Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects: Advice on Preparing Applications for Linear Projects

This advice is for applications for Development Consent Orders (DCO) for linear Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects (NSIP). It is for applicants, all interested parties (IP) and persons with rights over land (affected persons (AP)).

Applies to England and Wales

The government has published guidance about national infrastructure planning which applicants and others should read. See the National Infrastructure Planning Guidance Portal. The guidance should be read alongside the Planning Act 2008 (the Planning Act).

This advice is non-statutory. However, the Planning Inspectorate’s (the Inspectorate) advice about running the infrastructure planning regime and matters of process is drawn from good practice and applicants and others should follow our recommendations. It is intended to complement the legislation, regulations and guidance issued by government and is produced under section 51 of the Planning Act.

The Planning Act provides a definition for NSIPs and sets the parameters which make a project an NSIP (sections 14 to 30). In England, development consent can be granted for both the NSIP and associated development (section 115), which may also be linear in nature. The Wales Act 2017 amended section 115 of the Planning Act and allows for certain types of associated development in connection with NSIPs located in Wales. This advice applies equally to section 35 directed projects of national significance and covers the onshore elements of offshore NSIPs.

National Policy Statements (NPS) form the basis for decision-making for most linear projects. The relevant ones are:

-

Overarching NPS for energy (NPS EN-1)

-

NPS for natural gas electricity generating infrastructure (NPS EN-2)

-

NPS for natural gas supply infrastructure and gas and oil pipelines (NPS EN-4)

-

NPS for electricity networks infrastructure (NPS EN-5)

-

National Networks NPS (NNNPS)

-

NPS for Water Resources Infrastructure

Focus of advice for linear projects

The focus of this advice is for electric lines (as defined in the Planning Act, section 16), gas transporter and other pipelines (sections 20 and 21), the transfer of water resources (section 28) and for onshore transmission works included as associated development to offshore wind generating stations.

Much of the advice is also applicable to roads and railways. This advice page will be updated as different project types appear.

In all cases the Inspectorate’s Good Design Advice Pages will also be relevant. (This advice references guidance and advice from other bodies, including the National Infrastructure Commission (NIC) and Planning Policy Wales, which is not repeated here). The Inspectorate will prepare advice on general design and practice issues in due course.

ExAs will be aiming to make recommendations to Secretaries of State with no, or as few unresolved matters as possible, in line with government statements in decisions on other NSIPs. The overall aim of this advice is therefore to help all parties recognise what information and engagement processes during the pre-application stage will facilitate the smooth running of examination, recommendation and decision stages for linear NSIPs.

To this aim, this advice on applications for linear projects is to provide examples and good practice to assist:

- applicants in preparing applications which include information that might otherwise be requested during examination

- IPs (including local authorities, statutory consultees and local communities) in understanding the areas where pre-application engagement and agreement is needed

- persons with rights over land, called affected persons (APs), including Statutory Undertakers (SU) regarding engagement and the timeliness of reaching agreement

By their nature linear projects will interact with larger numbers of IPs and APs than a single-site piece of infrastructure. The geography means that they will also pass through different environments and administrative boundaries and affect different communities. It is therefore important that all the parties identified engage fully and meaningfully at all stages. It is important that issues are widely understood at the earliest opportunity and that there is clarity on why differences remain, if they do.

Applicants should begin engagement and consultation early to allow time for parties to understand how the proposed development would affect them and how they can influence. Consultation and engagement are discussed further, later in this advice.

This advice should be read in conjunction with other advice as referenced and linked below. Parties should treat the advice given in a way that is proportionate to the size, complexity and contentiousness of the proposed development.

Pre-application advice

Applicants should engage with the Inspectorate regarding the matters set out below at an early stage during the development of the project, as set out in the 2024 Pre-application Prospectus. The aim is to enable production of well-prepared applications which can then proceed through an efficient examination. See Guidance on the pre-application stage for Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects.

Pre-application statutory and non-statutory consultations should be used to help applicants identify and resolve issues at the earliest stage and reduce the overall risk to the project and to examination time. All APs and IPs are urged to support early collaboration because linear projects give rise to many parties with whom applicants need to engage.

Environmental impact assessment and Environmental Statements

General advice on environmental matters is available on the Inspectorate’s Environment Advice Pages. In preparing Environmental Statements (ES) for linear projects, applicants should ensure that the accumulation of adverse or beneficial effects are reported not only ES geographic section by section, but also across ES section boundaries and across the project as a whole. The ES assessments should inform good design. The section on Environmental Impact Assessment and Good Design in the Planning Inspectorate’s advice on Good Design has more detail on how environmental impact assessment (EIA) informs good design.

Proposed development: what and where

On a linear project many IPs and APs will have specific interest in the part of the proposed development closest to them or affecting them locally. It is helpful to everyone if fundamental elements which would be established by the nature of the proposed development are set out up front. For example, where the start and end points must connect to existing connection points or where the technology must align with existing infrastructure. It makes best use of everyone’s time if these issues are clearly set out in a single place.

