage sector than disabled adults (60%). For digital engagement with the heritage sector, there were no differences observed between adults of different disability status.

Figure 4.7: Physical and digital engagement with the heritage sector, by age and disability status, England: 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

Figure 4.8 shows that in 2023/24:

- Sex: There were no differences in the level of physical engagement with the heritage sector by sex. However, male adults (27%) digitally engaged with the heritage sector more than female adults (22%).

- Gender identity: For physical engagement with the heritage sector, there were no differences observed between adults whose gender identity was the same as their sex registered at birth and adults who reported that their gender identity was different from their sex registered at birth. However, for digital engagement, adults who reported that their gender identity was different from their sex registered at birth (30%) engaged digitally with the heritage sector more than adults whose gender identity was the same as their sex registered at birth (25%) .

- Sexual Orientation: Heterosexual or straight adults (66%) physically engaged with the heritage sector less than all other sexual orientation classifications presented here (69–73%). Similarly for digital engagement, heterosexual or straight adults (24%) physically engaged with the heritage sector less than all other sexual orientation classifications presented here (32–38%). Adults in the “other” sexual orientation classification (38%) digitally engaged more than gay or lesbian adults (32%). There were no other differences between the sexual orientation classifications presented here for engagement with the heritage sector.

Figure 4.8: Physical and digital engagement with the heritage sector, by sex[footnote 9], gender identity[footnote 10] and sexual orientation[footnote 11], England: 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

Figure 4.9 shows that:

- Religion: There was some variation in how adults from different religious groups engaged with the heritage sector. For example, Muslim adults (49%) or Sikh adults (50%) physically engaged the least with the heritage sector than all other religious groups presented here (64–78%). Whereas, Buddhist adults (76%), Jewish adults (74%) or adults from the ‘any other’ religious group classification (78%) physically engaged the most with the heritage sector compared to all other religious groups presented here (49–69%). For digital engagement, for instance, Non-religious adults (24%) digitally engaged less with the heritage sector compared to all other religious groups presented here, with the exception of Muslim adults (25%), Sikh adults (26%) or Christian adults (25%).

- Ethnicity: There was a lot of variation in how adults from different ethnic groups engaged with the heritage sector. For instance, adults from any other white background (74%) physically engaged with the heritage sector more than white British adults[footnote 17] (68%). Whereas for digital engagement, adults from the white and Asian ethnic group (32%) engaged more with heritage than white British adults[footnote 17] (24%).

Figure 4.9: Physical and digital engagement with the heritage sector, by religion and ethnicity, England: 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

| Bar label | Ethnicity | Bar label | Ethnicity | Bar label | Ethnicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Bangladeshi | G | Caribbean | M | Arab |

| B | Chinese | H | Any other black, African, or Caribbean background | N | Any other ethnic group |

| C | Indian | I | Mixed white and Asian | O | English, Welsh, Scottish, Northern Irish, or British |

| D | Pakistani | J | Mixed white and black African | P | Gypsy or Irish Traveller |

| E | Any other Asian background | K | Mixed white and black Caribbean | Q | Irish |

| F | African | L | Any other multi-ethnic background | R | Any other white background |

Figure 4.10 shows that:

- Socio-economic classification: There was some variation in both physical and digital engagement in the heritage sector for adults of different socio-economic classifications. For example, adults from the higher managerial, administrative and professional occupations classification engaged physically (76%) and digitally (29%) with the heritage sector more than adults from all other socio-economic classifications presented here. Adults from the never worked and long-term unemployed classification engaged (47%) less physically with the heritage sector than adults from all other socio-economic classifications presented here (57–76%). Adults from the never worked and long-term unemployed classification engaged digitally (23%) slightly more with the heritage sector than adults from the intermediate occupations classification (22%) or adults from routine and manual occupations classifications (21%).

- Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD): There was some variation in how adults from different deprivation deciles physically engaged with the heritage sector. Generally, as deprivation decreased, physical engagement in the heritage sector increased, with adults from the lowest decile (the most deprived) engaging physically with the heritage sector the least (51%) compared to adults from all other deciles presented here (55–76%). The highest three deciles, 8th, 9th and 10th decile engaged more (73%,74% and 76% respectively) than all other deciles presented here (51–71%). For digital engagement, the most deprived decile (22%) engaged less than adults from all deciles except for the second and seventh decile (24%).

Figure 4.10: Physical and digital engagement with the heritage sector, by socio-economic classification[footnote 12] and Index of Multiple Deprivation[footnote 13], England: 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

| Bar label | Socio-Economic Classification |

|---|---|

| A | Higher managerial, administrative, and professional occupations |

| B | Intermediate occupations |

| C | Routine and manual occupations |

| D | Never worked and long-term unemployed |

Geographical findings

Figure 4.11 shows that, compared with the England average, adults in the South East (70%) and South West (72%) regions physically engaged with heritage more, whilst adults in the West Midlands (62%) and North West (63%) regions physically engaged with heritage less than the England average (66%). Of 296 LAs, 66% are not significantly different to the England average, with 18% above and 16% below, although some of these differences are small but significant. In general, the patterns of usage at the regional level are also observed at the local authority (LA) level. However, there are a few exceptions:

- In the South East (70%) region where physical engagement with heritage was higher than the England average, Dartford (58%), Milton Keynes (60%) and Slough (54%) local authorities were lower than the average.

