Viral haemorrhagic fevers: origins, reservoirs, transmission and guidelines

Examples of viral haemorrhagic fevers (VHFs) include Lassa fever, Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever, Marburg and Ebola virus diseases.

Viral haemorrhagic fevers are a group of illnesses caused by several distinct families of viruses: arenaviruses, filoviruses, bunyaviruses and flaviviruses.

Some of these cause relatively mild illnesses, whilst others can cause severe, life-threatening disease; some are high consequence infectious diseases (HCIDs).

The viruses depend on their animal hosts for survival, so they are usually restricted to the geographical area inhabited by those animals.

The viruses are endemic in areas of Africa, South America and Asia, with some present in parts of Europe.

Arenaviruses

Known arenaviruses include:

-

Lassa virus: the cause of Lassa fever, endemic in parts of west Africa

-

Lujo virus: a novel virus that caused a small outbreak in South Africa following transmission in Zambia in 2008

-

Junin virus: cause of Argentinian haemorrhagic fever

-

Guanarito virus: cause of Venezuelan haemorrhagic fever

-

Machupo virus: a cause of Bolivian haemorrhagic fever

-

Chapare virus: a cause Bolivian haemorrhagic fever

-

Sabia virus: cause of Brazilian haemorrhagic fever

The South American Arenaviruses are very rare causes of infection in travellers.

Read more about South American Arenaviruses.

Filoviruses

Known filoviruses include:

Bunyaviruses

Known bunyaviruses include:

-

Hantaviruses, which cause haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome and Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome

-

Rift Valley fever virus, which causes Rift Valley fever

Flaviviruses

Known flaviruses include:

- Alkhurma virus (Saudi Arabia)

- dengue virus: the cause of dengue haemorrhagic fever and dengue fever

- Kyasanur Forest virus (India, Karnataka State)

- Omsk virus (Siberia)