All parties need to be able to familiarise themselves easily with the purpose and outcomes of the proposed development. Applicants must draw together information in one source such as in a Design Approach Document (DAD) or Design and Access Statement (DAS). Such a document can signpost relevant information in other documents, such as a Planning Statement or an ES non-technical summary to avoid duplication. It is up to applicants to adopt a logical approach to their documentation.

Describe the proposed development, its design, purpose and outcomes

The Inspectorate’s Good Design Advice Page sets out the need for a transparent design process, which sets out outcomes and design principles.

It is particularly important for linear projects that the design process described addresses challenges and constraints and demonstrates the benefits. Linear projects may cause adverse effects in terms of severance and fragmentation without careful consideration at the earliest design stage of the interests of all parties. Where some elements of constraint are unavoidable, mitigation and enhancement options can minimise these effects and could create some beneficial outcomes. Therefore, it is essential this is explicitly considered.

Applicants should ensure that if they have identified opportunities outside the Order limits which will provide multiple beneficial outcomes that, these are included and, where feasible, secured through s106 or similar agreements. Only matters which have been evidenced and secured can be considered as potentially beneficial in assessing the overall balance of planning considerations.

In describing the proposed development, applicants should consider separating out the linear aspects such as underground cables, overhead electric lines and overground pipelines, from the non-linear elements such as substations, converter stations, cable sealing end compounds, non-linear pipeline above ground installations and block valve stations. Descriptions should clearly show where existing and proposed pipelines are above ground or underground. A definition for linear and non-linear is required if the terms are used in the DCO.

Applications should provide and illustrate geographic context and explain how the linear project connects with, for example, the national grid or wider pipeline systems. This is to help people unfamiliar with the type of project and location to understand the purpose, extent and connections of the proposed development.

It is helpful to include some of the plans and illustrations of the types referred to below in the section below on Plans, visualisations and illustrations, such as the plan for the Hynet Carbon Dioxide Pipeline.

Flexibility, detail and the Rochdale Envelope

The Rochdale Envelope approach is an accepted means used to assess the worst case scenario whilst maintaining flexibility to address uncertainty of the proposed development (including its mitigation). See also Content of a DCO for NSIPs.

Examples where flexibility might be sought include construction methods such as trenched or trenchless cable crossings. For linear elements it could include siting of apparatus such as link posts, vents and valves. For the non-linear elements it can include flexibility over footprint, height and massing of construction such as substations,

Flexibility is also secured through limits of deviation (LOD) and micro-siting, described below.

Limits of deviation

Because of their geographic extent and because precise construction techniques and ground conditions are unlikely to be known at application stage, linear projects will have lengthy and varied limits of deviation (LOD). It is standard practice to undertake micro-siting post-consent. (Micro-siting is the final technical and engineering design process by which the precise location of an infrastructure asset is fixed).

Applicants should set out clearly the reasons for required LOD. This should include any vertical (above and below ground) LOD sought, as well as horizontal LOD. Explanations where LOD need to widen along a linear route should be given. This may include futureproofing for increased size or capacity for example for a pipeline. Limits should be narrowed as far as possible. Further, location-specific narrowing of LOD to minimise adverse effects and interference with land rights should be explored and is encouraged. These modifications should be clearly set out on plan and explained.

Applicants should also ensure that the range of flexibility that is possible in practice within the maximum of the overarching LOD is clearly and simply set out for IPs and APs. For example, with an electric overhead line, if one pylon is finally positioned at one lateral extent of the LOD, rather than centrally, this would influence where adjacent pylons could be located to minimise direction changes.

Likewise, the flexibility arising from LOD on linear projects will often result in uncertainty regarding the extent of tree and hedge removal. Applicants should ensure that assumptions used to define such vegetation removal align with removal figures used in the EIA.

It can be helpful to illustrate tree removal on photographs or photomontages, such as this below from the Hinkley Point C Connection (HPCC).

A panoramic photomontage of a wooded area with tree groups circled in different colours indicating how much proposed tree removal would noticeably change the view.

Source: HPCC Supplementary photomontages showing tree removal

Order limits

Applicants need to explain and justify the proposed Order limits. In terms of justifying corridor widths, and associated powers sought it can be useful to provide cross-sections as for the Net Zero Project Teesside, which were submitted with the relevant Land plan, using different colours to illustrate the different powers.

A dimensioned cross section showing locations for pipelines, grassed areas and hardstanding.

Source: Net Zero Teesside Project Justification of Pipeline Widths

With linear projects there may be interactions with other NSIPs. Where these will occur, a plan showing how the application Order limits interface with those of any other NSIPs is required. The level of precision of this plan will depend on the stage reached of any other NSIPs and the extent of design detail being submitted in the application.

A masterplan of such an area of interaction can assist with placemaking. The Secretary of State amended the DCO to include such a strategic approach in their decision on Norfolk Boreas Offshore Wind farm (para 4.7.4 and 12.1.g.) because its substations were next to those of another offshore wind farm.

Applicants should make clear the status of other projects. It is also useful for applicants to include a note of how any made Order powers might be affected by the proposed DCO.

Evolution of design including alternatives

Design evolution narrative

Applicants should follow the recommendations and considerations set out in the Good Design Advice Page. For linear projects it is important that the narrative covers the construction stage as well as operation because of the potential to affect various communities and habitats along the route.