- In the West Midlands (62%) region where physical engagement with heritage was lower than the England average, Shropshire (78%), Stratford-on-Avon (78%), Warwick (76%) and Wychavon (74%) local authorities were higher than the average.

- In the North West (63%) region where physical engagement with heritage was lower than the England average, Cheshire East (73%) and Westmorland and Furness (72%) local authorities were higher than the average.

Figure 4.11: Physical engagement with the heritage sector, by Local Authority[footnote 14][footnote 15]: 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

Figure 4.12 shows that for digital engagement with heritage, adults in London (26%) engaged slightly more than the England average (25%), whilst adults in Yorkshire and the Humber (22%) and the East Midlands (23%) regions engaged less. Of 296 LAs, 91% are not significantly different to the England average, with 4% above and 5% below, although some of these differences are small but significant. In general, the patterns of usage at the regional level are also observed at the local authority (LA) level. However, there are a few exceptions:

-

In London (26%) where digital engagement with heritage was slightly higher than the England average, Redbridge (18%) local authority engaged less.

-

In the East Midlands (23%) where digital engagement with heritage was lower than the England average, High Peak (33%) local authority engaged more.

Figure 4.12: Digital engagement with the heritage sector, by Local Authority[footnote 14][footnote 15], England: 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

Barriers to engagement

Respondents who did not engage with the heritage sector were asked why they did not. The most common reasons given are shown in Figure 4.13 and were:

- For physical engagement, ‘No reason in particular’ (32%) and ‘I’m not interested’ (25%) were the most common barriers cited for not engaging with the heritage sector.

- For digital engagement, similarly, ‘I’m not interested’ (40%) and ‘No reason in particular’ (33%) were most commonly identified as barriers to engaging with the heritage sector.

Figure 4.13: Reasons for not physically or digitally engaging with the heritage sector, England: 2023/24 (Base: Adults who did not engage with heritage sector)

5. Museums and Cultural Property

For physical engagement, respondents were asked about their visits to museums and galleries in the 12 months prior to completing the survey. Digital engagement with museums and galleries includes having taken a virtual tour of a museum or gallery in England or researching items from a museums and gallery collection in England online. The full list of qualifying digital museum activities we asked about are in Annex 3 and shown in Figure 5.5.

Headline findings

During May 2023 to March 2024 (2023/24), nearly half of adults 46% engaged with museums and galleries in the last 12 months, a 11 percentage point increase from 2022/23 (35%).

Figure 5.1 shows that 43% of adults engaged with museums and galleries physically in the previous 12 months to being surveyed, a 10 percentage point increase from 2022/23 (33%). The corresponding figure for digital engagement was 13%, a 4 percentage point increase from 2022/23 (9%).

Figure 5.1: Engagement with museums and galleries , England: 2022/23 – 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

Figure 5.2 shows that of the 46% of adults who engaged with museums and galleries, 33% of adults engaged exclusively physically, whilst 10% engaged both physically and digitally and only 3% engaged exclusively digitally.

Figure 5.2: Physical and digital engagement with museums and galleries, England: 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

Figure 5.3 shows that of those who physically engaged with museums and galleries, the most frequent level[footnote 22] at which adults visited museums and galleries was at least three to fours times a year (33%). Similarly, of those who digitally engaged with the museums and galleries, the most frequent level at which adults engaged online was also three to four times a year (33%).

Figure 5.3: Frequency of physical and digital engagement with museums and galleries, England: 2023/24 (Base: Adults who physically or digitally engaged with museums and galleries)

Figure 5.4 shows that the most popular reason for visiting museums and galleries was “General interest in the subject of the museum or collection” (65%), followed by “To spend time with family or friends” (54%).

Figure 5.4: Reasons for visiting museums and galleries, England: 2023/24 (Base: Adults who physically engaged with museums and galleries)

Figure 5.5 shows that the majority of adults did not engage with the digital museums and galleries activities listed in the survey (87%). From the options listed in the survey, “Researched items from a museum or gallery collection in England online” (7%) and “Engaged with multimedia content from Museums and galleries in England” (6%) were the next most popular activity undertaken .

Figure 5.5: Forms of digital engagement with museums and galleries, England: 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

The survey also asked respondents if they had taken part in metal detecting or mudlarking in the last 12 months. The majority of respondents did none of these activities (98%), however,

- 1% of adults reported that they had taken part in mudlarking

- 1% of adults reported they had taken part in metal detecting to search for historic artefacts. Of these respondents,

- 67% reported they did this as ‘As an individual or part of a social group’

- 21% reported they did this as ‘Part of a metal-detecting club’

- 14% reported they did this as ‘As part of an organised archaeological survey in a volunteer role’

Who engaged with museums and galleries?[footnote 8]

Figure 5.6 shows that in 2023/24:

- Age: There were some variations in engagement with museums and galleries between adults of different age groups. For instance, adults aged 85 and over were the least likely to visit museums and galleries (18%) or engage with museums and galleries digitally (9%) compared to adults from all other age groups presented here. There were other variations, for instance, 16–19 year old adults (34%) were less likely to visit a museum than adults from all other age groups presented here, with the exception of adults aged 80 or over. Whereas 16–19 year old adults (17%) were more likely to digitally engage with museums than adults from all other age groups presented here, with the exception of 70–74 year old adults.

- Disability Status: Non-disabled adults (46%) were more likely to visit museums and galleries than disabled adults (37%). There were no differences in digital engagement with museums and galleries between disability statuses.