- yellow fever virus: the cause of yellow fever

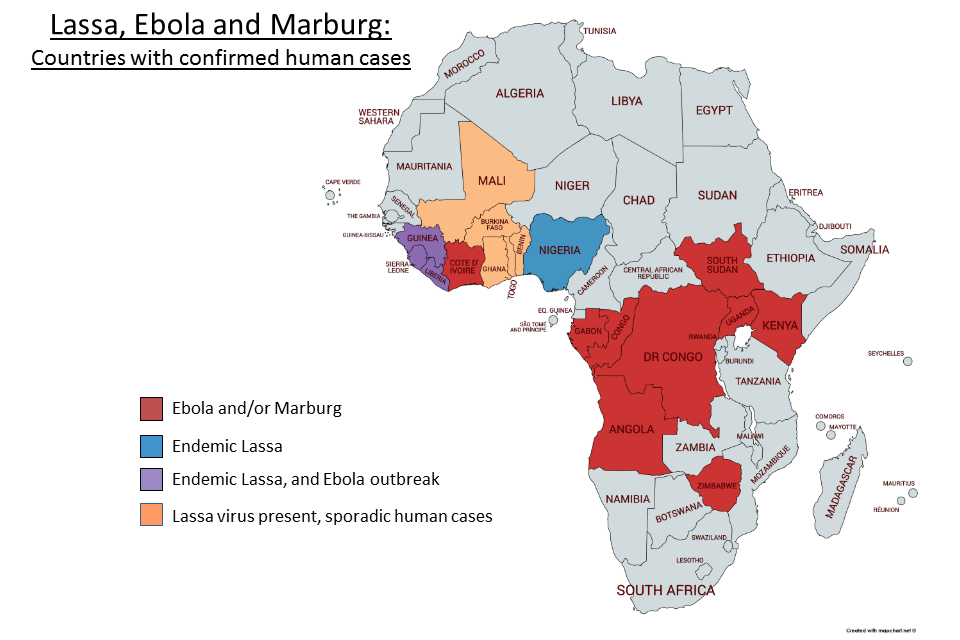

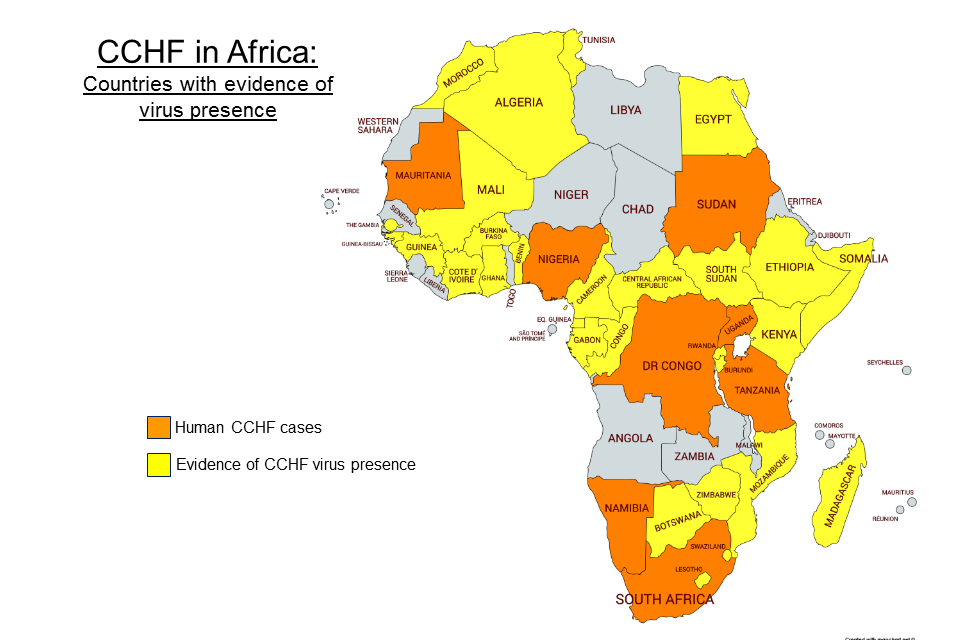

Epidemiology and maps

The viruses depend on their animal hosts for survival. They are usually restricted to the geographical area inhabited by those animals, or a specific arthropod vector. The viruses are endemic in areas of Africa, South America and Asia.

VHF risk by country is included in the HCID country specific risk listing.

WHO map showing global CCHF distribution

Human cases or outbreaks of viral haemorrhagic fever occur sporadically and irregularly, and are hard to predict.

Occasionally, humans may acquire infection from animal hosts that have been exported from their native habitats, as occurred when laboratory workers in Germany handled imported monkeys infected with Marburg virus.

Environmental conditions in England and Wales do not support the natural reservoirs of infection.

Transmission

Humans are not the natural host for these viruses which normally live in wild animals.

Rodents are the main reservoirs of many haemorrhagic fever viruses. Examples include the multi-mammate rat, cotton rat and house mouse.

Humans may acquire infection when they come into close contact with:

- live animal hosts

- animal carcasses during slaughtering

- animal droppings

Tick or mosquito bites can transmit some of the viruses, such as yellow and Crimean-Congo fever, between animal species, including humans. For other viruses animals are the host.

Lassa, Ebola, Marburg and Crimean-Congo viruses can spread from person to person through close contact with symptomatic patients or contaminated body fluids.

Symptoms

The incubation period varies according to the type of virus, but is rarely longer than 21 days.

Symptoms also vary according to the type of virus, but initially they generally include:

- fever

- fatigue

- dizziness

- muscle aches

- weakness

In early stages, symptoms may resemble other infections such as malaria or typhoid fever.

Patients with severe disease may show signs of bleeding under the skin, from body orifices like the mouth, eyes and ears, or into internal organs. Severely ill patients may also show signs of shock, kidney failure and nervous system malfunction including coma, delirium and seizures.

Diagnosis

Laboratory tests in a specialist PHE laboratory, the Rare and Imported Pathogens Laboratory (RIPL), including antigen and antibody detection, can diagnose VHFs definitively. Antigen detection is particularly useful in the early acute stage of illness.

Treatment

Some viral haemorrhagic fevers, such as Lassa fever, are treatable with anti-viral drugs. Most, however are only managed supportively.

New drug therapies are being evaluated for Ebola virus disease.

Guidelines

The UK has specialist guidance on the management (including infection control) of patients with viral haemorrhagic fever. It provides advice on how patients suspected of being infected with a VHF should be comprehensively assessed, rapidly diagnosed and safely managed within the NHS, to ensure the protection of public health.

Prevention

A vaccine is available to protect against yellow fever, and is recommended for travellers to endemic areas.

No licensed vaccines are available against other types of haemorrhagic fever viruses. Therefore prevention measures concentrate on avoiding contact with host species or with people known to have the disease.

Because many of the hosts that carry haemorrhagic fever viruses are rodents, disease prevention efforts in endemic areas include controlling rodent populations and keeping rodents away from homes and workplaces.

For haemorrhagic fever viruses spread by vectors, prevention measures also include controlling the population of ticks and mosquitoes, and preventing bites by wearing suitable clothing and repellent spray, and using screens or nets.

For haemorrhagic fever viruses that can be transmitted from person-to-person, great care needs to be taken when nursing patients, including isolation and the wearing of gloves, gowns and masks, in order to prevent the spread of infection. See ACDP algorithm and guidance on management of patients.

Viral haemorrhagic fevers in the UK

Environmental conditions in England and Wales do not support the natural reservoirs of infection, thus cases do not occur here except as an imported disease. Such imported cases in travellers returning from endemic areas are rare. There have been:

- 8 cases of Lassa fever since 1980

- 2 confirmed cases of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever (1 in 2012 and 1 in 2014)

- 1 case of Ebola virus disease in a healthcare worker who had been working in Sierra Leone during the West Africa outbreak (2 other Ebola cases were medically evacuated to the UK after diagnosis in Sierra Leone)

Further information

New World Arenaviruses factsheet

WHO Yellow fever

Updates to this page

Published 5 September 2014Last updated 12 October 2018 + show all updates

-

Updated page with epidemiological maps.

-

Updated the VHFs in Africa map.

-

The Viral haemorrhagic fevers in Africa: areas of known risk map has been updated.

-

Updated 'Viral haemorrhagic fevers in Africa: areas of known risk map (JPG image)'.

-

First published.