Optioneering and alternatives

Linear projects are likely to have followed an optioneering process to determine a preferred routeing. This requires a clearly structured approach, setting out criteria for selection and how the preferred route was determined. It should also link to design principles and cover any route section options. For some projects, alternatives that have been considered, but not chosen, by applicants are a point of disagreement with IPs and APs. Therefore, clear and thoroughly argued reasoning is essential.

It is advisable to discuss optioneering at pre-application meetings with the Inspectorate.

Whilst the detail of corridors and alignments considered is required, it is also helpful to include a summary of the process such as in the Bramford to Twinstead Planning Statement, section 5.7. In the case of overhead electric lines and their associated infrastructure, there are specific rules that NPS EN-5 states should be followed. They are Holford Rules for routeing and Holgate Rules for design and siting of substations. These may be subject to updating and the most recent equivalent version should be used.

The Infrastructure Planning (Environmental Impact Assessment Regulations (2017)) require applicants to demonstrate alternatives that they have considered, where they are reasonably available. Describing alternatives is also an important part of the process of good design. One example is that for undergrounding in the Bramford to Twinstead Planning Statement, section 5.7. Where alternative sites for non-linear elements have been considered these should also be explained.

The Inspectorate’s Advice on the pre-application stage provides information on the use of alternatives.

Options within DCOs

Flexibility for future commercial delivery alternatives or technological advancement can require options to be kept open at application and consent stages. Operational options within applications for linear projects can cover:

- routeing

- electrical current, high voltage alternating current (HVAC) or high voltage direct current (HVDC), which also influences the need for converter stations

Previously options have been left open for substation type which affects size and design, such as Awel y Môr Offshore Windfarm. This allowed for the installation of air insulated or gas insulated switchgear at the substation. The DCO set out different detailed design parameters for the two approaches.

There is not a single best way to handle options in DCOs. It will be dependent on the particular circumstances. The aim must be to use that which will give most clarity post consent for approvals and implementation. Any options included in an application will result in more examination (and possibly recommendation) time because all options will need to be considered equally against the relevant tests. Therefore, applicants should discuss the way in which options might be accommodated in their DCOs during pre-application with the Inspectorate.

Flexibility

Flexibility can also be required in terms of the level of detail which is provided prior to consent being granted. In principle this is an accepted industry measure. However, the more flexibility that is required, the more issues that should be resolved prior to application. Where flexibility is sought, the basis on which future post-consent approvals would be based must be secured. This could be during construction stage and operation stage. Worst case scenarios must be assessed. The information must be clear for IPs and APs who would be affected to understand what it means for them. The authorities signing off post-consent approvals must have a secured, clear approach on which to make future decisions.

DCO drafting which includes options

Examples include:

- Hinkley Point C Connection which had two versions of the DCO depending on whether route option A or B went ahead

- Norfolk Boreas Offshore Windfarm (OWF) contained optionality within one DCO for whether it would be developed alone or alongside another OWF

- Hornsea Project Three left the decision over HVAC or HVDC or a combination of both, to be made post-consent by the undertaker. Works for both were contained in the DCO, including a requirement to explain the choice to the relevant planning authority. The application included a diagrammatic cross section to illustrate the differences, shown below

Two diagrammatic sections (one for HVDC and one for HVAC) showing components of an offshore windfarm from a wind generating turbine in the sea to a substation on land.

Source: Hornsea Project Three ES Non-technical Summary

Change requests

Applicants should endeavour to resolve matters prior to submitting an application and to avoid change requests. This is particularly important because of the extent of land covered and the potential for affecting multiple areas.

Digital techniques and Artificial Intelligence (AI)

The linear infrastructure planning panel is developing good practice in the use of new technologies like AI in the planning of the major infrastructure critical for achieving national goals such as net zero, resilience and nature recovery. The Planning Inspectorate has published advice on the use of AI in applications and appeals. The use of AI is permitted but must be declared with the application and it is the responsibility of the applicant to ensure that it complies with relevant legislation and is fit for the purpose being used.

Construction stage

Phasing and timing of construction works

Linear projects may require lengthy, phased construction periods over long distances. Construction works may be planned to take place in several places at the same time along a route. Proposed outline construction programmes must be included in applications for all projects, based on best available information. For linear projects detail of phasing of stages should be provided, so that the duration and timing of the works on affected communities can be understood. Also, so that local authorities can understand and plan for any post-consent approval implications.

Yorkshire Green Energy Enablement Project’s (Yorkshire GREEN) applicant provided an example for post-consent stages in its response to a DCO issue specific hearing, Appendix E Template Structure of a Written Scheme of Stages.

Linear projects by their nature will involve interactions such as pipeline or cable crossings and with other construction projects. This can apply to linear and non-linear elements, such as co-located onshore substations for offshore wind farms. Joint working, such as sharing access routes or works areas can minimise adverse effects. This should be designed in and accommodated to minimise cumulative effects, where practicable, without needing to place reliance on another project.