Figure 5.6: Physical and digital engagement with the museums and galleries sector, by age and disability status, England: 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

Figure 5.7 shows that in 2023/24:

- Sex: Female adults (44%) were more likely to visit museums and galleries than male adults (42%). However, male adults (14%) were slightly more likely to digitally engage with museums and galleries than female adults (13%).

- Gender identity: For physical engagement with museums and galleries, there were no differences observed between adults whose gender identity was the same as their sex registered at birth and adults who reported that their gender identity was different from their sex registered at birth. However, for digital engagement, adults who reported that their gender identity was different from their sex registered at birth (22%) digitally engaged with the museums and galleries more than adults whose gender identity was the same as their sex registered at birth (13%).

- Sexual Orientation: Heterosexual or straight adults physically (44%) or digitally (13%) engaged with the museums and galleries less than all other sexual orientation classifications presented here. Bisexual adults (57%) or gay or lesbian adults (56%) engaged more physically with museums and galleries than adults in the “other” sexual orientation (50%). Adults in the “other” sexual orientation (30%) digitally engaged with museums and galleries more than bisexual adults (24%) or gay or lesbian adults (18%). Bisexual adults (24%) digitally engaged more than gay or lesbian adults (18%). There were no other differences in engagement with museums and galleries between the sexual orientation classifications presented here.

Figure 5.7: Physical and digital engagement with the museums and galleries sector, by sex[footnote 9], gender identity[footnote 10] and sexual orientation[footnote 11], England: 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

Figure 5.8 shows that:

- Religion: There was some variation in museums and galleries engagement for adults of different religious groups. For example, Muslim adults (31%) or Sikh adults (29%) were less likely to visit museums and galleries than adults from any of the other religious groups presented here (41–57%). Christian adults (13%) or non-religious adults (13%) were less likely to digitally engage in museums and galleries than adults from any of the other religious groups presented here (17–24%).

- Ethnicity: There was a lot of variation in physical engagement with museums and galleries for adults of different ethnic groups. For example, adults from the Chinese ethnic group (67%) were more likely to visit museums and galleries than adults from all other ethnic groups presented here, with the exception of adults in the “any other” ethnic group (62%) . For digital engagement, white British adults[footnote 17] (12%) engaged the least digitally with museums and galleries than adults from all other ethnic groups presented here (15–40%), with the exception of adults from the black Caribbean ethnic group (14%) and the mixed white and black Caribbean ethnic group (15%).

Figure 5.8: Physical and digital engagement with museums and galleries, by religion and ethnicity, England: 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

| Bar label | Ethnicity | Bar label | Ethnicity | Bar label | Ethnicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Bangladeshi | G | Caribbean | M | Arab |

| B | Chinese | H | Any other black, African, or Caribbean background | N | Any other ethnic group |

| C | Indian | I | Mixed white and Asian | O | English, Welsh, Scottish, Northern Irish, or British |

| D | Pakistani | J | Mixed white and black African | P | Gypsy or Irish Traveller |

| E | Any other Asian background | K | Mixed white and black Caribbean | Q | Irish |

| F | African | L | Any other multi-ethnic background | R | Any other white background |

Figure 5.9 shows that:

- Socio-economic classification: There was some variation in both physical and digital engagement in the museums and galleries for adults of different socio-economic classifications. Adults from the higher managerial, administrative and professional occupations classification engaged physically (54%) and digitally (15%) with museums and galleries more than adults from all other socio-economic classifications presented here. Adults from the never worked and long-term unemployed classification engaged physically (25%) less with museums and galleries than adults from all other socio-economic classifications presented here (31–54%). Adults from the never worked and long-term unemployed classification engaged digitally (15%) more with museums and galleries than adults from the intermediate occupations classification (11%) or adults from routine and manual occupations classifications (10%).

- Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD): There were some variations in museum and gallery engagement between adults from different deprivation deciles. For instance, adults from the lowest decile (most deprived) (31%) were less likely to visit museums and galleries than adults from all other deciles presented here (36–51%). Whereas, adults from the highest decile (the least deprived) (51%) were more likely to visit museums and galleries than adults from all other deciles presented here (31–48%). There were no differences observed between adults digitally engaging with museums in different deprivation deciles.

Figure 5.9: Physical and digital engagement with the museums and galleries, by socio-economic classification[footnote 12] and Index of Multiple Deprivation[footnote 13], England: 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

| Bar label | Socio-Economic Classification |

|---|---|

| A | Higher managerial, administrative, and professional occupations |

| B | Intermediate occupations |

| C | Routine and manual occupations |

| D | Never worked and long-term unemployed |

Geographical findings

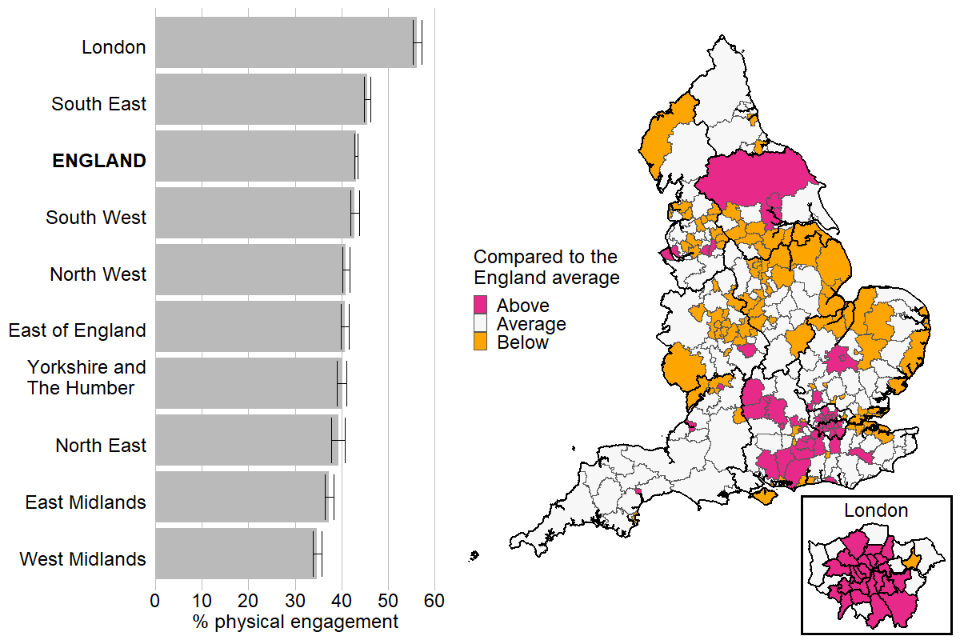

Figure 5.10 shows that compared with the England average (43%), adults in London (56%) and South East (46%) regions visited museums and galleries more, whilst adults in the North West (41%), East of England (41%), Yorkshire and the Humber (40%), North East (39%), East Midlands (37%) and West Midlands (35%) regions physically engaged with museums and galleries less than the England average. Of 296 LAs, 50% are not significantly different to the England average, with 19% above and 31% below, although some of these differences are small but significant. In general, the patterns of usage at the regional level are also observed at the local authority (LA) level. However, there are some exceptions:

- In the London (56%) region where physical engagement with museums and galleries was higher than the England average, Barking and Dagenham (37%) local authority was lower than the average.

- In the South East (46%) region where physical engagement was higher than the England average, the following LA’s were lower than the average: Arun (37%), Bracknell Forest (37%), Crawley (37%), Dartford (36%), Gosport (37%), Gravesham (29%), Havant (34%), Isle of Wight (34%), Medway (37%), Rushmoor (37%), Slough (35%) and Swale (36%).

- In the East of England (41%) region where physical engagement with museums and galleries was lower than the England average, Cambridge (74%), South Cambridgeshire (59%), St Albans (61%) and Three Rivers (49%) local authorities were higher than average.

- In the West Midlands (35%) region where physical engagement with museums and galleries was lower than the England average, Warwick (53%) was higher than the average.

- In the Yorkshire and Humber region (40%), where physical engagement with museums and galleries was lower than the England average, York (59%) and North Yorkshire (46%) local authority was higher than the average.

- In the North West region (41%), where physical engagement with museums and galleries was lower than the England average, Liverpool (55%), Manchester (50%), Trafford (51%), and Wirral (51%) local authorities were higher than average.

Figure 5.10: Physical engagement with museums and galleries, by Local Authority[footnote 14][footnote 15], England: 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

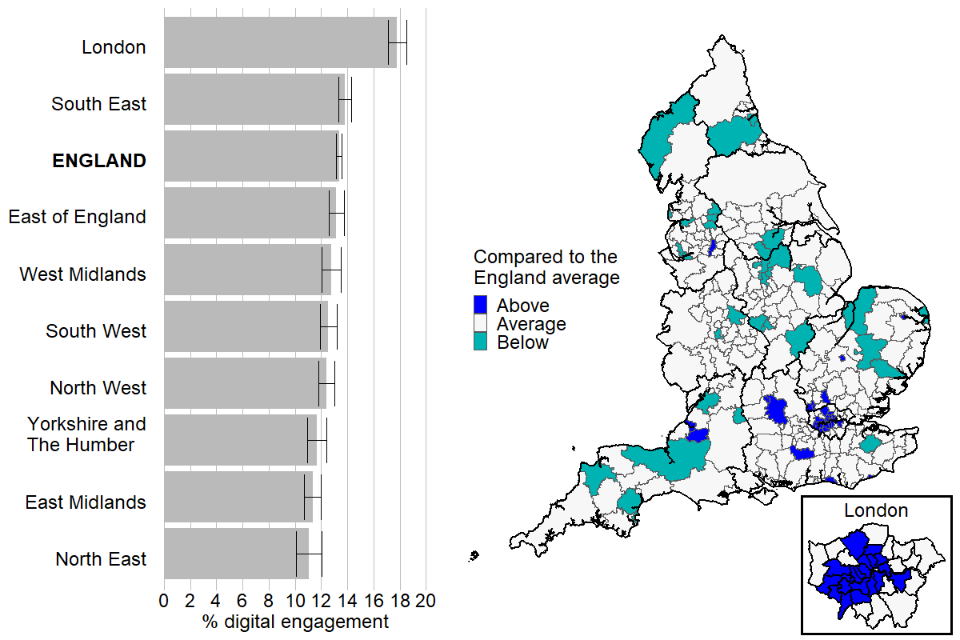

Figure 5.11 shows that, similarly to physical engagement with museums and galleries, compared with the England average (13%), adults in London (18%) region digitally engaged with museums and galleries more, whilst adults in the South West (13%), North West (12%), Yorkshire and the Humber (12%), regions digitally engaged with museums and galleries slightly less and adults in East Midlands (11%) and North East (11%) regions digitally engaged with museums and galleries less than the England average. Of 296 LAs, 78% are not significantly different to the England average, with 10% above and 11% below, although some of these differences are small but significant. In general, the patterns of usage at the regional level are also observed at the local authority (LA) level.However, there are a few exceptions:

- In the South West (13%) and North West (12%) regions digital engagement with museums and galleries was slightly lower than the England average, however, Bristol (17%) and City of Manchester (18%) local authorities were higher than the average.