Good Neighbour agreements are encouraged. One such example is the shared corridor approach as set out in the Cottam Solar Project Joint Report on Interrelationships between NSIPs. This explains that mechanisms have been introduced to all submitted DCOs to enable a shared grid connection corridor on behalf of four developers. Shared cable corridors were also secured for offshore wind farms with adjacent connections: Norfolk Vanguard with Norfolk Boreas and East Anglia ONE with East Anglia THREE. It is not sufficient just to state that a shared corridor would be established. The timing of construction activities from different projects using the corridor would be relevant to effects on receptors in the area.

If working hours are a matter of disagreement on linear projects, consideration should be given in the application as to whether there are different circumstances or receptors geographically which might lead to different working hours along different sections of the route. If this is the case, the reasons and locations for different working hours should be set out.

Construction access

Linear projects will require construction accesses over long distances (and are likely to require operational accesses for maintenance). Applicants are encouraged to discuss their reasoning for their construction access strategic approach to haul route, multiple access or a combination of both with the Inspectorate at an early stage. Applicants should also respond to APs’ and IPs’ concerns and where feasible continue to work on alternatives.

For example, a short section of haul route in an otherwise multiple access approach could bypass streets for an affected community. Likewise, the locations of access points need detailed consideration and can benefit from local knowledge, which can result in alternative locations or routeings.

Cut and fill balance

Where a need to import fill or export surplus material at geographically distinct sites along a linear route is identified, applicants should in the first instance consider localised landform options at sections or sites within the overall length to meet NPS requirements for a sustainable approach. If route-wide movement of material is needed it should be assessed in terms of CO2 emissions from vehicular movements and disturbance and multiple handling of soils. Where there is material suitable for reuse within the project length this should be utilised for ground modelling as part of the design approach to minimise waste or underused materials. For example, the Lower Thames Crossing application identified elements of excavated material proposed for use in the design of the portal approaches and a new Chalk Park which minimises internal transport and waste.

Site construction compounds, works areas and laydown area

Linear projects are likely to require a series of construction compounds, works areas, drilling areas and laydown areas along their route. Clarity on what activities would take place in which areas should be provided in applications and secured in the DCO. The extent of land required and the length of time for which it is needed should be set out.

This may require applicants to explain the construction approach, for example, the need for separate compounds for contractors constructing linear and non-linear elements of a project. Applicants should justify such locations and their Order limits in applications.

Whilst fixed locations should always be the preference, sometimes flexibility is needed for the final location of temporary construction compounds. If so, a process must be secured for post-consent approval, which includes location, detailed mapping, description and assessment on a worst-case basis in relation to sensitive receptors.

Construction stage effects and beneficial operational outcomes

Health and wellbeing of local communities

The construction of linear projects will interact with different communities along the route (and outside the route) in different ways. Applicants should ensure that the health and wellbeing of communities affected by construction are assessed in the EIA. Such an assessment will need to combine adverse effects assessed and reported elsewhere in the ES and should also bring in effects of severance, on roads and public rights of way (PROW). It should include communities outside the Order limits, where they are affected, such as by traffic.

One approach for bringing together all the topics that can affect local communities can be found in the Southampton to London Pipeline Project ES Chapter 13 People and Communities.

There will also be opportunities for communities along a linear route to benefit in different ways. Applicants should consider the potential for creating operational stage health and social benefits for people. These should be based on an understanding of local people’s aspirations and needs and the local environment. Thames Tideway Tunnel (Tideway) will provide seven new mini parks, all with unique features to reflect the local areas and their heritage. Putney Embankment Foreshore, an open space just west of Putney Bridge was the first to be completed.

Four photographs from the opening of the riverside space at Putney Embankment, London, showing people gathered and views of seating, artwork and the University boat race start line with text inlaid in bronze.

Source Tideway

Public rights of way

Linear projects can involve numerous interfaces with PROWs. This may require temporary or permanent PROW diversions and closures. Applicants should ensure that the effects of severance are fully understood and that means of communicating information about closures and diversions to different user groups are provided and secured.

As set out in the National Networks NPS applicants must consider what opportunities there may be to improve access and connectivity when mitigating adverse effects on PROWs, National Trails and other access land. The Inspectorate would expect applicants to consider the potential to provide access improvement as an outcome, whatever the type of linear infrastructure.

These improvements should include consideration of linking into surrounding networks such as National Cycle Routes. There should be liaison with the relevant transport planning bodies to achieve such interconnections. The M25 Junction 28 DCO included Requirement 17 for the approval of a wider scheme or agreement of a non-motorised users’ route which comprised both land within the Order limits and within the applicant’s control, as well as routes controlled by Essex County Council and Transport for London.

Land rights

Engagement with affected persons

Linear projects are likely to include large numbers of landowners and their representatives and other persons with rights over land (referred to as affected persons (AP)). There will also be a large volume of plots of a highly distributed nature. Both applicants and APs should recognise that the time for consultation on routeing and to make changes is during pre-application. Because of the large numbers involved, applicants and APs should engage early with the aim of reaching agreement before the application is submitted.

Therefore, applicants will be expected to have used a Land Rights tracker (which should be discussed with the Inspectorate during pre-application) in addition to the Book of Reference (BOR). A suitable template will be issued to you as part of the pre-application service. Depending on the scale and complexity of land rights being requested this may be in a short or longer form suitable for the examination. It provides searchable information about issues and progress, plot-by-plot and is needed because of the number of APs and plots involved. Applicants are encouraged to discuss the content and frequency of update of the tracker with the Inspectorate during pre-application meetings, such that it is proportionate for the complexity of project. The intention is for the tracker to be a tool which draws from data already held by applicants, presented to inform all parties of land rights negotiations and to assist ExAs.

Micro-siting

LODs allow for construction stage micro-siting, which is necessary when detailed ground and environmental conditions are unknown. This generally gives contractors the flexibility that they need. On occasion it can be appropriate and proportionate to allow for landowner consultation on site prior to construction, such as on the Yorkshire GREEN project in the Code of Construction Practice, para 2.2.14 and 2.2.15.

Crossing or affecting Statutory Undertakers’ land or apparatus

Linear projects are likely to comprise multiple cases of interface and crossings of land and apparatus where other Statutory Undertakers (SU) have rights and assets. It is usual that provisions to protect the rights of those SUs are included in the DCO.

As set out under Protective Provisions in Content of a DCO for NSIPs applicants should engage with affected SUs at an early stage. There is now also a clear expectation from the Inspectorate that SUs should engage constructively and early with applicants. This is important on linear projects because of the number of potential utility crossings or diversions and the range of parties involved.

Where bespoke provisions are required for the benefit of a particular SU, these should be included in the application DCO. Blank provisions in a draft DCO will not be accepted given the range of made DCO provisions already available. The aim should always be for agreed Protective Provisions to be confirmed in the application DCO. This is because it will save examination time through written questions and at hearings, when required.

The nature of the interfaces with each SU should be explained in the application. Where SUs disagree with applicants’ drafting, they should work with applicants to provide alternative wording, suitably drafted to align with the application DCO, ready for ExAs to consider for inclusion. The Land Rights Tracker should be updated to reflect progress.

Plans, illustrations and visualisations

There is a difference between:

-

plans that will be secured by the DCO and used for construction, those supporting the ES, which generally are certified and those required by the Infrastructure Planning (Applications: Prescribed Forms and Procedure) Regulations 2009 (as amended) (APFP Regulations) and

-

plans and illustrations to assist understanding of the proposals

There is a role for both to be included in applications and for consultation.

For plans secured by the DCO, supporting the ES and prescribed in the AFPS Regulations, in addition to Advice on the Preparation and Submission of Application Documents applicants should note the following:

-

plans of linear elements should consistently run north to south or west to east, to ease sequential reading of plans on-line

-

where practicable plans should be presented at the same scale, with the same section and sheet numbers for specific locations, to ease cross-referencing

-

a set of plans which shows all LOD (for linear and non-linear elements) on the same set should be included in applications

-

the Land Plan plot numbering should follow a logical sequence across the length of the route

-

inclusion of some road names, such as those named in the ES on at least some of the works plans and ES plans (traffic and transport for example) assists IPs and ExAs understand specific locations

-

inclusion on plans of identifying elements along a linear route, such as pylon numbers is recommended to help fix locations

-

the basis on which visualisations or photomontages have been drawn up should be clearly stated, such as where a most likely engineering scenario has been generated rather than a worst-case scenario

Applicants should be mindful of the benefits of using illustrative material in the application in terms of reducing time at hearings and the need for questions. There is also real benefit in using illustrative material in engagement and consultation for ease of understanding.

Examples of illustrative material which can assist follows below.

Schematic routeing representations

Such as the one below for the Hynet carbon dioxide pipeline.

A schematic map showing the routeing of pipelines.

Source: HyNet Carbon Dioxide Pipeline DCO, Planning Statement and Environmental Statement Non-technical Summary

Schematic sections

Different from the cross sections required under the AFPF Regulations (section 6(2)(b)) for highways and roads, schematic sections are for illustrative purposes to help explain the proposed development.