Figure 5.11: Digital engagement with museums and galleries, by Local Authority[footnote 14][footnote 15], England: 2023/24 (Base: All adults)

Barriers to engagement

Respondents who did not engage with museums and galleries were asked why they did not. The most common reasons given are shown in Figure 5.12 and were:

- For physical engagement, ‘I’m not interested’ (30%) and ‘No reason in particular’ (27%) were the most common barriers cited for not engaging with museums and galleries.

- For digital engagement – similarly ‘I’m not interested’’ (40%) and ‘No reason in particular’ (31%) were most commonly identified as barriers to engaging with museums and galleries.

Figure 5.12: Reasons for not physically or digitally engaging with museums and galleries, England: 2023/24 (Base: Adults who did not engage with museums and galleries)

6. Live Sports & Gambling

Respondents were asked information about attendance at live sports in the last six months (that is, covering the period October 2022 to March 2024). Note that questions related to gambling refers to the last 12 months (that is, covering the period May 2022 to March 2024).

Headline findings

31%of adults reported that they had watched live sports in person in the last six months, a 9 percentage point increase from 2022/23 (22%), as shown in Figure 6.1.

Nearly three quarters (73%) of respondents watched live sports on TV in the last twelve months, a 14 percentage point increase from 2022/23 (59%).

Figure 6.1: Attendance in person and watching on TV of live sporting events, England: 2022/23 – 2023/24 (Base: Adults in subsample of approximately a third of online respondents)

Of the 31% of adults who watched any live sports in person in the last 6 months, Figure 6.2 shows the order of popularity was:

- Men’s football (60%)

- Rugby (20%)

- Some other type of sport (17%) (any sport not listed in Figure 6.2)[footnote 23]

- Cricket (16%)

These were the most popular sports in the previous year too (excluding Men’s football[footnote 24]).

Of the 73% of adults who watched any live sports on TV, Figure 6.2 shows the order of popularity was:

- Men’s Football (53%)

- Women’s football (34%)

- Tennis (30%)

Bearing in mind that more people watched any sports on TV than in person (73% versus 31%), Figure 6.2 shows the popularity of the different sports that were watched as a proportion of adults who said yes to watching at least one live sport or yes to watching at least one sport on TV.

Figure 6.2: Ranking the popularity of live sporting events watched in person in the previous 6 months, and watched on TV in the previous 12 months, England: 2023/24. (Base: Adults who watched at least one live sporting event in person / Adults who watched at least one live sporting event on TV)

57% of respondents who watched live sports on TV said all of these events were professional sports where the participants were being paid, whereas 13% said most of them were. 14% of respondents said none of the events were professional sports where the participants were being paid.

Around 25% of adults who attended live sports (of any type) in person in the previous 6 months placed a bet. This compares to 17% of adults who watched live sports on TV who placed a bet while watching. Figure 6.3 shows that of the adults who attended live sports in person and placed bets:

- 38% reported to do so very rarely,

- 38% said some of the time,

- 15% said most of the time.

Whereas, of the adults who watched live sports on TV and placed bets:

- 49% did so very rarely,

- 34% placed a bet some of the time,

- 11% placed a bet most of the time.

Figure 6.3: Engagement in betting during watching live sports in person and on TV, by frequency, England: 2023/24. (Base: Adults who watched at least one live sporting event in person and placed a bet / Adults who watched at least one live sporting event on TV and placed a bet)

Who watched live sports?[footnote 8]

Figure 6.4 shows:

- Age: There were some variations in watching live sports between adults of different age groups. For instance, adults aged 85 and over were the least likely to watch live sports (13%) compared to adults from all other age groups presented here, whilst adults aged 16–19 (35%) and 45–49 (34%) were more likely to watch live sports than adults aged 70 and over (13–29%).

- Disability Status: Non-disabled adults (34%) were more likely to have attended live sporting events in person than disabled adults (23%).

Figure 6.4: Attendance of live sporting events in the previous 6 months, by age and disability status, England: 2023/24. (Base: Adults in subsample of approximately a third of online respondents)

Figure 6.5 shows:

- Sex: Male adults (40%) were more likely to have attended live sporting events than female adults (22%).

- Gender identity: Adults whose gender identity was the same as their sex registered at birth (31%) were more likely to have attended live sporting events than adults who reported that their gender identity was different from their sex registered at birth (24%).

- Sexual Orientation: Heterosexual or straight adults (32%) were more likely to attend live sporting events than adults of other sexual orientations (15%–23%).

Figure 6.5: Attendance of live sporting events in the previous 6 months, by sex[footnote 9], gender identity[footnote 10] and sexual orientation[footnote 11], England: 2023/24. (Base: Adults in subsample of approximately a third of online respondents)

Figure 6.6 shows that:

- Religion: Non-religious adults (32%) were more likely to attend live sporting events compared to Buddhist adults (17%), Muslim adults (21%), or adults in the “other” religious classification (22%). Jewish adults (35%) were more likely to attend live sporting events than Muslim adults (21%) or Buddhist adults (17%). There were no other differences in the attendance of live sporting events between the religious groups presented here.