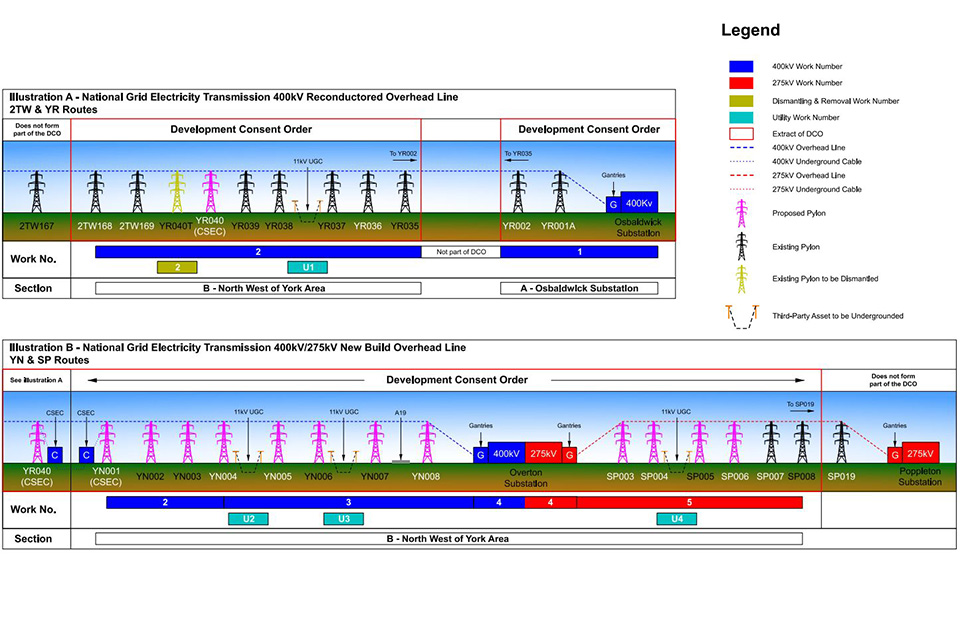

For example, the simple one for the Sheringham and Dudgeon Extension project and the more detailed one for the Yorkshire GREEN.

A diagrammatic section showing components of an offshore windfarm from a wind generating turbine in the sea to a substation on land.

Source: Sheringham Shoal and Dudgeon OWF Extension projects ES Non-technical Summary

Parts of a diagrammatic section showing different pylons coloured according to whether they are proposed, existing or for dismantling, voltages of lines, existing and proposed substations, and locations for undergrounding of third-party assets.

Source: Yorkshire GREEN Cross-section illustration of proposed works

Images of similar infrastructure

Such as an aerial view of a typical substation, as included in the Yorkshire GREEN Design and Access Statement.

An aerial view of a substation.

Source: Yorkshire GREEN Cross-section illustration of proposed works

Colour studies

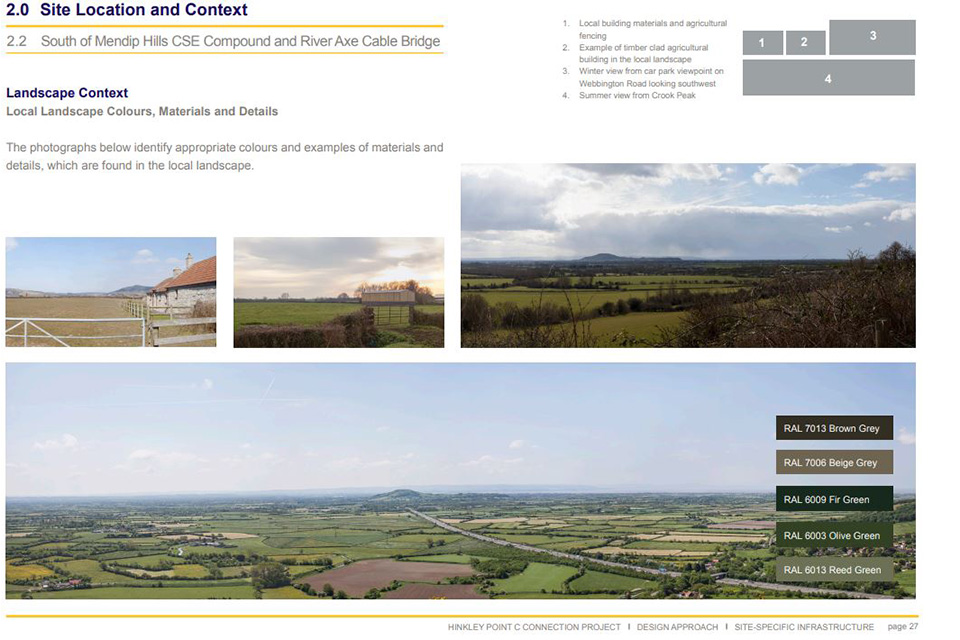

The Hinkley Point C Connection Design Approach for Site Specific Infrastructure document illustrates this. Whilst it may be premature to fix colours during pre-application and examination, contextual studies which lead to securing colour palettes can help during consultation and set out intentions for post-consent approvals. These are helpful where landscape or townscape character changes along a route.

A series of photographs showing different views of the South Mendip Hills that demonstrate the colours and materials within the local landscape with the proposed colour palette.

Source Hinkley Point C Connection Design Approach to Site Specific Infrastructure