- Ethnicity: There was some variation in live sport attendance for adults of different ethnic groups. For example, adults from the white British adults[footnote 17] (33%) were more likely to attend live sporting events than adults from the “any other white background” ethnic group (22%).

Figure 6.6:Attendance of live sporting events in the previous 6 months, by religion and ethnicity, England: 2023/24. (Base: Adults in subsample of approximately a third of online respondents)

Note: “Any other black, African, or Caribbean background” (H) ethnicity group is not shown due to the data being suppressed because fewer than 30 respondents selected this option.

| Bar label | Ethnicity | Bar label | Ethnicity | Bar label | Ethnicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Bangladeshi | G | Caribbean | M | Arab |

| B | Chinese | H | Any other black, African, or Caribbean background | N | Any other ethnic group |

| C | Indian | I | Mixed white and Asian | O | English, Welsh, Scottish, Northern Irish, or British |

| D | Pakistani | J | Mixed white and black African | P | Gypsy or Irish Traveller |

| E | Any other Asian background | K | Mixed white and black Caribbean | Q | Irish |

| F | African | L | Any other multi-ethnic background | R | Any other white background |

Figure 6.7 shows that:

- Socio-economic classification: Adults from the higher managerial, administrative and professional occupations classification (34%) were more likely to attend live sporting events compared to adults from all other classifications presented here (20–30%). Adults in the never worked or long-term unemployed classification (20%) were less likely to attend live sporting events compared to all the other classifications presented here (29–34%).

- Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD): There was some variation in live sporting event attendance for adults in different deciles. Adults from the highest two deciles (least deprived) were more likely to attend live sporting events (37%) compared to adults from the lowest seven deciles (24–31%). Adults from the lowest two deciles (most deprived) were less likely to attend live sporting events compared to adults from the remainder of the deciles (highest eight) (28–37%).

Figure 6.7: Attendance of live sporting events in the previous 6 months, by socio-economic classification[footnote 12] and Index of Multiple Deprivation[footnote 13], England: 2023/24 (Base: Adults in subsample of approximately a third of online respondents)

| Bar label | Socio-Economic Classification |

|---|---|

| A | Higher managerial, administrative, and professional occupations |

| B | Intermediate occupations |

| C | Routine and manual occupations |

| D | Never worked and long-term unemployed |

Geographical findings

Adults from the North West (33%) were the only region that was more likely to attend live sporting events than the average for England (31%).

Figure 6.8 shows that adults from Merseyside (35%) were the only ITL2 region more likely to attend live sporting events than the average for England as a whole (31%). Adults from the West Midlands (26%) and Outer London – East and North East (24%) were the only ITL2 regions that were less likely to attend live sporting events than the England average.

Figure 6.8:Attendance of live sporting events in the previous 6 months, by ITL2 region (county), England: 2023/24 (Base: Adults in subsample of approximately a third of online respondents)

Barriers to engagement

Respondents were asked reasons why they had not attended live sporting events. The most common reasons given are shown in Figure 6.9 and were:

- ‘I’m not interested’ (47%)

- ‘I cannot afford it’ (19%)

- ‘No reason in particular’ (17%)

Figure 6.9: Reasons for not attending live sport, England: 2023/24. (Base: Adults who had not attended any live sporting events in person)

7. Domestic Tourism

Adults in England were asked about any domestic holidays (that is, holidays in England) they took in the last 12 months. These questions were asked to a subsample of approximately a third of online respondents, so the results may be affected due to only respondents who are already using the internet responding to these questions.

Headline findings

During May 2023 to March 2024 (2023/24), over 3 in 5 adults (64%) took a holiday in England in the previous 12 months to being surveyed, a 3 percentage point increase from 2022/23 (60%), as shown in Figure 7.1.

Figure 7.1: Engagement in the domestic tourism sector, England: 2022/23 – 2023/24 (Base: Adults in subsample of approximately a third of online respondents)

Of these who took a holiday in the England:

- A third stayed 1 to 2 nights (35%).

- Almost half spent 3 to 6 nights (46%).

- Nearly a fifth stayed 7 to 10 nights (15%).

- Only 4% stayed more than 10 nights.

Figure 7.2: Percentage of adults who took a holiday in England in the previous 12 months, by length of stay, England: 2023/24. (Base: Adults who took a holiday in England)

Figure 7.3 shows that nearly a third (30%) of adults who took a holiday in England stayed at a traditional coastal or seaside town, whilst 28% stayed in the countryside or in a village and a quarter (25%) stayed in a city or large town.

Figure 7.3: Percentage of adults who took a holiday in England in the previous 12 months, by location type, England: 2023/24. (Base: Adults who took a holiday in England)

Of those who took a holiday in England, 45% said they visited museums, galleries, heritage or cultural sites or events while they were away, an increase of 2 percentage points from 2022/23 (43%).

Who engaged with the domestic tourism sector?[footnote 8]

Figure 7.4 shows:

- Age: Adults aged 85 or over (39%) were less likely to take a holiday in England compared to adults from all other age groups presented here. There were also other variations, for instance 70–74 year old adults (70%) were more likely to take a holiday in England than 16–19 year old adults, 20–24 year old adults, and 80–84 year old adults (56–59%).

- Disability Status: Non-disabled adults (68%) were more likely to take a holiday in England than disabled adults (57%).

Figure 7.4: Engagement with the domestic tourism sector, by age and disability status, England: 2023/24. (Base: Adults in subsample of approximately a third of online respondents)

Figure 7.5 shows that:

- Sex: Female adults (65%) were more likely to take a holiday in England than male adults (63%).

- Gender identity: Adults whose gender identity was the same as their sex registered at birth (64%) were more likely to take a holiday in England than adults who reported that their gender identity was different from their sex registered at birth (59%).

- Sexual Orientation: Adults in the “other sexual orientation” classification (53%) were less likely to take a holiday in England than all other sexual orientation classifications presented here (65%). There were no other differences in domestic tourism between the sexual orientation classifications presented here.

Figure 7.5: Engagement with the domestic tourism sector, by sex[footnote 9], gender identity[footnote 10] and sexual orientation[footnote 11], England: 2023/24. (Base: Adults in subsample of approximately a third of online respondents)

Figure 7.6 shows that:

- Religion: There was some variation in domestic tourism for adults from different religious groups. For example, Muslim adults (38%) were less likely to take a domestic holiday in England than adults from all other religious groups presented here (52–67%). Non-religious adults (66%) were more likely to take a domestic holiday in England than adults from all other religious groups presented here, with the exception of Christian adults (67%), and Jewish adults (65%).

- Ethnicity: There was a lot of variation in domestic tourism for adults from different ethnic groups. For example, white British adults[footnote 17] (68%) were more likely to take a holiday in England compared to adults from most other ethnic groups, with the exceptions of adults in the Chinese, any other Asian Background, Mixed white and Asian, Any other multi-ethnic background, any other ethnic group, and Irish ethnic groups.

Figure 7.6: Engagement with the domestic tourism sector, by religion and ethnicity, England: 2023/24. (Base: Adults in subsample of approximately a third of online respondents)

Note: “Any other black, African, or Caribbean background” (H) ethnicity group is not shown due to the data being suppressed because fewer than 30 respondents selected this option.

| Bar label | Ethnicity | Bar label | Ethnicity | Bar label | Ethnicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Bangladeshi | G | Caribbean | M | Arab |

| B | Chinese | H | Any other black, African, or Caribbean background | N | Any other ethnic group |

| C | Indian | I | Mixed white and Asian | O | English, Welsh, Scottish, Northern Irish, or British |

| D | Pakistani | J | Mixed white and black African | P | Gypsy or Irish Traveller |

| E | Any other Asian background | K | Mixed white and black Caribbean | Q | Irish |

| F | African | L | Any other multi-ethnic background | R | Any other white background |

Figure 7.7 shows that:

- Socio-economic classification: Adults from the higher managerial, administrative and professional occupations classification (72%) were more likely to take a domestic holiday than adults from all other classifications presented here. Adults from the never worked and long-term unemployed classification (42%) were less likely to take a domestic holiday than adults from all other socio-economic classifications presented here (58–72%) . Adults from the intermediate occupations classification (65%) were more likely to take a domestic holiday than adults from the routine or manual occupations classification (58%).

- Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD): There was a general negative correlation between taking a domestic holiday and deprivation—as deprivation decreases the likelihood of taking a holiday in England increased. Adults from the lowest decile (the most deprived) were less likely to have taken a holiday in England last year, than those from the highest decile (the least deprived), 50% compared to 75%.

Figure 7.7: Engagement with the domestic tourism sector, by socio-economic classification[footnote 12] and Index of Multiple Deprivation[footnote 13], England: 2023/24 (Base: Adults in subsample of approximately a third of online respondents)

| Bar label | Socio-Economic Classification |

|---|---|

| A | Higher managerial, administrative, and professional occupations |

| B | Intermediate occupations |

| C | Routine and manual occupations |

| D | Never worked and long-term unemployed |

Geographical findings

Adults from the London (57%) region were less likely to take a holiday in England than the average for England as a whole (64%). Adults from the South East (66%), South West (68%), and East Midlands (69%) regions were all more likely to take a holiday in England than the average for England as a whole.

Figure 7.8 shows that there was a lot of variation in the proportion of adults from different ITL2 regions who took a holiday in England. Adults from Outer London – West and North West (58%), Outer London – East and North East (51%), Inner London – West (57%), Inner London – East (56%), Greater Manchester (57%), and West Midlands (58%) ITL2 (county) regions were less likely to take a holiday in England than adults in England as a whole. Several ITL2 regions were more likely to take a holiday in England than adults in England as a whole.

Figure 7.8: Engagement with domestic tourism, by ITL2 region (county), England: 2023/24 (Base: Adults in subsample of approximately a third of online respondents)

Barriers to engagement

Respondents were asked why they did not take a holiday in England in the previous 12 months of being surveyed. The most common reasons given are shown in Figure 7.9 and were:

- ‘I cannot afford it’ (38%)

- ‘I went abroad rather than taking a holiday in England’ (24%)

- ‘No reason in particular’ (19%)

Figure 7.9: Reasons for not taking a holiday in England, England: 2023/24. (Base: Adults who did not take a holiday in England)

8. Coronation of His Majesty The King

Respondents were asked for their awareness of the Coronation of His Majesty The King. These questions were asked to a subsample of approximately a third of online respondents, so the results may be affected due to only respondents who are already using the internet responding to these questions.

Headline findings

During May 2023 to March 2024 (2023/24): 89% of adults were aware of the Coronation of His Majesty The King.

Of those adults who were aware of the Coronation of His Majesty The King, around half of adults actually participated in the event (49%)[footnote 25]. Of these respondents who participated in the event, Figure 8.1 shows that:

-

88% followed coverage on TV or radio (including watching the event and/or news about the event).