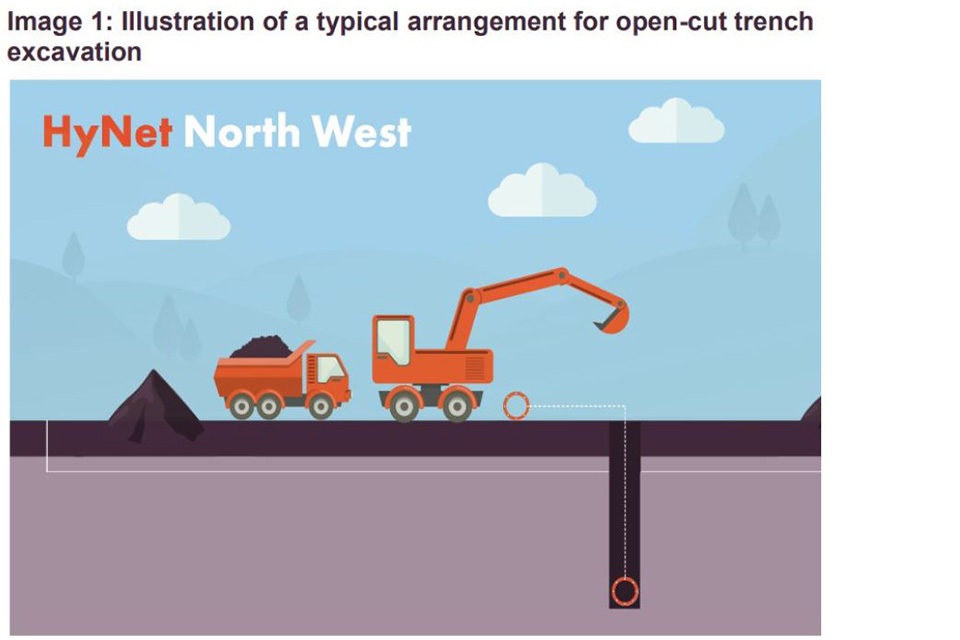

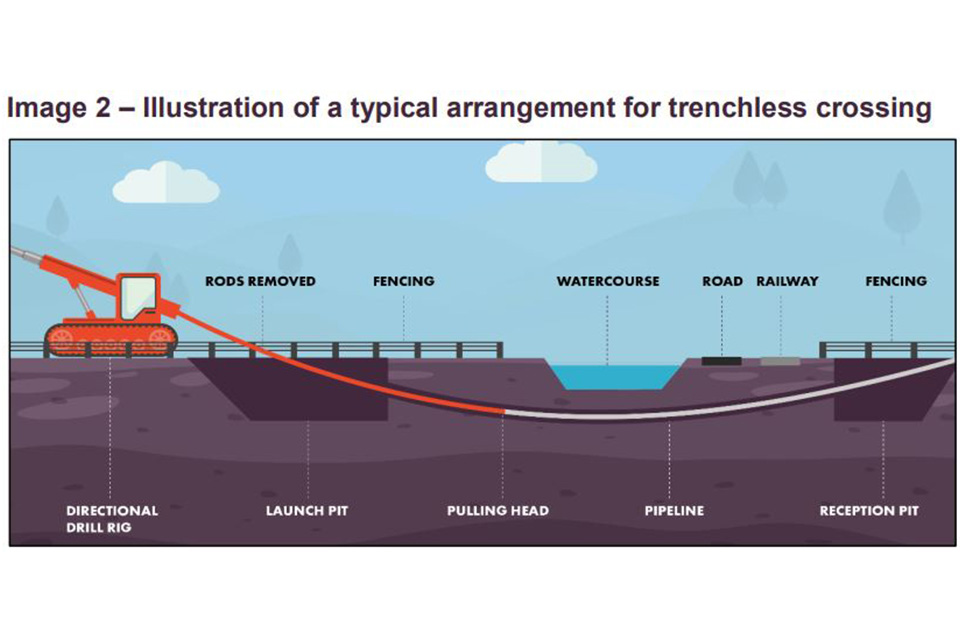

Diagrams to illustrate construction techniques

Such as those illustrating the difference between open-cut trench excavation and trenchless crossings for the Hynet Carbon dioxide pipeline.

A diagrammatic cross section showing construction of an open cut trench to bury a cable.

A diagrammatic cross-section to show horizontal direct drilling (HDD) to construct a cable under a watercourse.

Source: Hynet Carbon Dioxide Pipeline, Environmental Statement Non-technical Summary

Site-specific composite overlay plans

Along a linear route there may be locations where there are a complex range of activities being undertaken in a limited, specific location. A composite overlay plan can assist understanding in areas along a route such as that submitted as a Deadline 2 response from the Applicant on the Yorkshire GREEN Project (Appendix A).

Another example would be where overlapping designations or sensitive receptors occur at a particular location. Plans which set out the qualities and sensitivities of that site with mitigation and compensation proposals, including construction techniques can be helpful.

The ability for ExAs and IPs to interrogate GIS layers electronically would be another way of achieving a full understanding of the interactions between information on the different layers. However, it would be necessary to ensure the same information could be displayed in plan form for IPs who did not have GIS capability.

Indicative timelines

Such as that from the Norfolk Boreas OWF ES Non-technical Summary

Physical models

Physical models can be a useful tool for consultation purposes. They can be brought to hearings where relevant. The increased development of 3-D printing makes use of physical models for component parts of schemes increasingly more feasible.

Planning site inspections

Another way that applicants can assist ExAs is to provide locations of interest and possible route planning for ExAs to undertake unaccompanied site inspections on publicly accessible land during the pre-examination period. The longer the linear project, the more important this is. Likewise, it is useful if IPs and APs mention in their RRs, the places they want ExAs to visit. This is different from a request which may come later regarding accompanied site inspections, which are generally on private land.

Development Consent Orders

General information about the preparation of DCOs can be found in the Guidance by MHCLG and in our Advice Pages. Points which need particular attention on linear projects because of the geography, timescales and number of parties involved are:

-

secured documents which clearly set out the agreed intent for future post-consent approval for all matters where flexibility is retained in the DCO. This may include a Construction Environmental Management Plan, Code of Construction Practice (or similar) for construction stage and parameter plans, management plans and design approach documents. This should also include a secured ‘plan of plans’ which explains the relationships between construction stage plans and outline plans

-

clarity on what and how construction stage communication (such as over construction effects, access, PROW closures) will be available for local people because the linear nature means that work may be progressing in different areas concurrently over a long time period

-

clarity on what a construction ‘stage’ is (temporal or geographical) to assist those authorities involved in post-consent approvals. In most linear projects a staged approach to construction is planned and referred to in DCOs

-

clarity about the location, period of use and method of reinstatement of all temporary construction access points and tracks, including the likelihood of returning to re-use those for which permanent rights are sought

-

where an assessment assumes the use of a non-trenched crossing, this should be identified and secured in the dDCO and associated control documents

-

reaching agreement as far as possible on Discharge of Requirements Schedules because there may be many authorities involved

-

applications must contain a complete set of Protective Provisions (PPs). Where these have not already been agreed with the relevant parties the Land Rights Tracker should make clear their status and origin if previously made PPs are utilised

Engagement and consultation

Applicants, IPs (including local authorities and statutory consultees), APs (including SUs) and local communities all have roles to play during the pre-application stage. The Inspectorate expects that all parties will make reasonable effort to engage early and reach resolution, or if not to set out clearly where and why differences still exist. This is particularly important on linear projects because of the number of parties with which applicants need to engage and because of the extensive and varied geography which can give rise to different environmental, economic and social effects.

The geography of linear projects means that the proposed development may cross borders of different kinds. It is important to have clarity about the different parties and where joint working will apply. Applicants and all parties should note the Advice on the consultation report page on the Inspectorate web site.

There is a likelihood that the proposed development will pass through more than one local authority area. It is important to clarify whether local authorities will engage and respond jointly or individually. For the Hinkley Point C Connection Project, as described in the ExA’s recommendation (para 3.12.2) six local authorities organised themselves as the Joint Councils. They submitted a joint Local Impact Report (LIR) and were represented by Counsel at hearings as the Joint Councils. The Inspectorate deems this good practice as it enabled efficient examination. The Inspectorate encourages joint working where feasible. However, it is acknowledged that it is not always possible, for example on the Yorkshire GREEN Project, local government reorganisation took place during the examination.

Local authorities that plan to work jointly should ensure that the necessary delegations are in place during pre-application to enable them to work together on items such as Relevant Representations (RR), LIRs, Written Representations (WR), Statements of Common Ground (SOCG) and Principal Areas of Disagreement Summary Statement (PADSS). On some cases local authorities working jointly have planned resources so that different local authorities provide leadership for different technical areas on behalf of all authorities. This can enhance efficiency during examination. Local authorities should ensure that they have the technical resources necessary to engage during the pre-application period.

Where multiple local authorities will be responsible for post-consent approvals, it helps if they can align as far as possible on principles such as construction hours, timescales for discharge of requirements and other requirements.

Linear projects can cross national borders, such as Hynet Carbon Dioxide Pipeline. Applicants should ensure that the different policy frameworks are explained.

SUs are expected to engage early with applicants. The geography of a linear route means that there could be multiple operators. Where this is the case, SUs should clarify if they will represent themselves jointly or individually during the pre-application stage, so that it is clear in RRs and in the application draft DCO. For example, in Yorkshire GREEN’s made DCO, Northern Powergrid (Northeast) PLC and Northern Powergrid PLC (Yorkshire) were aligned under the abbreviation NPG for the purposes of the benefit of the Order and for Protective Provisions. Although this was not clear at the time of the application.

Similarly, although not SUs, Internal Drainage Boards (IDB) may wish to align themselves with other IDBs to engage with applicants during pre-application. ExAs find it expedient if there are joint submissions, where feasible. It is most helpful if this can be from the outset in RRs, WRs and SOCGs.

Direct and wide community engagement should take place. It should be instigated early by applicants. However, it may need to vary between groups that have opinions on route-wide aspects of the proposed development and those which are interested in specific effects in certain locations.

Local authorities should assist the applicant in identifying locations where engagement will be needed. It is helpful to ExAs planning unaccompanied site inspections after acceptance, during pre- examination, if locations where there is particular community interest can be identified. This could be in a DAS.

There are likely to be many landowners and those with an interest in land that may be affected. The Inspectorate emphasises, as stated above, the importance of both applicants and APs engaging and negotiating with each other at the earliest opportunity and where possible reaching agreement before the application is submitted.

Concluding points

The characteristic feature of a linear project is its geographic extent which will often engage a wide range of environmental and technical matters. It is important that their scale and impacts are understood and appropriately considered both locally and across the whole project. Applicants should follow the recommendations outlined in this advice note and related advice to help constructive understanding and engagement. All parties should engage early as this will assist in good design and effect consideration of the project.

Updates to this page

-

Added translation

-

Added translation

-

Welsh translation added

-

First published.