-

26% followed this event on social media.

-

16% attended a local event

Figure 8.1: Participation in the Coronation of His Majesty The King events, England: 2023/24 (Base: Adults aware of the event)

Who is aware of the Coronation of His Majesty The King?[footnote 8]

Figure 8.2 shows that in 2023/24:

- Age: Adults aged 24 and below (77–78%) were less likely to be aware of the Coronation of His Majesty The King compared to adults from all other age groups presented here. There were also other variations; for instance, 75–79 year old adults (98%) were more likely to be aware of the event than all other age groups, with the exception of adults aged 70–74 (97%), 80–84 (97%) and 85 or over (96%).

- Disability Status: Disabled adults (91%) were slightly more aware of the Coronation of His Majesty The King than non-disabled adults (90%).

Figure 8.2: Awareness of the Coronation of His Majesty The King, by age and disability status, England: 2023/24. (Base: Adults in subsample of approximately a third of online respondents)

Figure 8.3 shows that in 2023/24:

- Sex: Female adults (90%) were slightly more aware of the Coronation of His Majesty The King than male adults (89%).

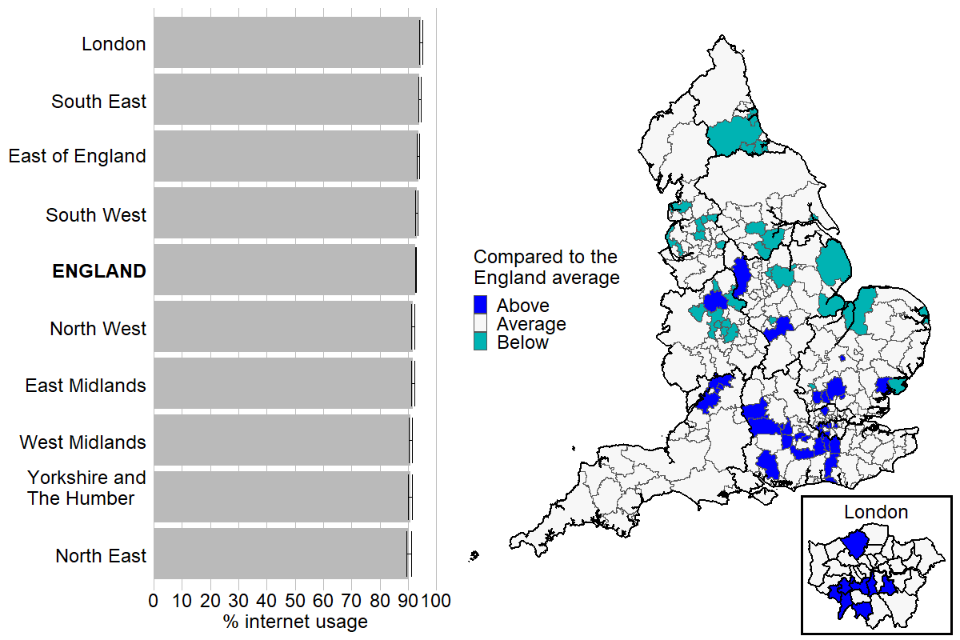

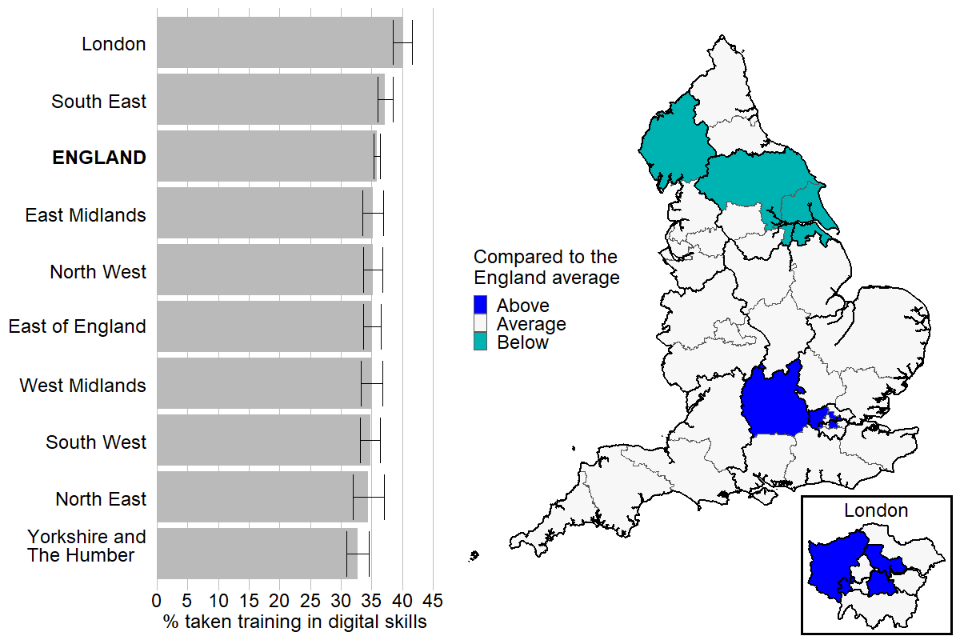

- Gender identity: Adults whose gender identity was the same as their sex registered at birth (90%) were more aware of the Coronation of His Majesty The King than adults who reported that their gender identity was different from their sex registered at birth (80%).